Graduate program focused on creating better teachers in urban classrooms is reaching out to LGBT recruits

Emily Nolen, left, Terrance Smith, right

Tammye Nash | Managing Editor

At a time when the public education system appears to be at a crossroads, one organization is working to create career teachers who are better equipped to meet the challenges of teaching in urban schools. And recruiting LGBT teachers for its rigorous program is an integral part of reaching that goal, officials with Urban Teachers say.

Urban Teachers, previously known as Urban Teacher Center, was founded in 2009 to meet the challenge of improving the quality of new teachers. Founders Jennifer Green and Christina Hall, who were at the time colleagues in the Baltimore City

Schools central office, set out to create, from the ground up, a new “break the mold” program designed to “ensure every teacher would get the experiences and support they need to produce results with students,” according to the Urban Teacher website.

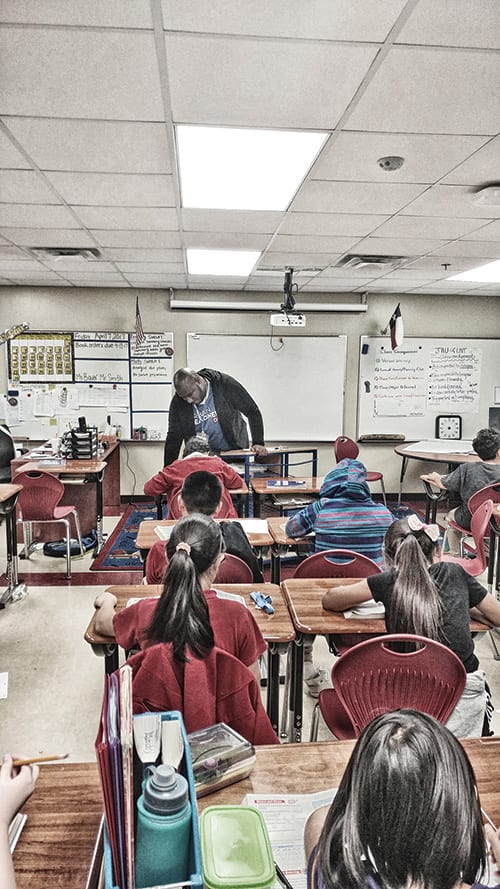

Terrance Smith in the classroom

They started with programs in Baltimore and Washington, D.C., cities with two of the highest-need school districts in the country. They expanded to the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex last July, and are looking to move into other cities soon.

Emily Nolen, executive director of Urban Teachers in DFW, explained that the organization is a four-year program that, in partnership with Johns Hopkins University, lets participants earn a master’s degree after two years and, after three years, certifications in specialty areas including English as a second language, special needs and math.

The burn-out rate among new teachers, especially those in urban schools, is alarmingly high, Nolen said. Young men and women fresh out of college “don’t really get enough training ahead of time” before stepping into the classroom, she said. Without that training, they often find themselves in situations where they fail. When they fail, they quit.

“We end up losing someone who could have been a really good teacher in the long run,” Nolen said. “If they had the right training, they would be successful. But they don’t, and because they care they aren’t willing to just do a crappy job with the kids. So they quit.”

Urban Teachers helps those young teachers avoid failure and burnout by helping them become better prepared for the challenges they will face in the classroom in urban districts.

Urban Teachers recruits spend their first year in a residency program, serving as co-teachers in urban classroom settings, with support from Urban Teachers faculty. “They work all day [in the classroom] and they are in graduate classes at night,” Nolen said. “The work is intense. We lose about 20 percent of our recruits in that first year. And that’s fine. We need to lose everyone we’re going to lose in those first months, because after that, they will be teaching their own classrooms and once you start, you can’t quit on the kids. That’s not fair.”

Nolen said that in looking to expand, Urban Teachers wanted an area with three components: districts that pay teachers a competitive salary, districts that pay for performance tied to achievement and broad community support for the schools. She said that it was support from the Dallas Regional Chamber and Commit to Dallas — a coalition of area nonprofits dedicated to helping Dallas students succeed — that sealed the deal.

“We felt like, in coming to Dallas, we were getting in a boat that was already going in the right direction,” she said.

The Urban Teachers program is not focused on education theory, Nolen said. “It’s designed to be different, to be relevant. It’s more much experiential, more clinical in nature. It is designed to teach them how to succeed in an actual classroom.”

While inclusion of LGBT people among its teachers is not included in Urban Teachers’ articulated, focused goal, Nolen said, the program strives for an inclusive environment that reflects the culture around it.

“Kids need to see teachers that look and feel and sound like them,” Nolen said, touting the fact that of the teachers in the Urban Teachers program, 70 percent are people of color, 35 percent are bilingual, 35 percent are male and 50 percent are first-generation college graduates.

While the program’s mission statement doesn’t specifically mention LGBT people, there is an LGBT affinity group, and LGBT participants are finding a welcoming home with Urban Teachers in DFW, thanks to the area’s large, well-organized and visible LGBT community.

Terrance Smith is from Orlando, and was at Pulse nightclub on June 12, when a gunman massacred 49 people and injured more than 50 others. That experience, he said, caused him to re-evaluate his life and set new goals for his future. Urban Teachers offered him a way to reach those goals.

Smith moved to Dallas and is now in his first year residency with the program.

“I wasn’t recruited because I am gay,” Smith said recently. “I’m not ‘the gay cohort.’ I am not identified that way, and nobody asks me to identify that way. I am just a cohort member who happens to be gay.”

This first year of residency, Smith said, “is a real gauntlet. But if you make it through this first year, then you know you are ready to move forward. It is giving me confidence.”

Urban Teachers is a tough program, but it’s worth it, Smith continued. “In general, I’d say, if you have a heart for children and you want to be a teacher, you should at least give it a try,” he said. It’s good for LGBT people who want to be teachers, and it’s good for LGBT youth trying to make their way through school.

“Like Emily said, it’s good for kids to see teachers who are like them who have been able to succeed,” Smith continued. “A cisgender, heterosexual teacher wouldn’t really be able to relate to a student battling to find their own identity [as an LGBT person].

“We need more openly [LGBT] teachers who know what it’s actually like to sit up at night, trying to figure out why you are feeling the way you do.

“As a gay teacher, I can say to those students who might be struggling [with sexual orientation or gender identity issues] that there really is a light at the end of the tunnel,” Smith said.

Of course, at the end of the day, Nolen said, the goal is to train teachers to be better and more effective teachers.

“As much as we value a diverse cohort, and as much as we value the ability of that diverse cohort to reach a diverse student population, the main goal is to create highly-skilled educators,” Nolen said. “In the end, we’re not going to love kids to college. In the end, if our teachers can’t effectively teach their students, then we’re failing. And we aren’t going to fail.”

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition April 14, 2017.