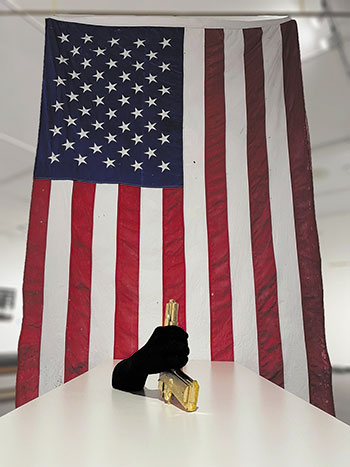

Bernardo Vallarino, Indecent Exposure, 2023, Mixed media, 24x24x30. $8500

Fort Worth artist Bernardo Vallarino doesn’t tell viewers what to think about his work; he invites you to decide himself

JAMES M. RUSSELL | Contributing Writer

James.Journo@gmail.com

Bernardo Vallarino doesn’t feel sleazy about placing a sculpture of a gun-shaped erect penis bulging out of incredibly tight boxer briefs alongside a commission for a synagogue’s 150th anniversary. In fact, there he is, on the third floor of the former location of the Arlington Museum of Art in December, looking at those works in the solo show Hard On: Guns, God and Gold, which includes photographs, paintings and sculptures.

Meaning and interpretation are open to discussion in his work, he stressed.

“I’m a pragmatist,” Vallarino said. It’s a genteel and Texas concept. He doesn’t want to offend; he wants to make people think, a skill he learned while studying art at his alma mater, Texas Woman’s University.

Bernardo Vallarino & Ariel Dais, El Martirio de Venus – Free to Carry. 120x60x72in, Mixed Media, $7200.

“The moment I realized I was a pragmatist is when I was forced to think in graduate school why I do the work that I do,” he said. Take, for example, his experience going through his art before pursuing his master’s degree in fine arts. His works then were about love. But he didn’t know why he was thinking about love.

Then he realized why: Love’s just a word. The action is what is important.

“I was pissed about the word ‘love,’” Vallarino said. It’s a strong but provocative statement, he explained, noting that “love” is a manipulative word that can be used for good or bad. But when love shines, “it’s in the moments that someone does something for someone else from a point of care,” he said.

Vallarino lives in Fort Worth with his husband, Curtis — who, to be clear, he loves. They are realtors, and Vallarino also serves as an adjunct professor at TWU, both jobs that he also loves.

Vallarino’s works included in the December exhibit span about a decade and vary in subject. But they share the gay Colombian-American’s desire to delve into the gray area between rhetoric and action, and how it can feed into cognitive dissonance. He critiques the violence we commit against each other, whether physically, socially or metaphorically. In that frame of mind, he specifically critiques the gaps between words and actions as well.

The same could be said of religion, where many people, especially LGBTQ people, would agree between faith and practice. He has a hard time being in-your-face with his criticism of religion, tapping instead into that pragmatic description.

“I didn’t want to be disrespectful. But there is a gap between theology versus practice,” he said, looking at Blind Faith (2015), a sculpture of a fly zapper hanging over a book. It’s amusing and dark. You hear the zap, and you see the zap of a religious text.

Among his most recent works is the far more sensitive commission for Emanu-El‘s 150th anniversary. Kaleidoscopes of Light, Habitat of Reflection was a “twist on a butterfly habitat with a human connection,” he said. Butterflies are common in his work. In Colombia, they are symbols of transformation.

It is, of course, a critique of religion, of why people can’t follow what they believe and act accordingly. “But I wanted to be mindful of the idea of ‘reflection’,” he said. He has a glimmer of hope for people, even if he is pissed about how we act.

So, he adapted a sacred Jewish text translated in English to “all life is sacred and must be protected, no human is inherently more important than another, and though we may look different from one another, the infinite nature of the Divine means that we are all equally created.” It is written on three mirrors covered in English, Sanskrit and Hebrew.

He’s spent the past 15 years thinking about guns, perhaps the most physical representation of violence. His newest work is the result of needing a psychological reprieve from that decade and a half.

“I’m not saying they’re wrong or bad, but instead I’m asking the question of what they are.

Bernardo Vallarino, La Plegaria, el Pensamiento y el Deseo de Paz Más Importantes – 2016, White Ribbon, Pin, Shadow Box. $450

“I’m now at a point where I can change from when I was looking atproblems such as people with guns,” Vallarino continued, even as his work shows some clear rage.

“Now I’m looking at how they interact with us now. Now I’m saying, ‘Let’s look at the problem without reacting to it.’”

Gay artists think about penises; Vallarino’s no different. But does thinking about a penis as a gay man inform his work?

He pushes back on the idea that his sexuality, like any other artist’s, informed what is a blatantly phallic symbol. With Indecent Exposure from 2023, the erotic gun-dick sculpture, the viewer can choose between whether it’s amusing or grotesque, or perhaps both.

“I tried hard not to apply my sexuality and to have queerness and sexuality central to the work, but they just so happen to overlap. There’s a sort of sensuality that comes with possession of a gun. And of course it’s a phallic figure. I’m approaching the gun as a symbol also of toxic masculinity,” he said, but with a strong and amusing strong visual figure.

“We’ve become desensitized by the violence of everyday life,” Vallarino said, and he wants to end the numbness, which is why he also sees something beautiful in it.

“I’m just wanting with my work to remind people, ‘don’t do this,” and to entice people to change people’s minds.”