Victoria Kirby York

Marginalized communities share similar histories and can make greater progress together

JAMES RUSSELL | Contributing Writer

james.journo@gmail.com

Victoria Kirby York remembers when Hillsborough County Board of Commissioners in Florida banned public recognition of LGBTQ Pride. The director of public policy and programs for the National Black Justice Coalition, a Washington, D.C.-based organization working on Black LGBTQ issues, also remembers when the county later repealed the ban.

York, who uses she and they pronouns, thought change was afoot.

Abel Gomez

Now, a decade later, Gov. Ron DeSantis, a hardline Republican who announced a presidential run, is doing his best to reverse that change.

He’s signed numerous culture war bills mimicked in other states. Among them is the so-called “Don’t Say Gay” law, restricting conversations about gender and sexuality in public schools.

“They’re now trying to erase LGBTQ history and even talking about families,” said York, who is married to a woman and has a five-year old. “Could my five-year-old still have conversations about her parents or relate to other teachers?”

Having these conversations at school can be affirming, York said, but “the erasure of our families suppresses these conversations.”

In 2022, DeSantis signed the Individual Freedom Act, commonly known as the Stop Wrongs to Our Kids and Employees Act — or the Stop WOKE Act — restricting discussions in public schools and workplaces about anti-discrimination efforts. York and others call it the

“Don’t Say Black” law.

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis is rolling back progress toward equality with his racist and anti-LGBTQ legislation

The 11th Court of Appeals blocked the law, however. U.S. District Judge Mark Walker described it as “positively dystopian.”

DeSantis hasn’t backed down. In another overtly racist move, DeSantis banned the College Board’s pilot program for an African American Studies Advanced Placement course. He, again, called it “woke” and lamented the inclusion of Black Queer theory and intersectionality in general.

The College Board watered down the curriculum, making teaching about Black Lives Matter, Black queer theory and other topics optional. That earned the ire of the NBJC and other civil rights organizations.

With such laws, students are less prepared for college and work life without having a safe forum to learn and discuss. “There’s no chance to wrestle with challenging conversations,” York said.

Reactionary legislation is just a way to dodge these difficult conversations, York said. That leads to misrepresentation of why critical examination of our history is important.

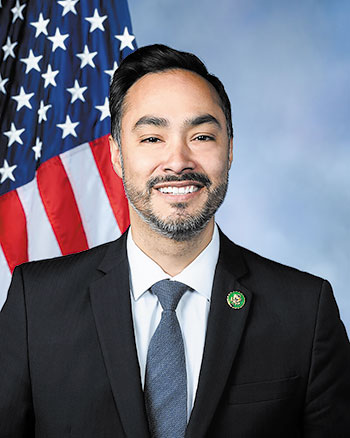

Joaquin Castro

In 2021, Congressman Joaquin Castro, a Democrat representing San Antonio, told the New Yorker that Latinos “have been left out of much of the telling of American history and our state histories, including in my home state of Texas. The only Latinos in this case, mostly

Mexican-Americans, that I remember — or Mexicans, actually — that I remember learning about were the defenders of the Alamo, and really not much else,” he said.

“Media — and particularly Hollywood, I think — is the main image-defining and narrative-creating institution in American society. In the way that it tells stories and whose stories get told and who it allows to be part of the storytelling, it affects how Americans see each other, including how Americans see Latinos and how we see ourselves and the numbers in terms of representation and portrayal of Latinos,” Castro said.

Just ask Abel Gomez, a queer Latinx assistant professor of religion at Texas Christian University specializing in gender and Native American and Indigenous studies.

“Students don’t learn about Indigenous history. We have to talk about Native people as cartoon characters,” Gomez said.

Castro argued the media is complicit in defining those tropes.

While queer movements want to include Two-Spirit and Native peoples in their movement, as seen through the white gaze, the term “Two-Spirit” is traditionally perceived as an umbrella term including LGBTQ people.

But even that’s a misconception.

Junípero-Serra,-the-first-saint-canonized-in-the-United-States,-led-the-enslavement-and-death-of-thousands-of-Native-people

According to the Indian Health Service, a bureau within the Department of Health and Human Services, “Two-Spirit” is an umbrella term referring to the varieties of people who may not prescribe to one of other genders. No two tribes share the same belief in the roles and acceptance of “Two-Spirit” peoples either.

Two-Spirit people have to contend with identities as queer Natives but are seen through the lens of colonizers. Scholar Randy Burns described the tension “double oppression.”

So, Gomez said, while mainstream queer movements think about race and ethnicity, missing from the conversation is a concept completely erased outside of mainstream movements: the legacy of colonialism.

Gomez was raised in the San Francisco Bay Area, where much of his research is focused. Central to the city’s built environment are the Spanish missions, including Mission San Francisco de Asís. It’s also commonly known as Mission Dolores for the nearby popular park for the queer community.

Gomez spent plenty of time in the park but was also rankled by the idea that the queer movement occupies a space with a dark history. Junípero Serra, who was the first saint canonized in the United States, founded the mission. He also led the enslavement and death of thousands of Native people, according to Elias Castillo’s 2016 book A Cross of Thorns: The Enslavement of California’s Indians by the Spanish Missions.

Like the rest of the United States, the park is on native land. And in Indigenous and Native communities, land, place and identity are intertwined.

So, the larger question for Gomez is, “How do we divest from these larger structures?”

York is a strategist with a mind for messaging. To make the case for inclusivity, she argues how Republicans’ push to limit open discussions harms even white, heterosexual cis men: “They could be unaware of how it could help them. Take, for example, an advertising executive who chooses a monkey shirt on a Black baby for an advertisement. Did he know it was offensive?” she asks.

That advertising executive could wind up losing his job and being dragged on the Internet, all because he didn’t know.

“Being culturally aware provides important context,” York said. With erasure, kids lose the opportunity to learn about great role models from 50 years ago, such as the gay Black civil rights activists Bayard Rustin and the Rev. Pauly Murray, who some scholars argue was transgender or gender nonbinary.

So, while communities of color have lead conversations about civil rights and liberation, Gomez said, “the faces of these movements are white.”

Instead of thinking about systemic issues as scary, addressing systemic issues, Gomez argues, “is in fact an opportunity to take an invitation to think about and be part of co-creating a different world.

“This is an invitation to all of us to be part of the process and look at things differently, for queer folks and other movements to think about a world where we all thrive,” he said.

Knowing things and waking them up to something unique is not new; “It’s history,” York said.