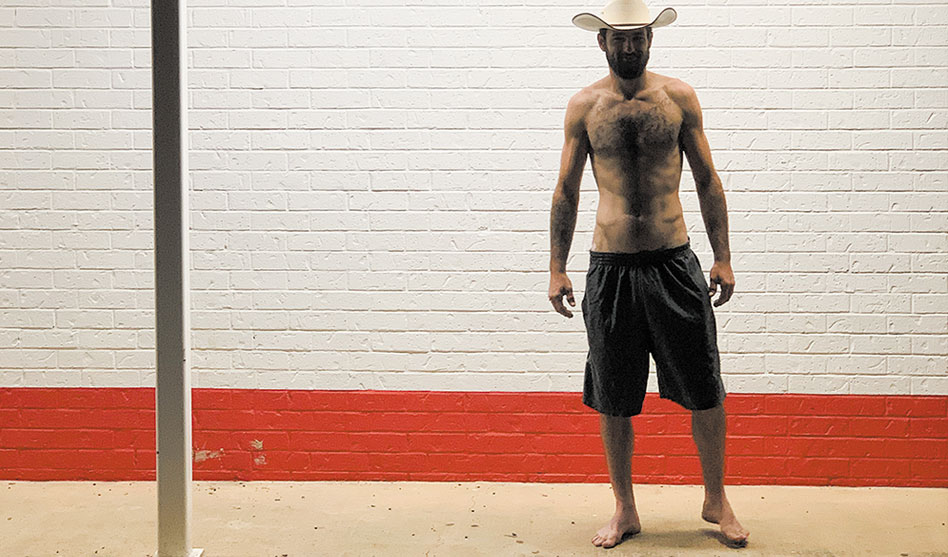

Cole in blossom, night, 2020

From bullies to muses, East Texas artist empathizes with his subjects

JAMES RUSSELL | Contributing Writer

James.Journo@gmail.com

Chivas Clem returned to his hometown of Paris, Texas, in 2010 after more than a decade in New York City, to find the small town he left in the late 1980s to attend Connecticut College mostly unchanged. He also found new inspiration from an old, unexpected source.

Cole with dead hawk 2021

When he first got to New York, Clem was selected to study in the prestigious Whitney Independent Study Program at the Whitney Museum of American Art. It is a selective program that has produced internationally-renowned artists, critics and curators.

Clem studied in the visual arts division. But he worked across fields, including at magazines and running an acclaimed art space. He found some success, but by the time he moved back home to Texas, he had grown sick of the hustle of the art world.

Plus, in Paris, he realized, he could live “comfortably on nothing.”

Among the people he stayed in touch with is curator Alison M. Gingeras, who curated his newest show — Shirttail Kin — which opened at the Dallas Contemporary on Oct. 17 and runs through Jan. 12, 2025. The exhibit includes more than 70 photographs, spanning a decade, of men — roughnecks, rednecks, homeless, illiterates and ex-cons — who have been stereotyped and demeaned in public life. To others, they were the angry white men who former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton described during her 2016 presidential campaign as “deplorables.”

But for Clem, they are guys in his community and part of the “shirttail kin,” a Southern term for chosen families.

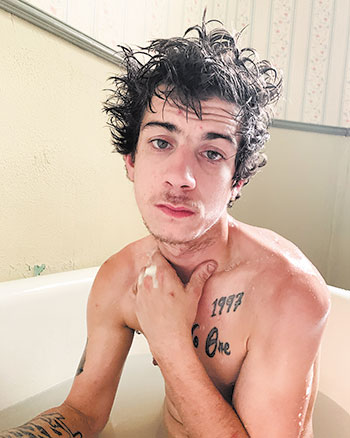

Coty in the bathtub after breaking in, 2021

“It’s terrible to call anyone that,” he said of Clinton’s moniker for these men and those like them. Yet he was curious:

What does a so-called “deplorable” look like. Do they look like these men? And are these transients like the guys who bullied him for his sexual orientation as a young man?

For the next decade he developed relationships with these men, some of whom were in and out of prison. They became his “shirttail kin” — a southern term for one’s chosen family.

“I was making sculptures and needed studio assistants,” he said. “They wouldn’t move things. They’d break things. They were terrible studio assistants.”

But even so, Clem realized, these men were human, too. He began photographing them, sometimes in provocative positions. Eventually, he amassed 1,600 photographs of these guys shooting up drugs, lounging around naked, masturbating and just staring aimlessly.

In some photos they’re naked, revealing mostly slender, tattooed bodies — not the bodies of “deplorables,” and no less the perception of the Southern man.

With this show, Clem shows off this series for the first time. The photographs take a different direction from Clem’s previous works, which dealt with celebrity culture and subculture niches. Thematically, it is a good fit for Gingeras, a curator with an incredible attention to detail, understanding of the significance of space and a wide variety of interests.

“He’s moved from the fragility and hypocrisy of movie stars and their downfall. He has a real radar for emotion and empathy as well as the opposite,” Gingeras said of Shirttail Kin. “His work comes from an interesting and genuine perspective — an incredible reversal from being terrified of to now befriending the same type of person.

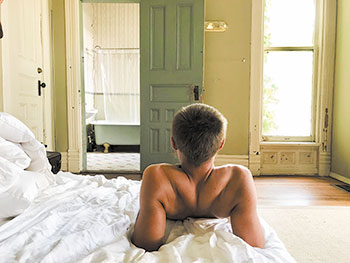

Drifter on my bed, 2018

“He’s created this muse relationship. There’s a depth of human connection in the images,” she added.

Despite past experiences with Southern masculinity, Clem realized these men weren’t those bullies. He could’ve approached them as the stereotypical Southern men who beat him up, but, he said, “I didn’t want to be afraid of them.”

And he wasn’t.

“I’ve been intertwined in their lives. Some have been to my parents’ home. Some call me in an emergency,” Clem said.

“All of these guys grew up having nothing, and they still don’t have anything. No one nurtured them. They’re this whole underclass created by social and political systems.”

But the commentary isn’t his point. His photographs are not about social justice and progress.

“I didn’t go in to lift them up,” he said. Nor did he want, even as a queer artist, to make these works a queer statement.

People are obsessed with whether the men are gay, yet none of them identify as gay.

“In the art world, this is identity work. My work gets coded as queer. But it’s much more complex,” Clem said. “There’s something interesting about letting me into their lives. It’s adjacent to queerness,” he said.

Clem is evading these stereotypes, said Gingeras. “He’s also showing how complex sexual identity is. Not many people are going there on this level.”

And the timing is intentional, she added.

“In an election year, we hear about this polarized rhetoric about the marginalized white man. This deconstructs the myth of the white men ‘who are left behind,’” she said.