Out choreographer Jamal Story takes to the heavens for Black History Month with aerial ballet for Dallas Black Dance Theatre

Out choreographer Jamal Story takes to the heavens for Black History Month with aerial ballet for Dallas Black Dance Theatre

ARNOLD WAYNE JONES

Executive Editor

jones@dallasvoice.com

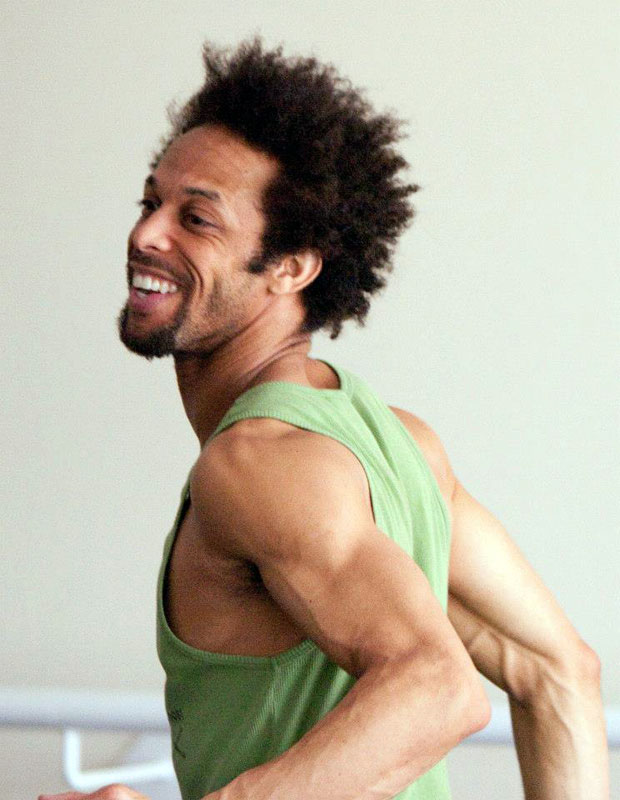

Jamal Story is the first to admit that, as a gay man in the dance world, he’s lucked out professionally. In addition to touring with Madonna as one of her dancers, he also serves as dance captain for Cher.

“Friends of mine say, ‘If you’d only worked for Janet [Jackson], you’d have the ultimate gay triumvirate. But Janet only hires female dancers,” Story laughs.

Getting to hang with two women who really helped define what Story calls “commercial dance” has been an honor and a revelation.

“Cher is exactly who you think she’ll be: Equal parts girly-girly and tough broad,” he says. “But she and Madonna couldn’t be more different, though both are extraordinarily hardworking individuals and have a high sense of attention to detail. They are clear to the inch what their representations need to be. That was wonderful for me [to learn from them].”

But as wonderful as that kind of success has been, where Story really feels at home isn’t on a huge stage, twerking and writhing for throngs of rabid fans (even though, he admits, “that energy is astounding”). As an artist, though, “commercial dance is totally different from what I do.”

Story’s passion has always been honoring the long tradition of dance pioneered by African-American artists from Alvin Ailey to Joan Myers Brown. And he wants to share that passion with the widest audience possible.

“There are five black dance companies in America that are over the age of 30 — all founded by black women artistic directors,” Story says. That elite club includes Dallas Black Dance Theatre, founded in 1976 by Ann Williams (she retired in 2014). “They are the ones with a specific black repertoire aimed at maintaining the works of black choreographers and black themes.”

This weekend, Story joins that repertoire. He’s one of the featured artists creating an original work for DBDT’s program called Cultural Awareness, a mini-festival mounted specifically for Black History Month.

“The cornerstone of the dance landscape [among these companies] is the tradition of preserving black dance in America,” Story says. “That includes a lot of the legendary ballets of Alvin Ailey, but in addition there is a large group of choreographers over the decades who have explored [that tradition]. I was trained under the aegis of that repertoire, and want to give audiences a window into that repertoire. I wanted to stay connected to that.”

“The cornerstone of the dance landscape [among these companies] is the tradition of preserving black dance in America,” Story says. “That includes a lot of the legendary ballets of Alvin Ailey, but in addition there is a large group of choreographers over the decades who have explored [that tradition]. I was trained under the aegis of that repertoire, and want to give audiences a window into that repertoire. I wanted to stay connected to that.”

Story’s affiliation with DBDT “has been a minute,” he jokes. He was an apprentice and guest artist while attending Southern Methodist University, then moved to Los Angeles where he continued to study black dance. So this program is something of a homecoming for Story, though he is excited to push some boundaries with his new piece, The Parts They Left Out, while still honoring the tradition of black dance.

“I don’t find it’s necessary to reach too far or hard to get to the energy of that black dance legacy — enough of it has been with me in my dancing for so long it’s there … it’s not something I consciously think of,” he says. But he’s elevating the level of work at DBDT… literally. His piece is almost entirely an aerial ballet. (He thinks it’s a first for the company.)

Training his dancers to move from terrestrial to ethereal dance presented a host of challenges.

FROM CHER TO ALVIN | Jamal Story choreographed an aerial ballet for DBDT’s Cultural Awareness program for Black History Month. (Photos courtesy Brian Gulliaux and Jamal Story)

“The first thing is getting over a sense of the height,” he explains. “I don’t have the dancers too high in the air — every apparatus is accessible from the ground. But there is the idea that you are not connected to terra firma. What that means on a technical level is, the skills you have with your

work on the floor is all compromised — you have a different sense of your body in space.” For example, on the ground an arabesque requires standing on one leg while the

second creates a perpendicular line. Since there’s no ground to push off of in the air, you have to rediscover that line. And you have to rely heavily on your upper body. “On the floor, it’s a lot about your legs, a connective sense of the instrument moving in space; dancing in the air requires extraordinary upper body strength,” he says. “Add to that aerial partnering, and you’re having to manage another body in the air.”

As technical as the work is, though, to Story it’s still secondary to the meaning. The Parts They Left Out it explores specific figures in

Greek mythology “with a little more fleshing-out of the stuff that gets left out in the oral tradition of [ancient history],” he says. “In most cultures, the oral testimony is very important at first, and then it’s written down. But it leaves lots of room for questions. My preoccupation was in the implication of Greek history and how it was comprised of brown people.” Looking into different theories on the origins of man and studies of mitochondrial DNA, Story says “it becomes clearer and clearer that the ancient Greeks were probably people of color and their myths would be part of our canon as well.”

And that, Story insists, is something everyone can be proud of.

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition February 19, 2016.