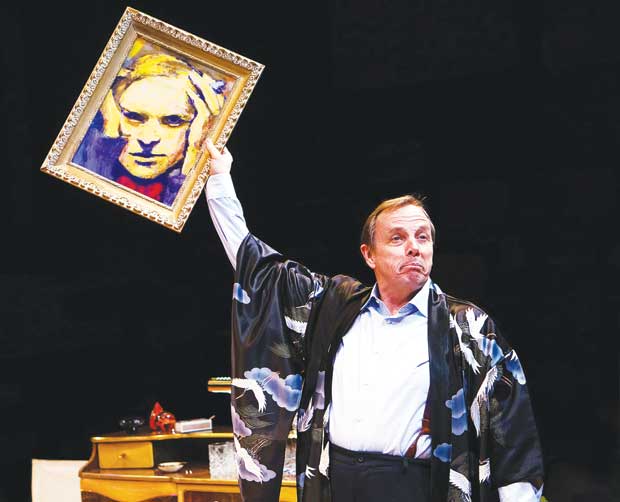

‘TRU’ STORIES | Jaston Williams, best known for his ‘Tuna’ roles, tackles one of the most iconic writers of the 20th century in his one-man show at Theatre 3.

Jaston Williams shelves the Tuna to portray Truman Capote, America’s most flamboyant man of letters

ARNOLD WAYNE JONES | Executive Editor

My life has been more biblical than I deserve,” Jaston Williams drawls from his home in Lockhart, Texas, demonstrating a scathing wit that has made him one of the true legends of Texas humor. With his professional partners Joe Sears and Ed Howard, Williams is co-creator of the Tuna Trilogy, a series of (now actually four) plays set in the third-smallest town in Texas, in which all the residents are portrayed by the same two actors.

But Williams’ cleverness — and talent — have always extended beyond those classics of Texana. He’s an experienced author, playwright, monologist and actor in others’ plays, as he’s about to show North Texas audiences (again) in his one-man show Tru, now playing at Theatre 3.

Williams’ own sense of humor serves him well in the show, about a few days in the life of Truman Capote, a towering figure in American letters who helped invent the modern style of journalism and reinvented the novel, but whose gifts were largely squandered to booze and bad behavior. It’s a plum role, and one not often performed.

Nevertheless, this isn’t the first time Williams has taken on the part, but which won its star, Robert Morse, a much-deserved Tony Award in 1990, which has been rarely revived in the years since — indeed, Williams was the first.

“I did it the first time more than a decade ago,” he explains. “[Dallas actor and director] Larry Randolph and I wanted to do something together and I talked to Jay Presson Allen, who was a big Tuna fan, and who wrote [Tru]. I contacted her agent who said she hadn’t released it to anybody, but she said, ‘I’d love for Jaston to do it!’ I think I was the first one outside of Bobby Morse on Broadway.”

Williams’ interpretation — and his insight into the man he’s portraying — has changed since the first time he mounted it.

“Back then we were much more aware of the humor of the play, but when we revived it back at Zach Scott Theatre [in Austin] a decade later, both of us had kind of grown into it. It’s also heartbreaking and scary. It’s really about a guy trying to get through a day without having a drink. I think that time around we truly nailed it.”

That was in 2013. Last winter, when Theatre 3 founder Jac Alder approached Williams about putting it on in Dallas, he jumped at the chance to reunite with Randolph, his good friend and former acting coach. But Randolph died last summer, and this third attempt has taken on a life of its own.

“This was Larry’s production, and we lost him, so we have been trying to recapture what he did,” Williams says thoughtfully. “We had all his blocking and intricate stuff and the folks at Theatre 3 have been very patient at letting me remember. I hope those who knew what a great artist he was will come see it, and see that his work has outlived him. It’s a very emotional thing for me because Larry was my acting teacher since I was 18.”

Williams sentiment for the show (and his friend) mirrors his own appreciation not just for Capote the man and literary lion, but for the period in culture he represented.

“He had such an amazing wit. It is so much fun to research him. I’ve read Answered Prayers and A Christmas Memory, as well as read the biography by Gerald Clark, which has such insights into [Capote]. There’s a wonderful section where [Tru] got into a big fight with Mary McCarthy not long after Breakfast at Tiffany’s came out. She said [something like], ‘Our literature has become the reflection of a mirror on a whore’s ceiling.’ Capote responded, ‘If anyone knows what a whore sees when she looks at the ceiling, it’s Mary McCarthy.’ That’s what I miss in the old days — these great literary feuds. We’ve gone from Dorothy Parker to Chelsea Handler and it’s not a fair trade.”

The play centers around the initial publication of stories from Answered Prayers, in which Capote dished about the highest levels of New York society, telling all the secrets his friends thought he would keep in confidence. The reaction against Capote at the time devastated him; one suicide was even directly attributed to his story. (The suicide victim “was one of those people who nobody missed but they hated to see her go anyway,” Williams says.)

Although he never met Capote, the two have an unusual personal connection. Capote famously wrote everything in longhand in a tiny, identifiable script. A few years ago, Williams was in a friend’s antique store in Lockhart and purchased a used book about Edie Sedgwick “for a few bucks. I got home and saw an inscription and I thought, ‘That looks like the signature is ‘Tru.’ I looked up the woman [it was inscribed to] and she was former editor of the Washington Post and it was indeed a gift from Capote.”

Such stories delight Williams, although he knows the author is not the pop culture figure he was in his heyday. For many, Capote is a vague figure (he died more than 30 years ago, and may be best known for Phillip Seymour Hoffman’s Oscar-winning portrayal of him). But those of a certain age will not soon forget his iconic presence: The fey mannerisms, the squeaky voice, the razor-honed one-liners emitting from a dwarfish figure on The Tonight Show and Dick Cavett. But how much of that do audiences need?

“I think you need some of those trappings,” Williams says. “To do the voice absolutely spot-on, he didn’t move his lips very much, which you need to do onstage. But you do your best to capture it as much as you can — the gesture, the many physical things — but at a certain point it’s about finding out where he is in his heart and soul.”

He was also one of the most flamboyant men of his day, unabashedly queer and in-your-face about it — something virtually unheard-of on the scale he was able to achieve.

“He was unbelievably honest about himself. He said, ‘This is who I am, how tall I am, how I move and talk and I’m not gonna change anything for anybody.’ And he always accepted who he was,” Williams says. “If you reached a certain degree of literary celebrity, the rules didn’t apply to you. Now you look in Hollywood and the tiny, tiny number of celebrities who have come out and shake your head. I look at the Oscars and think, ‘The only time there are more queens in California than during the Rose Parade is at the Oscars.’”

But, Williams laments, Capote was also “a sad genius. The Capote they played in Capote was at the beginning of his demise — he regressed, got fat, drank, got delusional and power-hungry. And yet he was never without his humor. And he always had a high opinion of his opinion.”

The role takes more out of Williams than many people might imagine — not the least of which is remembering 90 minutes worth of dialogue without ever having a scene partner.

“He was a heavy boozer. In between [the action] in Act 1 and 2 of Tru, he goes out drinking with Ava Gardner — you had to keep up with Ava! She was the gold standard of heavy drinkers. You think it is tough in the first act playing drunk, in the second act you have to play it with an ‘Ava Gardner hangover.’

“It’s a workout — vocally, physically and emotionally you go to depth of absolute heartbreak in this play,” he continues. “But I have this lovely sofa I use on the set that was in my apartment in New Orleans. When I do a matinee, I get a blanket and sleep for two hours, that’s the only way I can do it.”

Williams puts himself through all the trouble precisely because he thinks the message of Tru is something that needs retelling.

“I’m always hoping that younger audiences will come in and discover something about our world, and that contemporaries will come in and reconnect with something — the glamour and elegance that was that world,” he says. “It’s a step back — historically, musically, in terms of literature in terms of humor … and all with a bottle of vodka.”

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition January 9, 2015.