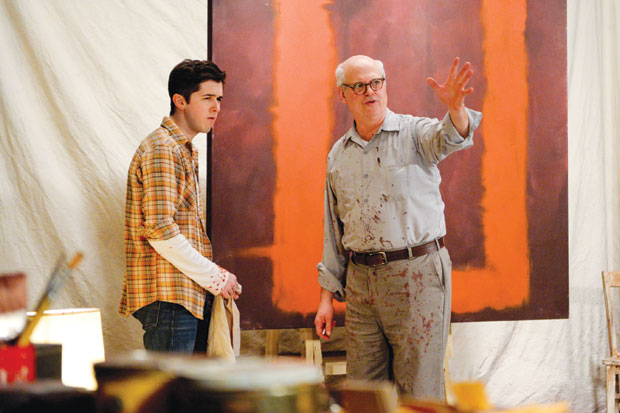

Before the action of Red begins, the play has begun: As the audience files in, Mark Rothko (Kieran Connolly) is seated in front of his latest canvas, contemplating it. To him, this is as much painting as the act of putting pigment to surface.

If you can’t accept that, you might find Red heady and dense; but it’s easy to accept with playwright John Logan’s brisk dialogue and sharply delineated portraits of a giant of modernist art and his fresh assistant Ken (Jordan Brodess, protean and with the goofy good looks of a 1950s matinee idol). For 90 minutes, they argue about what art means, how it affects us and what it takes to create it — for Rothko, at least, each creation is a form of destruction, as he undermines the masters who came before him.

Red is a fun play, one that revels in its intellectualism even as it challenges its characters to get outside their heads, to “become human,” as Rothko demands.

Too bad the artist himself is so deficient there. Logan subtly embeds references to Pygmalion/My Fair Lady is his script (lots of talk about “divine spark” and Ken finally becoming someone worth noticing). It’s a mentor/protege story, told with wisdom and high expectations of its audience’s ability to follow names and themes, though it resists folding, origami-like, in on itself — you can appreciate its points even if you don’t care too much about modern art (though it never hurts).

Surprisingly, though, the emotional focus of this production is Brodess, a resourceful, nimble actor who moves on his feet like a boxer: Full of energy but also purpose. With him, Ken never seems like a dilettante (think Anne Hathaway self-important nobody in The Devil Wears Prada) but a sponge soaking up as much as he can. As much can’t be said about Connolly, who seems curmudgeonly as Rothko but not imperious; his interpretation is more annoying than intimidating — Archie Bunker, not Henry Higgins. But even his bad choices don’t diminish the intimate smartness of this idyll on humanity and art.

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition February 22, 2013.