Although his years as leader of the largest LGBT church in the world weren’t without controversy, there’s no denying Michael Piazza has left a lasting impact on North Texas

Although his years as leader of the largest LGBT church in the world weren’t without controversy, there’s no denying Michael Piazza has left a lasting impact on North Texas

DAVID TAFFET | Staff Writer

taffet@dallasvoice.com

It’s not often that the Rev. Michael Piazza gets caught at a loss for words. But as he walked through Cathedral of Hope’s columbarium recently, he simply touched the marble covering the ashes of the late activist John Thomas, gently caressing the name plate without saying a thing.

Then he turned to the other memorial plaques, many of which originally hung on the outside wall of the old Metropolitan Community Church, the building that is now the Gay and Lesbian Community Center.

He pointed to one and asked if I knew him. We told each other stories about some of the people whose names hang there in remembrance. Most died of AIDS-related illnesses.

For Piazza — who is moving to Atlanta where he will take over as senior pastor of Virginia Highland Church on March 1 — leaving these people may be the hardest part of leaving Dallas. He worries that the memory of some of them will be lost.

Piazza knows Cathedral of Hope — the church known as Metropolitan Community Church of Dallas when he became senior pastor in 1987 — will be in good hands and he’s proud of the institution he helped to build.

But he still feels a great sadness at leaving behind the names in that memorial garden — the friends, church members, community leaders whose funerals he performed — at one point, as many as a dozen of them in a week.

Piazza served as senior pastor and then dean of Cathedral of Hope for 23 years. Currently, he is president of Hope for Peace & Justice and he co-founded and co-directs the Center for Progressive Renewal, an organization that trains leaders to build new and revitalize old churches within the United Church of Christ, the denomination Cathedral of Hope joined in 2006.

David Plunkett, Piazza’s assistant for the past nine years, was hired by Virginia Highlands Church to become director of church life. Last year, Plunkett moved from his position at Cathedral of Hope to become executive administrator for the Center for Progressive Renewal. He has served as Piazza’s principle proofreader for his last five books as well as most of his articles and sermons.

Piazza said that he couldn’t get his job done without Plunkett. But Plunkett downplayed his role and said he simply makes it appear that Piazza is in two places at the same time.

From Atlanta, Piazza will continue to co-direct the Center for Progressive Renewal. The Rev. Cameron Trimble, the other half of that team, is based there.

Piazza said that Trimble’s strength is creating new congregations while his is turning around declining congregations. Their goal is to spread the liberal UCC denomination, strongest in the northeast, across the south.

After a year of travel in his new position, Piazza said it became obvious that they needed a base of operations. Virginia Highlands, without a pastor for two years, provided that opportunity.

While his new church is large, its congregation has become quite small, something Piazza sees as a wonderful challenge.

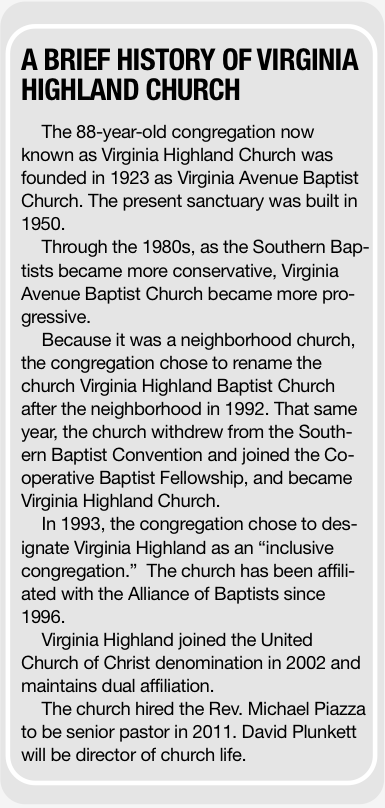

Founded in 1923 as Virginia Highland Baptist Church, the congregation designated itself an inclusive congregation in 1993, withdrew its membership from the Southern Baptist Convention, affiliated with the more liberal Cooperative Baptist Fellowship and then joined the Alliance of Baptists in 1996.

In 2002, while maintaining its Baptist affiliations, the church joined UCC.

Piazza admitted there was something quite delicious about becoming the pastor of a church that once belonged to the denomination that blocked Cathedral of Hope’s membership in the Greater Dallas Community of Churches.

While First Baptist Church of Dallas still publicly denounces homosexuality, it’s former pastor, W.A. Criswell, used to denounce Piazza personally and Cathedral of Hope in general by name from the pulpit.

That doesn’t happen anymore, Piazza said, and he counts that as part of his legacy.

Ask those outside the church about Piazza’s accomplishments and they’ll mention buildings — the original Cathedral, the John Thomas Bell Wall, the Interfaith Peace Chapel and the as-yet-unbuilt, Philip Johnson-designed, new Cathedral.

Ask those who’ve worked with him or have been longtime members and one word is repeated — vision.

Annette and Pat, who asked that their last names not be used, were on the board of the church when Piazza was hired and were the first couple in Dallas to meet him in person.

“We picked him up from the airport,” said Annette.

Piazza had flown in from Jacksonville where he was pastor of an MCC that he nurtured from 28 members to 270 in a short time.

“He was a visionary for the church,” Annette said. “He saw potential in us. He took worship to a different level.”

She said that as soon as Piazza got to Dallas, he demanded quite a bit from the congregation: Services would start on time; dress was more respectful, and while church was a great place to meet people, it wasn’t for cruising.

Annette said those steps led to the growth that led to the new cathedral.

“The church wouldn’t be what it is today if he wasn’t there at that time,” she said.

The Rev. Carol West, now pastor of Celebration Community Church in Fort Worth, calls Piazza her mentor. She was the first woman licensed and ordained under him.

While acknowledging their sometimes-stormy relationship, she said, “I think Mike is a visionary. My belief is he took this community to a place they were ready to go.”

She said that when he arrived in Dallas in 1987 in the middle of the AIDS crisis, the LGBT community was doing nothing but taking care of people with AIDS.

“He [Piazza] always had a vision of the community having more,” West said. “He helped our community get our voice.”

She called him a model for many pastors and thanked him for getting her to her current position.

Cathedral of Hope’s current senior pastor, the Rev. Jo Hudson, called Piazza “one of the best and most creative preachers I’ve ever known.”

She, too, remarked on Piazza’s clarity of vision for the church from Day One.

“He gave them courage and direction,” she said. “He made the church a visible sign of hope.”

Piazza said he did three things when he first arrived that helped the church become what it is. The first he called “big worship.”

He said when he arrived in Dallas, the church was already doing enthusiastic, joyous services well. He helped make it bigger but also made sure it was visitor friendly.

Visitors needed to be welcomed and the service had to be easy to follow, Piazza said. That included simple things like a service bulletin that was done well.

Visitors needed to be welcomed and the service had to be easy to follow, Piazza said. That included simple things like a service bulletin that was done well.

But the congregation also needed a sense of community, a sense of intimacy, Piazza believed. To accomplish that as the church grew, small groups were formed to keep people engaged.

“That way it didn’t matter how big we became,” he said.

The third component was community service, and that, Piazza said, gained the church respect.

“This church gave away hundreds of thousands of dollars,” he said.

Piazza related a story told by the Rev. Paul Tucker, who is now senior pastor at All God’s Children MCC in Minneapolis, about a conversation he overheard at a diner in Oak Lawn.

“We were in the paper for something like air conditioning Maple Lawn Elementary School’s gym. These two old codgers were sitting behind Paul reading the paper, and they were talking about the church. One said, ‘I don’t know about this queer stuff, but that church does more good than any other church in this city.’”

One of the programs Piazza started soon after he arrived was a weekend hot meals program for neighborhood children. The area around the church on Reagan Street was very poor and children who were fed in school during the week were going hungry over the weekend.

“Men in wheelchairs with AIDS would come to feed those children,” he said. “This church became respectable.”

So respectable and even admired that even Criswell had to stop denouncing Piazza and the church from the pulpit. Groups like the KKK stopped picketing them. The council of churches approached Piazza and begged the church, to join. Piazza refused because by that time, the church had nothing to gain from council membership.

Controversy

But as the church grew, so did controversy. As the congregation raised money to build the new cathedral designed by Philip Johnson, allegations of financial mismanagement arose.

The national Universal Fellowship of Metropolitan Community Churches (the denomination now just known as MCC] was called to audit the Dallas church’s records.

But Cathedral of Hope’s budget was larger than the denomination’s, and the denomination was unequipped to deal with the controversy, Piazza said.

One woman who didn’t like the way the church was being managed filed a complaint of financial mismanagement against Piazza. At the time the board was overseeing financial management, not Piazza.

Because the denomination didn’t have the staff to look into the allegations, MCC hired private investigators. The investigation dragged on for months, until finally, the cathedral’s board of directors had had enough. The board members called a congregational meeting, and the congregation voted by a 90 percent margin to leave MCC.

Piazza looks back now at the conflict with a philosophical eye. He said that much of it was rooted in theology, although that never got named.

For years, the cathedral had been moving away from MCC, which Piazza said is rooted in much more conservative theology.

He said that part of the 10 percent voting against leaving were simply people who had been a member of MCC for decades.

But Piazza admits missing the significance of the vote at the time.

As they voted to leave MCC, they also elected Piazza as the pastor of the newly independent church by the same 90 percent, an overwhelming vote of confidence by any standard among churches of any denomination.

“If I didn’t piss off more than 10 percent of the congregation after being here for 17 years,” he said, that was a great accomplishment in itself. “It was one of the greatest affirmations of my life — and I missed it entirely.”

When Piazza thinks now about mistakes he’s made over the years, he quotes Michael Jordan, who said, “I missed 9,000 shots and that’s why I succeeded.”

In other words, the church moved forward by always taking chances.

Piazza said that sometimes they hired someone who turned out to be a mistake, but other times they took chances and hired people like Tucker and West, who he called heroes.

“But sometimes, you just have to make mistakes and you learn from them,” Piazza said.

Plunkett called innovation part of Piazza’s legacy. He said that he started attending services at Cathedral of Hope via the Internet while he was living in Reno.

“Television was extremely expensive,” Plunkett said, so Piazza broadcast services on the Internet.

He was ahead of the curve and his worship style came through on line.

“I felt connected to a larger community,” Plunkett said, even though he lived in a smaller city with nothing comparable to Cathedral of Hope.

Family in transition

Once Piazza decided to take the position in Atlanta, several things fell into place. He and his partner, Bill Eure, put their house on the market and had an offer the next day from the first person that looked at it.

Eure works for American Airlines, but works from home and does not need to be in Dallas for his job.

Piazza said that when he stepped aside at Cathedral of Hope, Eure also withdrew from the congregation. Virginia Highlands gives him a place to begin an active church life once again.

Together they raised two daughters with the girls’ mother.

Their older daughter graduates from Booker T. Washington High School in May and will be in college next year. Their younger daughter is a junior at Townview Talented and Gifted. She’ll finish the year in Dallas and the family is deciding whether she’ll transfer next year.

Eure will remain with them in Dallas for another couple of months until the house sale closes.

Hope for Peace and Justice

The future of Hope for Peace and Justice is undecided.

Piazza writes Liberating Word, the daily communication sent to 13,000 subscribers. He described the writing as a job no one else wants and one that he can continue from Atlanta.

But day-to-day management in the Dallas office will pass to someone else, he assumed.

The board is meeting this month to discuss what direction that organization will take after Piazza’s move. Its Art for Peace and Justice division also recently lost its director, Tim Seelig, who moved to San Francisco to become director of the San Francisco Gay Men’s Chorus.

Coincidentally, Seelig and Piazza also arrived in Dallas at the same time.

Many of the Art for Peace and Justice events take place at the Interfaith Peace House so moving the group to San Francisco with Seelig was not feasible.

“You can’t replace Tim,” Piazza said. “He has such a unique place in the community.”

Piazza said that that group would reinvent itself.

Seeing the end

Cathedral of Hope will continue to change and flourish, he said.

Someday, he said, the Johnson cathedral may be built. He said that no cathedral has ever been built by a congregation alone. It takes an entire community.

“We’ve always framed it as either it happens or it doesn’t happen,” he said. “We were always really clear that if the larger community doesn’t decide to participate in it, it just won’t happen. We just don’t have the resources ourselves.”

But he said the church continues to work at building relationships with people who do have the resources.

“We’ve done a piece of it and I think that’s really important,” he said.

Piazza said that when he hired Hudson as pastor, he knew, “My time here is limited.” She became the local pastor and he knew that if things worked well, she would become his replacement.

For the first two years, she worked for him. Then they switched roles.

“While she was a great pastor,” Piazza said, Hudson had never managed a multi-million dollar budget. She agreed to become the senior pastor if he stayed to help manage the church finances.

So for the next two years, he worked for her. During that time, he phased himself out. For the past year, he has had no official affiliation with the church even though his office has remained in the Peace House, which is attached to the building.

“It’s good timing for me to not be here anymore,” Piazza said. “It’s time for this place not to be haunted by my ghost.”

Hudson said that Piazza’s life has been devoted to working for justice for the LGBT community and fighting for what’s right for all people.

“Working with Michael has been glorious, creative and exciting,” she said. “Our time together has been a great gift in my life.”

She said she hopes he’ll be remembered in Dallas for single-handedly saving people’s lives.

“The work he will be doing at Virginia Highland Church will be an incredible new chapter in his life,” Hudson said.

Piazza said he runs into people at the grocery store regularly who ask him the next time he’ll be back to preach and he thinks, “I don’t work there anymore.”

But he said the transition was so gradual, “that even this congregation doesn’t know. They just think I’m off traveling.”

Many people hoped that Piazza would give a final sermon before leaving for Atlanta, but he said they’ve already transitioned. He compared that to a Texas funeral, more popular when he first arrived in Dallas, where they reopened the coffin at the gravesite after the funeral service.

“So someday I’ll come back and preach,” not in six months, but maybe in a year or two, he said. “For me, this has been a long goodbye already. We don’t need to make it any longer.”

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition Jan. 18, 2011.

Piazza did a lot of great things for out community and he’s been a wonderful pastor and a magnificent preacher. He’s also been a very divisive and controversial leader. The financial scandals and the triad relationship have hurt the Cathedral and the community. It’s time for him to move on. Jo Hudson is far worse and hopefully the church will look to someone of integrity for a leader and once again become a great church.

Yes, Mike Piazza has always been the amazing speaker that he truly is, in more ways than one. The history of the growth of The Cathedral of Hope is extremely rich as well as having been a gift to the gay community and to the City of Dallas. And we have Mr. Piazza to thank for all of that. The legacy that he has left to our community however, has been extremely questionable, to say the least, particularly since he left the reign of power and leadership several years ago to the current Sr. Pastor Jo Hudson. From a financial standpoint, controversy and so many other issues, things seem to have gone downhill since Jo Hudson entered the scene at The Cathedral. So many of my friends, including my partner and I have since left this church shortly after Mike stepped down as Sr. Pastor, mainly because it just has not been the same without his leadership. This church has always considered itself to be a place of relentless compassion and radical inclusion and the current Sr. Pastor Jo Hudson has not set a good example of practicing these thought processes. Her leadership has centered more around controversy, scandal and financial mismanagement in the past few years, than about being the Christian-oriented pastor that she is supposed to be. I wish Mike Piazza well in his new spiritual journey in Atlanta and I can only hope and pray that the legacy that he has left being at The Cathedral of Hope here in Dallas will see brighter days ahead.

The end of an “era” here in Dallas. Best of Luck Mike in Atlanta.

Yes, Mike Piazza has always been the amazing speaker that he truly is, in more ways than one. The history of the growth of The Cathedral of Hope is extremely rich as well as having been a gift to the gay community and to the City of Dallas. And we have Mr. Piazza to thank for all of that. The legacy that he has left to our community however, has been extremely questionable, to say the least, particularly since he left the reign of power and leadership several years ago to the current Sr. Pastor Jo Hudson. From a financial standpoint, controversy and so many other issues, things seem to have gone downhill since Jo Hudson entered the scene at The Cathedral. So many of my friends, including my partner and I have since left this church shortly after Mike stepped down as Sr. Pastor, mainly because it just has not been the same without his leadership. This church has always considered itself to be a place of relentless compassion and radical inclusion and the current Sr. Pastor Jo Hudson has not set a good example of practicing these thought processes. Her leadership has centered more around controversy, scandal and financial mismanagement in the past few years, than about being the Christian-oriented pastor that she is supposed to be. I wish Mike Piazza well in his new spiritual in Atlanta and I can only hope and pray that the legacy that he has left being at The Cathedral of will see brighter days ahead .

I would like to personally thank Rev. Piazza for his work at the Cathedral of Hope. I have never seen a pastor want to “get it right” so much, not for himself though, but because he knew that in general the CoH only had One chance to get a visitor to come back. I remember my first time coming to the Cathedral, I sat in one of the back rows, not sure what this church was all about, I cried, oh how I cried, it wasn’t because his sermon was some type of emotional pep rally, it was because I felt the presence of Christ in the church, I felt that he truly meant what he said, and to this day I still do. I’ve been an active member now for over 11 years, I wouldn’t change anything that I’ve experience at the CoH. Rev. Piazza, if you read this, may the words you so often spoke to us when you’d give your benediction, ring true to you today, Our Worship has ended, but now Our Service begins, go from this place, You are the body of Christ, so the whole world awaits you, Live passionately, Love faithfully, and celebrate Every moment from now until the Finale, for the God of Hope, goes with you.

Michael Piazza and the Cathedral of Hope saved my life. He is and has always been one of my best friends since the day we met in April, 1990. He knows me better than any lover I’ve ever had and that’s a great treasure to me. And yes, the Cathedral of Hope will continue to flourish because of his legacy and Virginia-Highland in Atlanta will become a great church once again under his vision and leadership!

What a wonderful Sunday service Piazza created at CoH, but what a disaster in management of church finances and staff management. He needs to go where he can control everything and have a congregation who, like sheep, will let him. Thinking congregants require more of a spiritual leader. The Board of Directors at CoH was in actuality Mike Piazza and today Jo Hudson continues that tradition–the congregation who supplies all of the funds for the church has no voice. The Board tries to make it appear the congregation has a voice, but it’s all smoke and mirrors. Maybe one day they will wake up and reailize this can’t continue without serious consequences for the future viability of the church.

I totally agree with Neil Thomas! I’m so glad he’s leaving…only 20 years or so too late. He misused his authority (and once even admitted it), but people looked the other way. I vowed to not return to CoH until he left, and then the exact same thing has happened with Jo Hudson. I really wish that the congregation would take stock of what’s happening and do something about it.

There is so much to be done and so much that COULD be done if the CoH were about God and not about ‘power’ and money.

If you posit that the purpose of a Christian church is to create an atmosphere that mimics the teachings of Christ, and by that I mean an atmosphere of acceptance and forgiveness of ourselves and others, help for those who need it, all unnderpinned by a sense of the peace of Christ and the unconditional love God has for his children, then The Cathedral of Hope is a beacon for all those things, and Mike Piazza has been its main architect. That is not to detract from those who came before him, from those who follow him, or from those who helped him in his vision while he was here. But by any measure you choose, Rev. Piazza has succeeded beyond the expectations anyone had of him when he arrived at COH. His detractors can point to his shortcomings and mistakes all day long, but in the end, he leaves a unique and unmatched legacy in the Cathedral of Hope and its message of love, tolerance, and care for our fellow humans—truly a legacy for our community, for the City of Dallas, and for peace-loving Christians everywhere.

As a longtime member of the Cathedral of Hope, I think it is important to offer a different point of view than the one that, unfortunately, is so often heard in the comment section of Dallas Voice articles.

It is absolutely true that Michael Piazza’s leadership at CoH has not been without controversy, as is the case with most public figures today. Sadly, people today feel it is their right to pick apart , criticize, and publicly denounce other people when they disagree with them. The truth is that Michael Piazza has done amazing things over the last 23 years at this church and Jo Hudson continues that tradition. This is a church and congregation that give so much back to people outside the walls of the church. It is a church that Jesus Christ would recognize. And anyone who doesn’t believe that this is what is most important to both Michael Piazza and Jo Hudson don’t know either of them.

Thanks to Michael’s vision, Jo’s steady and loving guidance, and the hard work of countless ministers of this church, people’s lives are not only changed, but literally saved every single week.

To the Long Time Member—Trust me, I DO know Jo Hudson and what she is all about and she DOES NOT even come close to the hard work that Mike Piazza has put in over the years!!!!!!!

We can only say “ditto” to the comments of Tim Wiersma above, and wish Mike and Bill Godspeed in this new chapter of their lives together. Although we moved to Mexico several years ago, we still visit the C.O.H. whenever we’re in Dallas, and our love for both Mike and Jo is a part of who we are.

I think the controversy was a bigger deal that your portray. Someday, some member of the press will bust this church wide open. When they do, the gay press will be left with egg on it’s face for avoiding the issue.

We should all thank God that Michael Piazza is finally leaving the Cathedral of Hope as well as the metroplex. Hopefully now that Michael is leaving, the church might be able to thrive instead of having to financially support Mike’s projects (Hope for Peace and Justice). Hope for Peace and Justice was a wonderful organization for creating change in the world, however, since Michael’s fundraising plans always cost the Cathedral money there was no way for it to thrive. The only good thing that came from Hope for Peace and Justice was the Voices of Peace concert that was produced by Tim Seelig.

For the Cathedral March 1st will be a day of liberation from the insanity that Michael exudes on a daily basis. Congratulations Rev. Hudson and the leadership of the Cathedral of Hope for finally being out of the hands of this tunnel-visioned tyrant.

I was inspired to join the Cathedral because of Rev. Piazza. I have never heard anyone who can deliver s sermon the way he can. The work he did when he arrived in Dallas for people with HIV and AIDS is a testimony to his compassion and dedication. I commend him for the 99% of what he has done that has been spot on! We should forget the other 1% because we should remember that the one who is without sin can cast the first stone. I wish him the best and I know that we will hear about the great things that he will do in Atlanta. His successor, however, has done a lot to hurt the church and the Body of Christ. Two years ago, the Treasurer of the Board and the Minister of Finance resigned within five days of each other due to financial and moral irregularities. I was disenfranchised and expelled from the church for asking questions. People who have publicly criticized Jo Hudson have received “Cease and Desist” orders from one of the largest law firms in Dallas. So much for “Radical Inclusion”. She has built her chapel but she has also doubled the long-term debt of the church and alienated dozens of people and the offerings are dangerously low. She should do the right thing and step aside and the church should find someone to restore integrity and transparency.

Hey Mike…Can you take Jo and Shelly with you to Atlanta?

I am a former member of CoH and a former board member of “Hope for Peace and Justice”. All I can say is that:

1. There is Hope.

2. I am at Peace after leaving CoH.

3. Now, all “those who serve Jo Hudson shall receive their Justice?”

For those slamming on Piazza, I challenge you to look at any church and find one that does not have controversy. Churches and their congregations live on the financial contributions of the wealthy and the last dimes of the poor. Get over the “financial irregularities and crisis and see all the good that Piazza led the church towards and what they have done for the congregation and the communities surrounding the church. Afterall, if you don’t agree with those leading, you are welcome to go somewhere else. Who’s keeping you here?

Yes, Becca you are so right. We should forget that Piazza did not want to give financially to the MCC. Let’s forget about the countless alterations he had with people who felt defrauded and devalued. Let’s even forget that his greed took precedence over the spiritual guidance he dispensed. He did so like a Physician dispensing medications. His greatest achievement was hiring that Narcissist Jo Hudson. So, you’re right Becca.

I think it is quite obvious here that many folks will miss Mike Piazza for the many years of service that he gave to the community here in Dallas and for the legacy that he is leaving behind. Yes, I too, as a former member of COH, have had my issues with Mike, Jo Hudson and the COH Board of Directors in the past and we disagreed on several issues that eventually led to having my membership revoked, simply for telling the truth. But I am not totally blaming Mike for everything that happened when myself, Gene and Blake (more commonly known as “The Trio”) were kicked out of COH and had our memberships revoked by current Sr. Pastor Jo Hudson over 2 years ago. Based on this article and previous articles about COH that ran here in The Dallas Voice over the past 2 years, I still believe that the 3 of us DID indeed do the right thing, by exposing financial improprieties and unethical behavior at COH. And based on many comments that I have read on this article tonight and in previous articles about COH that have appeared here, it is also quite obvious that many folks are still not satisfied with the direction that Jo Hudson has led this church since Mike stepped down. I think people are finally starting to get the message.

Last year, when the issue of gay-bullying was making local and national headlines, Mike wrote a very moving article regarding this subject and I was touched and moved by his comments, and realized that yes, he can be compassionate on sensitive subjects such as this, regardless of our disagreements in the past. Yes, Mike has made mistakes, but then again, haven’t we all. None of us, including myself is perfect and all I can do at this point is to wish him well in Atlanta and to leave the past behind us, where Mike is concerned. As for the future of The Cathedral of Hope here in Dallas under the current leadership of Jo Hudson, well, as the bible says—-“Beware of False Prophets”!!!

Living in France, I follow CoH closely and am I regular worshiper. Thanks to Mike Piazza and also Jo Hudson, the church is one of the most remarkable places I know. It is surely holy ground, a place where onecan be at peace with one’s neighbour and feel the presence of the living God.

In my humble opinion Mike Piazza is agreat prophet and man of God who is being followed very abely by Jo Hudson. “Nobody is perfect” and unjustiable and unnecessary criticism is what I would consider hitting below the belt. Noone can do better than his best and, we must remember, I think that we all have faults and weaknesses; Jesus, Himself, was controversial in his time. I wish Godspeed to Mike & to Bill, who I do not know and am confident that Mike’s legacy will be surely developed by Jo, in whom I thik we may have all confidence

I think Jane is yet another pitiful example of the hypocrisy that so many unfortunate people are living these days, who fail to see the light of what is truly right and what is truly wrong in the House of God. Thanks so much for your “kind words” Jane, because you proved for me once again, how right-on-target “The Trio” has always been on this subject.

Where is Christianity in all of the belittling remarks? Rev. Dr. Jo Hudson, the CoH Board of Directors and all the lay ministers show the strength of the love of God that is so strongly exhibited when one walks through the doors of CoH. My life was changed when I first entered the building many years ago. Michael Piazza was and continues to be a very strong minister of God’s word and did great, compassionate things for many people. As he said, it is time to move on. Rev. Dr. Jo Hudson exhibits her love of God and her love of CoH and her love of the congregation with every thing she does. Our church WILL continue to be strong and one that reaches out to others with love and compassion. Many lives will continue to be saved—just as mine was. LET THE PAST GO.

Leaving comments reminds of me the bad service someone receives at a place of business. The negative comments always are more common than than the good comments. With that said, I am very active in the chuch and COH has done many great things and continues to do great things! Thanks to Michael Piazza for his legacy and Thank you to Jo Hudson for all the great work you do!! Rev. Hudson’s “fans” out number the “nay-sayers” 100 to 1!! Keep up the GREAT WORK! And if you have never attended Cathedral of Hope, I invite you to do so to see for yourself.

I think Jane sums it up best. Anyone who questions the finances of COH must certainly be mentally unstable. Even the COH treasurer admits to a waste of money. Hard earned money given to a church in a time on financial hardship. Like, why does Piazza demand a greenhouse for his office? How does that help people on a spriitual journey? Several people feel ripped off by this church and for other church members to belittle them is proof they are not walking in light but in power hungry greed. It is really ugly.

A comment attacking Michael Piazza and Hope for Peace and Justice that was previously posted here and attributed to Jeannette Garcia, treasurer of the board of directors for Cathedral of Hope has been removed because it was posted by someone other than Ms. Garcia who apparently used Ms. Garcia’s name to try and create conflict.

In my opinion, Mike Piazza’s legacy is yet to be written (or fully appreciated). No doubt he is leaving a trail of incredible accomplishments in Dallas unmatched by anyone. While his name may not be on the building, his imprint will always be on the Cathedral.

It is always easy to pick out or magnify missteps along the way. But there is no escaping the fact that he dragged a significant majority of Dallas, albeit kicking and screaming to giant leaps of consciousness and compassion. Mike was shoulder-to-shoulder with many of us in the trenches during those times when filling trenches wasn’t so easy and equality or access to adequate healthcare was but still a dream.

I presume different experiences create different realities, but my experience consisted of seeing Mike in his collar at wakes, hospitals and risking arrest at protests and demonstrations. Even Mike would deny he’s a hero. But no one was quicker than Mike to accept his responsibilities to his congregation and advance our community.

Priceless.

I have been in Dallas for about 10 years now and have attended The Cathedral of Hope several times in the past, though I have never become a member, nor do I attend this church on a regular basis. I have read many of the articles on this website over the past few years related to this church, but have never posted any comments to any of these articles until now. What really concerns me here is that I have never read so much fuss and disagreement before, regarding the workings and inner-workings of a religious organization, its leaders and its congregation, and this is not a healthy way to live a Christian lifestyle, FROM EITHER SIDE OF THESE ARGUMENTS. I guess this is part of the reason why I have never been involved in organized religion on a regular basis. And this church seems to be no different, regarding controversy, than any other church. I am a devout Christian and am also proud to be homosexual AND I do take my faith seriously. But it seems that everyone here who is for and against this man, Mike Piazza and the Sr. Pastor Jo Hudson would be setting a better example by not continually attacking each other. I’ve met Mike Piazza a few times in the past at this church and he was ALWAYS kind to me and to my friends when we would enter and leave this church. Jo Hudson has always been just as gracious as to us as well, and I had the opportunity to chat with her in person just once, for a few minutes about a year ago. Nothing but kind words were spoken to me from Jo. But at the same time, what is really very sad to me is that I have heard nothing but negative things about this woman from several of my friends who have attended this church. I don’t like to judge anyone here, including Jo Hudson and I have nothing to base this on, and it really confuses me. If she has done anything wrong regarding her work in God’s House, then let God be the judge of that, AND NOT ANY OF US WHO ARE EITHER FOR OR AGAINST HER. Yes, there may be some basis and truth from those who have accused her of these things, but at the same time, it gets us know NO WHERE in the Christian world, and what is worse is when her supporters in this congregation continually seem to fight back, by attacking those who dislike her or her actions, because they too, are not setting a good Christian example and are no different than her accusers. If everyone on both sides of these debates, who reads these articles, who posts these comments and who attends this church could see each other on both sides as God-loving Christians AND looks past their differences and disagreements, then God would truly be pleased with all of us. And that goes for Mike and Jo as well. I can only imagine what must go through their minds and their hearts when they read these comments and I hope and pray that they Mike and Jo have the strength to deal with it, regardless of what the truth is or is not. I commend them for their courage to carry on in a difficult world and in a difficult community where unfortunately, so many differences do exist. If the gay community and its religious community, either in this city or around the country cannot support each other and cannot unite as one, then mainstream society will never accept any of us for who we are and we may never reap the rewards that we truly deserve.

First, to Jo Hudson and Mike Piazza: I am so thankful to know both of you and to call you my friend. Not only do you give your life away day in and day out to share hope and healing with others, but then you have to withstand the onlsot of personal attacks, like the ones above.

I wish each person who has criticized you would take just a portion of that energy and judge themselves……….. then, I am certain the criticism would cease. I am one of millions of people who have found hope, encouragement, healing and purpose through your lives and the ministry of the Cathedral of Hope. My best to you, Mike and Bill. I am excited to see all that God has in store for you in this new chapter of your lives. Jo, your purpose is great here, so keep up the good work. Ignore the words of ignorance and as the line from Sordid Lives says “just file you (the above comments and individuals) in my loser-flake file!

Here’s to HOPE!!

I do not support a church on the basis of my like or dislike of a pastor, It is the mission statement and the creative and effective ways that a church gives life to its mission that I support. In my now seventy years of church life in multiple denominations none promotes mission and values with more consistency, more fervor, and more effectiveness that the Cathedral of Hope. I have experienced both Mike and Jo and find them both to be leaders on target and messengers in clay vessels. I like that because at best that is what I can be: a clay vessel mostly on target. I am saddened that some who have had past disagreements with a pastor have missed the point of the SERENITY PRAYER: “CHANGE WHAT ONE CAN CHANGE, ACCEPT THAT WHICH CANNOT BE CHANGED, AND PRAY TO KNOW THE DIFFERENCE. I fear that the the acid expressed by many contributors is too old, too stale, and too visceral to change one thing. Accept and Move On please and trust that pastors are worthy of the same forgiveness as you and I. This is sent in love from John L, The Cathedral is on the move and living fully in today. The Journey is just fine!

Kudos to both Mike and Jo for a job well done. We need to put the past behind up and move on. Good luck to Mike, Bill and David. We all hope that you will come back and visit us as often as you can.

What a great, comprehensive and unbiased story. When I voted to call Rev. Piazza to Dallas in 1987, I never dreamed I would be commenting about his legacy almost 25 years later. As for those who are still criticizing and pointing the finger (and whining, for lack of a better word), even after Rev. Piazza has left the city (yes, that’s what the article said–he’s GONE!), well…the rest of us can simply rise above the negative energy and pettiness of those individuals who are unable to look to the future because they are too focused on the past, and obsessed with their own self piety to do so.

Godspeed, Michael and Bill. Onward and upward.

Wow, so much negativity under this article since my last post a few days ago. As several have already stated, yes, we should all leave the past behind and just move on. And like so many others, my friends and I are so much more at peace, since leaving The Cathedral.

In order to create Peace there must be Justice. The people who worship Jo Hudson don’t understand this principle. They are “sheeople”. Wake up “sheeople” before before that Church implodes.

We attended COH several years ago and it was very apparent people were in awe of Piazza and not God. He had just built a truly beautiful church (the current structure) and almost immediately his ego demanded this large “iceburg” cathedral be built. People were dying of HIV/AIDS and needed food and drugs and Piazza needed his great white whale. Now they’ve built it in miniature and it looks like a shed. How many people could have been comforted in their last days or had their lives extended with the money the “Cathedral Builders” poured into Piazza’s folly. Jesus never collected for a building fund.

Piazza is all about Piazza. It was amazing to see him knife the Rev. Mona West in the back as she held the congregation together during the financial crisis. Then he “steps aside” and becomes the man behind the curtain as Rev Hudson plays the public role. I don’t know Rev Hudson but I hope she can distance herself from him in some way. I say don’t let the door hit ya, Mike. Atlanta, be warned.

Vincent (and others), i hear what you’re saying, but for those who know what’s been going on in the background for many years, they (we) have a legitimate complaint(s) to offer. this is just another forum for people to express their disappointment with the past and present that has been created.

it’s also a forum to possibly educate others so as not to be taken in by those ‘leaders’ who are mostly self-serving. does this mean we don’t love God? of course not! if anything, it shows how much more we DO love God and want the true opportunity to worship Him without the human egos in the middle. it isn’t just controversy, it’s also being mislead by our spiritual leaders (?) and the responsibility they have committed to follow when they accepted their postions. it SHOULD all be about God. THAT’S our point!

it isn’t about bashing. it isn’t about being judgemental, it’s about expressing the truth as we see it from the monetary mishandlings to the ego feeding projects, and much more, not based on hear-say, but based on facts as they happened…witnesses to what was going on AS it was going on. maybe now we CAN move on and find some healing in the community. maybe now we can find a way to get the church back to God and worshiping Him. maybe now is the time for things to change to create the kind of fellowship that we should be able to experience by service to God and what He wants for us and others through us. let’s pray this will be a chance for all of this and more to happen.

Atlanta’s loss is Dallas’ gain!

I must thak him personally for filling me with the belief that I could be a gay Christian and that God loves me. That breakthrough was one of the most important moments in my life.

<>

New American Standard Bible

35‘For I was hungry, and you gave Me something to eat; I was thirsty, and you gave Me something to drink; I was a stranger, and you invited Me in; 36naked, and you clothed Me; I was sick, and you visited Me; I was in prison, and you came to Me.’

Perhaps once Rev. Piazza is solidly ensconced in Atlanta, this publication can once again become the Dallas Voice instead of the Mike Piazza Journal. During my 24 years in this city I do not think a week has passed without some major coverage of this jackleg preacher. Perhaps he can lovingly guide or fleece this new Atlanta flockby guaranteeing that they have a place at the Jesus table………

To Gene and others:

First I want to complement you for stating clearly your concerns without being full of venom and and being visceral. I understand much better the concerns you feel strongly about.. In your words you are disappointed about the past and the present that has been created,

And how full of promise is your last paragraph which imagines a future. You write “Maybe now we can find a way to get back to the worship of God. Maybe now is the time for things to change”….Let’s pray this will be a chance for all of this and much more to happen.”

Let me tell you that your hope and prayer is a shared one. Such is my prayer that we can share a common effort to help our prayer be answered in a way that God can bless and sanctify.. This can be done if we if the past either/or solutions are put on a back burner and we Maybe work toward that which is ” truly new” believing that God fulfills the promise “Behold I will make all things new”

Lastly I tell you that your last paragraph contained fresh hope for mending the tear in the fabric of our church family. I feel that I am one of God’s kids that stayed at home. You were one of the kids who went away. Both of us were part of a breach in the family . But the story of Jesus was really about neither of us. Instgead it is about the will and hope of our Parent

The Voice has never accurately reported the real story of how CoH left the MCC denomination. This article is no exception, making it sound the like the board just got fed up with the investigation into Piazza and then called for the vote on disaffiliation. The real story is that after a lengthy and exhaustive investigation MCC was about to release its findings, which could have been extremely detrimental to Piazza, and possibly incriminating. Piazza was getting legal counsel throughout the process. By resigning his clergy credentials at the last minute, that stopped the denomination from releasing its findings, because it then lacked “jurisdiction” to discipline a pastor no longer part of MCC. Piazza then pushed to withdraw from the denomination, because he could no longer be licensed in it. Of course 90% voted in favor since Piazza had effectively cut off all interaction with MCC for years, and most members were not even aware they were part of it. The vehement anger and hostility toward MCC during the disaffiliation process was anything but Christian. From this sad legacy CoH seems never to have recovered.

Pete, i’m sorry to say that you are correct that CoH’s reputation has been tarnished and hence lost many followers. unfortunately, as long as the people who have so closely affiliated themselves with Piazza, people who covered and coverted with him, are still very much still a part of CoH. until those affiliations are removed, i sincerely doubt that things will change. knowing the details or not, God will reveal enough within the Spirits of the Body for discernment. when there is division in a church and it is evident that God is no longer the focus but rather the ‘leaders’, people who are truly looking for Spiritual guidance will be led to other places. as far as i know, being an active member at the time, i don’t recall a great discord with the affiliation with MCC as far as the church members, themselves. the problems were those created by the leaders (sic) and now many who were content with the relationship between CoH and MCC have moved on. if CoH is to survive, there must be healing and proof of leadership that is not self-serving, but rather God serving. though i, personally, will not go back to CoH as it has its denominational affiliation today (and its current leadership), there are those who are taken in by the emotionally charged rhetoric and choose to stay. i am very sure i don’t stand alone in my decision to not return. it saddens me because i remember the beginnings of this congregation and the struggle to exist and thrive as a church full of love and acceptance during a time when much of the mainstream “Christian” churches were preaching separation, if not hate. but even then there were struggles with the leadership (Piazza) and MCC. many other MCC affiliated congregations began to spring up all over the metroplex, meeting in hotels or small, rented buildings… but the passion to find a church that truly was searching for growth in Christ burned fierce. to this day i and many others are still trying to find that same type of congregation…without much success. i do so pray that this move will begin the healing that is so desperately needed within the church and within the community. if we can’t turn to a place of worship and find goodness, love, compassion, and a will to follow God in a sincere fashion, then what do we have? i’m sorry to say that i still feel the void, as do others, any my search continues. i wish it could end where for many it began….Cathedral of Hope.

I knew Piazza when he first came to Dallas, many years ago. After all the damage he has inflicted on the community, all I can say is “Good Riddance!” I pity the people at Virginia Highlands.