Was the Wild West outlaw bisexual?

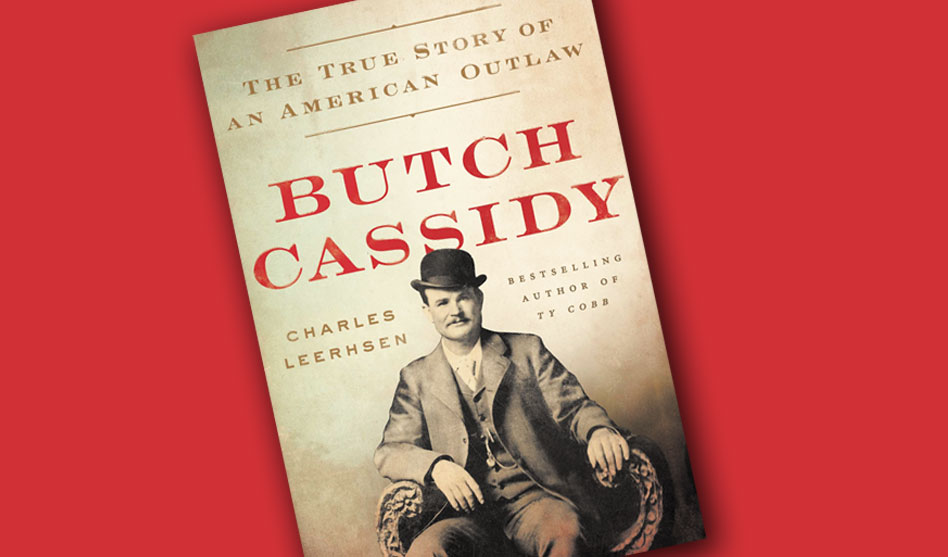

Butch Cassidy: The True Story of An American Outlaw by Charles Leerhsen (Simon & Schuster 2020) $28; 304 pp.

Eight years before the 1969 release of the film Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, the last of Cassidy’s Wild Bunch went into the ground. Her name was Laura Bullion, and she was one of a small handful of female groupies who followed the outlaw gang. “It was easy,” Charles Leerhsen writes, “to be smitten by Cassidy.”

Born Robert Parker in a tiny cabin in Beaver, Utah, Cassidy grew up uninterested in both his parents’ farm and his ancestors’ Mormon religion. He was too fun-loving, too full of mischief and too appreciative of guns, horses and gambling to settle down. And yet, unlike many contemporary scoundrels, he was well-read, kind and goodhearted, which, in the hearts and minds of Old West citizens, set him apart from all the others during his life of crime. Later, though apparently not deceitfully, he began using “Cassidy” as a surname, alternating with his given name.

Despite its appeal as an American legend, however, the story of Butch Cassidy and Harry “Sundance” Longabaugh might’ve merely folded into history were it not for Hollywood, although the movie messed with the myth. Reel men and real men were two different things, and, writes Leerhsen, it’s possible that Sundance wasn’t even Cassidy’s best friend, that their bones may not lie in South America, and, perhaps most surprisingly, historians believe that Cassidy may have been bisexual (indeed, Cassidy’s mother commented on it). About the bank heists, train robberies and horse thefts? Cassidy was a criminal, but was Hollywood correct in portraying him as extraordinary? “Oddly enough,” writes Leerhsen, “the answer, it seems, is yes.”

Thankfully, that doesn’t mean a cliched riding-off-into-the-sunset scene inside Butch Cassidy. There’s no such sentimentality here. Instead you’ll find lots of delightful set-you-rights and the chance to meet a roguish scoundrel who’s hard to historically hate — a notion that many of Cassidy’s victims would have surprisingly agreed with.

In explaining why that’s so, Leerhsen shows why Cassidy’s exploits loomed so large in the West but were then largely forgotten for so long. In this, readers may get the sense that the movie memorializing didn’t please Leerhsen and that he is no fan of the general Hollywoodization of history.

But that’s one small part of what’s here. The real appeal of this book — what’s fully half the fun of it — is the sense that Leerhsen isn’t just telling this tale. He’s growling it, grizzled-like, perhaps over campfire and cowpoke stew, surrounded by rustled cattle.

— Terri Schlichenmeyer