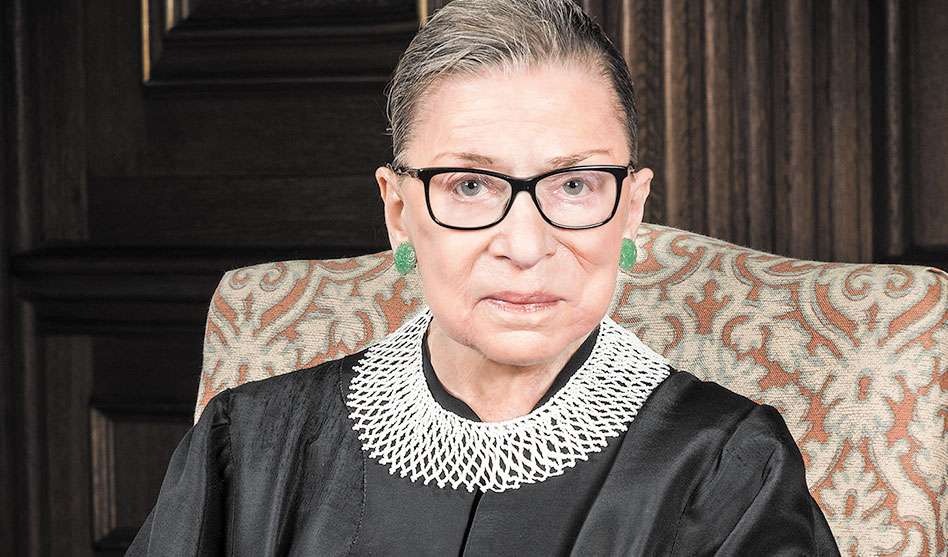

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg

True democracy demands that every American has the unobstructed right to vote

Kylee Reynolds and Shelly L. Skeen

Lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg understood the importance of one voice, one person’s lived experience and how one person can bring about radical change in support of full and lived equality for all.

Jeffrey Rosen, the president and CEO of the National Constitution Center, a non-profit organization chartered by Congress “to disseminate information about the U.S. Constitution on a nonpartisan basis,” said of Justice Ginsburg: “In battling illness, sexism and discrimination, she never allowed herself to be distracted from her path of creating what she called a more ‘embracive’ Constitution — one that embraced previously excluded groups, including women, people of color, immigrants and the LGBTQ community — not just grudgingly, as she put it, but with open arms.”

It was with those open arms that Justice Ginsburg brought her lived experience and her embracive philosophy to her work as a civil rights lawyer and to her opinions — and famous unapologetic dissents — as a Supreme Court Justice.

This legacy is because she knew what it felt like:

• to grow up as a Jewish person in a low-income, working class neighborhood during World War II, when Jewish people were being persecuted and murdered in Germany simply for being who they were.

• to suffer loss early in life when her mother died of cancer the day before she graduated from high school, a graduation she had to miss even though she was the valedictorian.

• to be demoted from her job with the Social Security Administration after she became pregnant.

• to be one of only nine women in the 1956 entering Harvard Law School class, that consisted of 500 mostly white men from wealthy families.

• to be the first female member of the Harvard Law Review and the first female member of the Columbia Law Review.

• to experience discrimination when she graduated at top of her class at Columbia Law School–only to learn that despite her hard work and success, no one would hire a woman, especially one who was also Jewish and a mother.

• to raise a family while going to law school, while at the same time taking care of her husband, who was battling a life-threatening illness.

• to take a job as a law school professor knowing that she was being paid less than her male colleagues simply because she was a woman.

• to start the Women’s Rights Project for the ACLU, at a time when abortion was not legal.

• to write the very first law school textbook on a new area of the law that she helped create — gender equality.

• to fight day in and day out for women’s rights as a litigator in a male-dominated profession.

• to win the rights for women to 1. have a job without being discriminated against based on sex; 2. have a bank account without the need to have a male co-signer; 3. be pregnant and still have the right work, and 4. sign a mortgage without the need for male co-signer.

• to win the rights for men to: 1. receive tax deductions for caring for dependents and 2. to receive social security survivor’s benefits if their wives died.

Because Justice Ginsburg experienced first-hand what it felt like to experience discrimination on so many levels and in so many situations, she also understood the importance how one person’s experiences can shape their perspectives and how that one single person can make a difference in the lives of many.

Justice Ginsburg, writing for the majority in an opinion that upheld the people’s right to choose their elected officials, quoted James Madison, “The genius of republican liberty seems to demand … not only that all power should be derived from the people, but that those entrusted with it should be kept in dependence on the people.” Whether we cast a vote or not, whether we participate in our local, state or national government or not and whether we like it or not, the people we elect as our representatives at the local, state and federal level and the judges who sit on our courts do speak for us. And in speaking for us, their decisions impact the most intimate and important aspects of our day-to-day lives and the lives of the people we love and care about.

This happens whether they share our perspectives and life experiences or not.

It is for this reason that Justice Ginsburg fought so hard to ensure that all Americans have the unobstructed ability to cast a ballot.

In her 28 years on the U.S. Supreme Court, Justice Ginsburg championed the unobstructed right of each of us to vote and to keep the three branches of government dependent upon our voices and perspectives. In her famous dissent in Shelby County v. Holder, (which earned her pop culture icon status as “Notorious RBG”), Justice Ginsburg, speaking to the majority that had just gutted a key provision of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, unapologetically explained that the unabridged right to vote is found in no less than five separate constitutional amendments and that each of those amendments gives Congress broad enforcement authority, because the right to vote is “preservative of all rights.”

She rebuked the majority for failing to consider the devastating impact their opinion would have on poor communities of color. Justice Ginsburg famously said that for the majority to determine that the key provisions of the act were no longer needed was “like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.”

As is clearly apparent now, Justice Ginsburg’s predictions about the impact of Shelby on the ability to cast a vote have come true many times over in the wake of 1. strict voter ID laws (at least three states enacted voter ID laws within 24 hours of the majority opinion, including Texas); 2. the purging of voter rolls; 3. racial and partisan gerrymandering; 4. the closing of polling places, and 5. voting lines that last for hours.

In one of her last dissents in support of the unobstructed right to vote, Justice Ginsburg again focused on lived experience of voters in Wisconsin, who were simply seeking to have their voices heard during the pandemic. After the majority refused to extend the deadline for absentee voting by six days, Ginsburg sounded the alarm, saying that the court’s “paramount concern” should be with the disenfranchisement of thousands of voters, and that the question was not “a narrow, technical” one like the majority suggested, but rather an important constitutional one.

She unequivocally stated that a meaningful vote was of the “utmost importance to the constitutional rights of Wisconsin’s citizens, the integrity of the state’s election process, and in this most extraordinary time, the health of the nation.”

Justice Ginsburg said, “Fight for the things that you care about, but do it in a way that will lead others to join you.”

One way we can all work for full and lived legal equality for all LGBTQ people, those who live with intersectional identities and those living with HIV is to follow Justice Ginsburg’s embracive philosophy and life-long legacy by raising our individual and collective voices, by casting our ballots, running for elected office and adding our voices and experiences to the conversation.

For more information on your right to vote and how to vote, contact Lambda Legal’s Help Desk, which is staffed by four full time attorneys, at LambdaLegal.org/HelpDesk. Founded in 1973, Lambda Legal is the oldest and largest national legal organization whose mission is to achieve full recognition of the civil rights of lesbians, gay men, bisexuals, transgender people and everyone living with HIV through impact litigation, education and public policy work. As a 501(c)3 nonprofit organization, Lambda Legal does not charge its clients for legal representation or advocacy, and Lambda Legal receives no government funding. Lambda Legal depends on contributions from supporters around the country.

Kylee Reynolds, Fair Courts Project Fellow, works out of Lambda Legal’s Washington, D.C., offices, and Shelly L. Skeen, senior attorney works out of Lambda Legal’s Dallas office.

The notorious RBG?

Thank you