Yeah, The Hunger Games wraps up its arc this week. Big whoop. There are also smaller films opening this week, and while not all are impeccable, they offer more insights into the human condition than you’ll find in all of Panem.

Yeah, The Hunger Games wraps up its arc this week. Big whoop. There are also smaller films opening this week, and while not all are impeccable, they offer more insights into the human condition than you’ll find in all of Panem.

Somehow, American adaptations of films set in foreign countries often don’t fit right. Martin Scorsese won his only Oscar for directing The Departed, a dandy crime thriller adapted from the Hong Kong actioner Infernal Affairs, but despite the Boston setting, it still felt like someone else’s movie. The same director, George Sluizer, made both the American and original Dutch version of his film The Vanishing, but the changes to the remake felt tacked on — a betrayal of its source material. And it never seemed authentic.

Secret in their Eyes, the new adaptation of the Oscar-winning Argentine film El Secreto de sus Ojos, suffers from a similar fate. The original was a disturbing, violent portrayal of obsession; this version, while well-acted, feels false.

The broad strokes of both films are the same: In 2015, Ray (Chiwetel Ejiofor), a former FBI agent, thinks he has tracked down a man who disappeared 13 years earlier, the chief suspect in the murder of his then-partner Jess’s (Julia Roberts) daughter (seen through multiple flashbacks). The man slipped through the system before, and fell off the grid; Ray wants the new D.A. Claire (Nicole Kidman) to reopen the case, and bring justice and closure finally to Jess. But Ray’s return is tinged by the unrequited love between him and Claire.

There’s a lot going on in this movie, and while it felt artsy, even ethereal, in Spanish, now it just seems unfocused and overwrought. The system of flashbacks seems like it’s intended to add psychological layers, but comes off more as a shell-game — how much can we hide, and how sympathetic can we make the characters before you learn some truths about them? Ray, for instance, is a dogged cop, but as we soon learn, not a very good one. The script relies repeatedly on him flying off the handle, or doing shoddy police work. (How many times does he have to shout at the suspect from 30 feet away, “Hey! You!” before he thinks to sneak up on the guy instead?) Police procedurals are tricky in a culture weaned on Law & Order, and this one seems like it was written for a 1950s audience. (It’s also fraught with silly coincidences, cliches and functional characters that don’t feel real.) The PG-13 rating also softens much of the more dire and shocking aspects of the original. There’s less meat on the bones.

Even so, the acting is solid, especially from Roberts as a shaken, broken woman. There’s a hollowness in her eyes and her largely un-made-up face. When Ray says, “You look about a million years old,” you realize, yes, the Pretty Woman can play character parts, too. Too bad she’s not in a better movie.

If Secret is about seeking justice, Trumbo is about its perversion. During WWII, the U.S. and the Soviets were aligned; within a few years, however, the Cold War was heating up and the Communists who had once been our allies were now our enemies. That meant any American liberals who sided with Marxist philosophies (such socialistic ideas as The New Deal, collective bargaining and free speech) were labeled as undesirables, if not outright unpatriotic. A single instance of spying by Julius and Ethel Rosenberg painted everyone of their ilk as terrorists and enemies. (Sound familiar?) And some of the first tainted by the sobriquet “disloyal” were Hollywood liberals … especially the writers, who came up with the ideas and put them on the page.

If Secret is about seeking justice, Trumbo is about its perversion. During WWII, the U.S. and the Soviets were aligned; within a few years, however, the Cold War was heating up and the Communists who had once been our allies were now our enemies. That meant any American liberals who sided with Marxist philosophies (such socialistic ideas as The New Deal, collective bargaining and free speech) were labeled as undesirables, if not outright unpatriotic. A single instance of spying by Julius and Ethel Rosenberg painted everyone of their ilk as terrorists and enemies. (Sound familiar?) And some of the first tainted by the sobriquet “disloyal” were Hollywood liberals … especially the writers, who came up with the ideas and put them on the page.

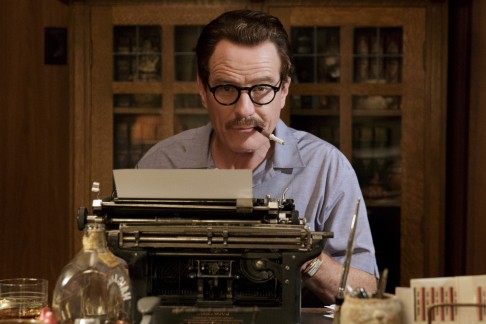

The blacklist (and the HUAC hearings that caused it) is one of the most shameful betrayals of American ideals of the 20th century. So tense was the political atmosphere that Americans and their leaders willingly turned on the First Amendment in favor of witch hunts. And the biggest target was slapped on the screenwriter Dalton Trumbo (Bryan Cranston). Trumbo was an outspoken Communist, an intellectual floating in a sea of morons. He was the studios’ highest-paid wordsmith, and seen as indispensable. He wasn’t. When he refused to “name names,” he was sent to prison and banned from writing for a decade. To pay the bills, he uses “fronts,” other, less controversial people who could sign their names to his screenplays and share the fees. He won two Oscars that way … though others’ names appeared on the statuettes.

The blacklist is an inherently cinematic and thrilling era to bring to life, so it’s a shame that Trumbo lacks the scope and ambition it needs to be great. It’s directed by Jay Roach, whose feature films are marked by the Austin Powers comedies but who has tackled politics in several well-received TV movies for HBO (Game Change, Recount). His style is more suited to the small screen than the big; everything about Trumbo seems pre-digested and safe — a perfectly adequate way to spend your Sunday watching television, but not bold enough to bring you to the theater.

Cranston is a star on the small screen, but blown up to 30 feet and carrying a film, he feels overly broad and one-dimensional. His Trumbo is confident to the point of smugness; the entire role reminds you of the haunting line from Anne Frank’s diary that people are essentially good, even as their most evil natures are about to destroy you. “Do you need to say everything like it’s going to be chiseled in a rock?” asks one of Trumbo’s frustrated colleagues (Louis C.K., who also shouldn’t be allowed free reign to act in features). Cranston just grins obliviously behind a cloud of smoke. (If they gave an award for Best Supporting Cigarette Holder, Trumbo would win.) The story is compelling, but the film never rises about predictable. Dalton Trumbo would never write a film as ho-hum as this one.

It’s time we all acknowledge that Angelina Jolie Pitt (as she’s now known) is a damn gifted filmmaker — probably better at writing and directing than acting. Her first feature, In the Land of Blood and Honey, was a gripping portrait of survival in the Bosnian War; her second, last year’s Unbroken (which she directed only) proved that women other than Kathryn Bigelow know how to tell a brutal story of war with smarts and understanding. She goes in an entirely new direction with By the Sea, a new chamber character study starring Jolie and her husband Brad Pitt. The style and setting is a woozy throwback to the artsy indie and European films of the 1960s and ’70s. Roland (Brad) is an acclaimed novelist looking for inspiration in a remote seaside village in France; his wife Vanessa (Angelina) is moody and remote. There’s something wrong with their relationship (we suspect an infidelity), but we can’t quite tell. They never talk about it.

Vanessa becomes obsessed with their neighbors in the hotel, two newlyweds whom she’s able to spy on through a hole in their common wall; she watches them have sex and argue. Eventually, Roland joins her, and their relationship seems reborn by their voyeurism. But everything has to end.

By the Sea has no chase scenes, no lurid sex (though a fair amount of nudity), no melodramatic excess (at least until the end, which doesn’t quite work). Instead, it’s a study not of people, but of a marriage. It revels in mood and style, like The Happy Ending or Rachel Rachel or The Heart is a Lonely Hunter; you could imagine Roman Polanski making it with Catherine Deneuve in a parallel universe.

I suspect, though, that many people won’t appreciate its retro qualities, its seamlessness or its thoughtful, leisurely pace, and merely look for insights in what it says about two movie stars married in real life; others will dismiss it as a vanity project for an actress who, admittedly, can often project a self-satisfied hautiness. That’s too bad. Taken on its own, By the Sea is a dreamy romantic drama, the kind nobody makes any more.

All films are now playing.