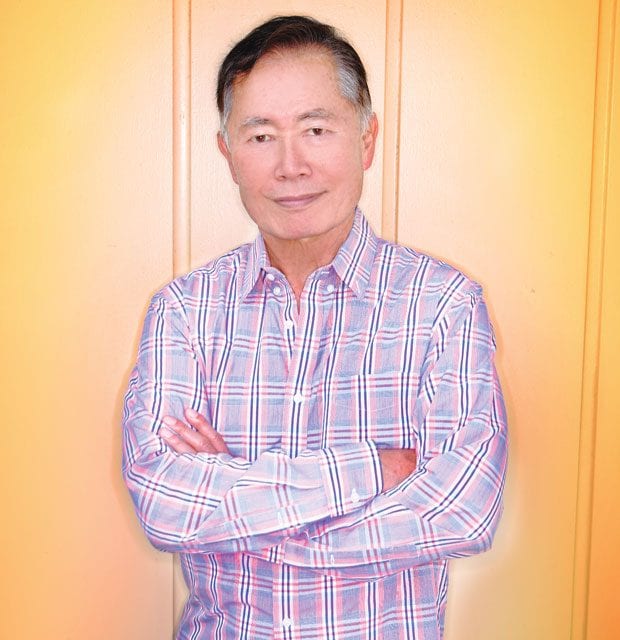

The out Star Trek actor and his family spent several years detained in a tar paper shack before he found success on television

As a child, George Takei began class each day by reciting the Pledge of Allegiance, which included the words, “with liberty and justice for all.” They were hollow words, falling on the schoolroom’s bare plank floor in the Arkansas internment camp where his family had been placed during World War II.

Shortly after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, the federal government created legislation that stripped Americans of Japanese descent of their homes and businesses and put them in tar paper shacks throughout the country. No Germans or Italians were rounded up, although we also were at war with those countries. The Japanese population in Hawaii was left alone, as were those of Japanese descent on the East Coast and in the Midwest.

Takei explained that about 40 percent of Hawaii’s population was of Japanese descent, and the islands’ economy would have collapsed had they all been removed. On the West Coast, however, anyone with 1/8 Japanese blood was arrested and carted off to the numerous bleak internment camps.

“They even raided orphanages,” Takei said. How could a 6-month-old baby threaten the safety of the country, he wondered. Takei called the round up a completely irrational, racist act. His family had about two weeks’ notice that they would be taken into custody.

“I remember that day,” he said.

He was 5.

“My mother got us up early,” he said. “Tears were streaming down her cheeks.”

Forced at gunpoint from their house, the Takeis were moved into a horse stall that still smelled of manure at Santa Anita Park, where they would be housed while the internment camps were being built.

“It was a degrading and humiliating experience,” he said.

A few months later, Takei’s family was moved to a camp built in the swamps of Arkansas. The family lived through the war surrounded by barbed wire and guard towers, “with machine guns pointed at us,” he said.

But Takei’s bitter memories of this period are colored with his keen sense of humor.

“A search light followed me at night to the latrines,” he said.

He remembers that searchlight fondly, thinking how nice of them to light the way for him to go pee.

Some of the older children in the camp told Takei that if he wanted something, he could approach the guards at the fence and ask for it, but he had to say the magic words and say them very fast. The words were the Japanese word for fish, sakana, and beach. So he approached the guards who were smoking at the foot of one of the towers and said, “tricycle” and “bubble gum” and added the magic words “sakana beach,” which sounds like son of a bitch when said quickly.

After the war, the Japanese internees were allowed to leave the camps. Each was given a bus ticket to anywhere in the U.S. and $20.

Takei’s father headed back to Los Angeles, where they were from. He found a house on skid row and a job as a dishwasher. The family didn’t follow until February 1946.

He described that apartment as horrible and the neighborhood as frightening. His teacher called him derogatory names.

But the family only stayed there a short time before his father bought a dry cleaning business in a Mexican neighborhood in East L.A., where he felt safe among warm and welcoming neighbors.

“Mrs. Takei made the best enchiladas,” he said.

Less than 20 years later, Takei was starring in one of the most enduring shows on television. The original Star Trek was always optimistic. Sex, race and national origin were either irrelevant or added a layer of richness. Racism was attacked head on in a number of episodes.

Takei’s Sulu was the first recurring mainstream Asian TV character not portraying “the enemy.” About the only thing missing from the original series was a gay character. Around the set, Takei said the other actors knew he was gay. He remembered one time sitting in a make up chair next to Walter Koenig who played Chekov. A particularly hot extra in a very tight shirt was behind them, and Koenig motioned so Takei would notice.

“My Star Trek colleagues knew,” he said.

But no one would have outed him.

“They didn’t want to be responsible for destroying my career,” he said.

Years later, Koenig served as best man at Takei’s wedding to longtime partner Brad Altman. They’ve been together for 26 years.

Takei said he knew he was gay from the time he was a child, but he didn’t come out publicly until former Calif. Gov. Arnold

Schwartzenegger vetoed a marriage equality bill in 2005.

So while he described himself as “very closeted,” he said he was “quietly out for a long time.”

Today, Takei remains quite busy. Over the past year he’s appeared on Lost Girl, The Simpsons, The Neighbors, Hawaii Five-0 and The

New Normal. Almost 6 million people follow his daily Facebook posts. He’s also working on a musical called Allegiance, based on his experiences in the internment camp, that’s headed to Broadway.

This week, Dallas Comic & Pop Expo welcomes George Takei to a signing at Madness Games & Comics, 3000 Custer Road Suite 310, Plano on Jan. 3 from 6–8 p.m.

On Jan. 4, Takei will perform with the Fort Worth Symphony. He’ll narrate as the orchestra performs music from a variety of science fiction films including Star Wars, Close Encounters and, of course, Star Trek.

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition January 3, 2014.