Armie Hammer and Geoffrey Rush in ‘Final Portrait’

Quirky writer-directors delve into creativity, humor and horror

ARNOLD WAYNE JONES | Executive Editor

jones@dallasvoice.com

Final Portrait. In 1964, a gay journalist named James Lord (Armie Hammer), staying in Paris, agrees to sit for the ageing artist Alberto Giacometti (Geoffrey Rush) for a portrait — a sitting, the maestro insists, that should take no more than an afternoon. Weeks later, having irritated his boyfriend back in America to no end with one postponement after another, Lord still hasn’t seen the completed work. How hard can it be?

Frustration with “the artist” is a recognized subgenre in the category of movie biopics, whether writers (Julia, Midnight in Paris, Before Night Falls), musicians (Shine, Bird, Inside Llewyn Davis), sculptors (Camille Claudel) or especially painters (Pollock, Lust for Life, Basquiat, The Agony and the Ecstasy), and are usually filled with shopworn tropes: Mental instability (often fueled by alcohol or drugs), tragic outcomes, under-appreciation in their lifetimes. But Final Portrait contains virtually none of those. (It does include a fourth — sexual voraciousness — but ah, well.) Giacometti is quirky and infuriating, often impenetrably so, but Lord is his willing victim, an observer oddly intrigued at being the observed, whose growing anger is mollified by the idea that the process is the art.

None of these insights are especially groundbreaking; Final Portrait is not a groundbreaking movie. It is, though, a firmly entertaining one for what it is. It starts off at the edge of experimentalism: For a while, the images are abstractly composed and edited so that the camera is rarely focused on the person talking. It conjures a dreamy internal monologue. But that eventually gives way to quaint set-pieces with Lord on the phone to the U.S., changing his travel plans, his eyes darting as he wonders what he got himself into. And Hammer, already pretty to look at, makes for a welcome object of our gaze.

But the film largely belongs to Rush. Rush’s film career didn’t begin until he was in his 40s, and has since been a study in unsettling character parts. His face is an amorphous glob, somehow resembling a basket of soiled laundry bewitched with eyes. His nose is bulbous, his jowls pendulant. (If you’ve ever seen Giacometti’s more famous works — his rough-hewn, elongated brass figurative sculptures — you’d swear they were all modeled by Rush himself.) Giacometti lives in a world of narcissistic desires projected into the real world as a legacy of “art” — selfish, but also affectless. He’s a spendthrift and a misery, abstruse but empathetic. The film is, at heart, a comedy, a valentine, not a tragedy. There’s a loving lightness to it all.

That tone rests with the writer-director, Stanley Tucci — best known, of course, as an actor, but with a small yet enviable catalogue of films behind the camera. Tucci is a master of parsing the artistic temperament, whether it’s of a chef (Big Night) or a self-appointed essayist (Joe Gould’s Secret) or comedians (The Impostors). His is an impressively thematically-unified body of work that doesn’t go for big, showy insights but small, intimate ones. Final Portrait is another stave in his cask of creatives mid-creation. It’s what indie filmmaking was meant for. Now playing at the Angelika Mockingbird Station.

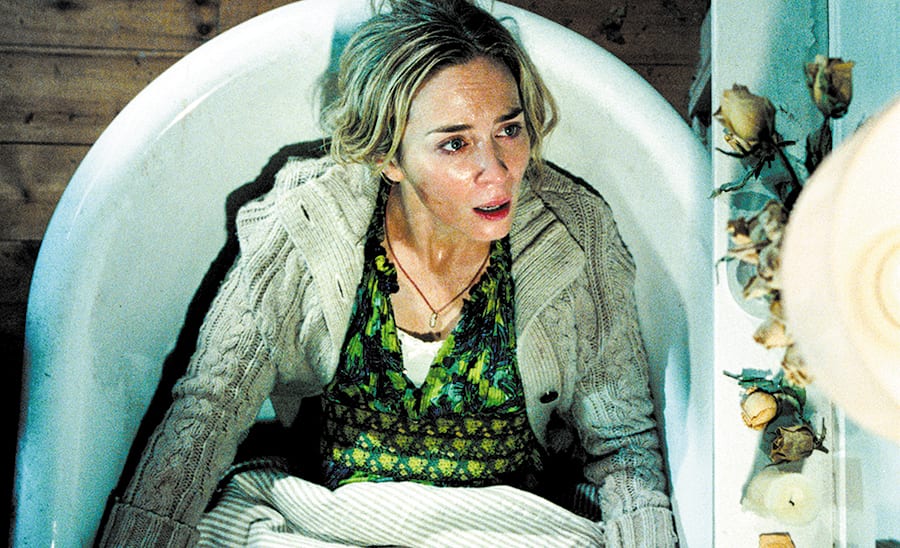

‘A Quite Place’

A Quiet Place. Another writer-director better known as an actor is John Krasinski — beloved as the goofily romantic Jim from The Office, but more serious in the family comedy-drama The Hollars and the environmental drama Promised Land. Like Jordan Peele, he has apparently found that horror-thrillers are a legitimate avenue for exploring his craft. In A Quiet Place, he shows that less can often be much more.

We’ve been acclimated to monster movies where weak humans cower in the shadows because the behemoths possess superior sensory skills, from T. Rexes attracted to movement to zombies who can smell living flesh from 60 paces to aliens who stalk best in total darkness or who sense body heat. In A Quiet Place, the Abbott family members (we only learn their names on the closing credits) walk with flashlights at night and openly during the day, undaunted at the prospect of being seen. That’s because the predators who have apparently taken over the earth are blind and noseless, but their ears? Well, they have something akin to mother hearing — make a sound, and they descend on you like Mueller on Trump associates. And when your enemy is a nine-foot tall praying mantis with rows of razor teeth, one peep is all it takes.

That means virtually the entire 90 minutes of the film are close to wordless; the noisiest things are the shrieks of terror by the audience. And there are lots of shrieks. Krasinski — who also stars with his real-life wife Emily Blunt — has constructed a tight genre film, though it might be more novelty than noteworthy if it only proved to be an exercise is discipline: “Can I keep a feature film going with only a hint of dialogue?” Even if that were its raison d’etre, it might be enough to recommend it, but the film addresses existential issues as well. How much sound do you make in a day? An hour? Heck, in 30 seconds? How do you not rattle pills in a bottle or chuckle at something amusing or creak a loose floorboard? How do you tell your spouse and kids you love them when three little words could be a death sentence? (The logistics remind me of how the novel Memoirs of an Invisible Man explored the annoying mechanics of actually being invisible in the modern world.) There’s more shushing here than at a librarian convention.

Krasinski’s sad-eyed puppyness makes him a perfect conduit for worldless expression, and no one needs to be told Blunt is a resourceful actress, but it’s their kids — Noah Jupe (Suburbicon, Wonder) and Millicent Simmonds (Wonderstruck) who turn in some potent performances as tweens with all their adolescent issues forced to grow up without foot-stomping or door slamming. A Quiet Place is terrifying, but the thrills aren’t cheaply achieved. Now playing in wide release.

‘Isle of Dogs’

Isle of Dogs. Since the 1990s, three directors — Robert Rodriguez, Richard Linklater and Wes Anderson — have basically defined Texas indie filmmaking, but of the triumvirate, Anderson has always seemed the most idiosyncratic and least Texas-y. He’s a world-builder, inventing fanciful locales within a recognizable universe with an unabashedly cinematic whimsy, whether it’s a gloriously pristine upper-crust NYC (The Royal Tenenbaums), a baroquely unlikely Eastern European resort (The Grand Budapest Hotel), a surprisingly comfortable train traversing India (The Darjeeling Limited) or impossibly prim runaways in New England (Moonrise Kingdom).

For his latest feature — like his Fantastic Mr. Fox, a stop-motion animation targeting adults, not Disney Channel kids — Anderson heads to Japan 20 years in the future, where the cat-loving mayor of the metropolis Megasaki banishes all domesticated canines to a garbage island, left to die so that his nefarious plans can be implemented. The mayor’s ward, a boy named Atari, sets off to rescue his beloved guardian, Spots (Liev Schreiber), and enlists a pack of dogs (voiced by Bryan Cranston, Edward Norton and others in the Andersonian orbit) to help him in his search.

The imagery in Isle of Dogs is charmingly wacky, from the cotton-ball dustups occasioned by dogfights to the stare-directly-into-the-camera perspectives to the Rube Goldbergian fascination with contraptions. But the humor arises from a heartfelt love of how flawed we all are, and acceptance of those flaws (one of the dogs is an inveterate gossip; one a dyed-in-the-wool anarchist, etc.). Their flat affect makes the jokes feel organic, the emotions fairly evoked.

Some critics have clucked their tongues at Isle of Dogs (which won the Headliners Award at last month’s SXSW) for “cultural appropriation,” which of course turns a blind eye (and deaf ear) to Anderson’s storied archness — almost always lacking in real-world textures, but instead forcing his stylized sensibilities on all his characters. Like Whit Stillman, characters in a Wes Anderson film — whether dogs, oceanographers or concierges — traffic in dialogue that feels crafted by hand and baked in a kiln, preserved, but delicate and precious. It’s not that he’s dissing Japanese culture, it’s that he imposes his worldview on every culture. It’s Wes Anderson’s universe, we merely live in it. And living in a universe with Isle of Dogs is a very positive thing. Good boy. Now playing at the Angelika Mockingbird Station.