Pride time: Histories of Stonewall, gay activism, Woodstock inform readers young and old; plus a language lesson

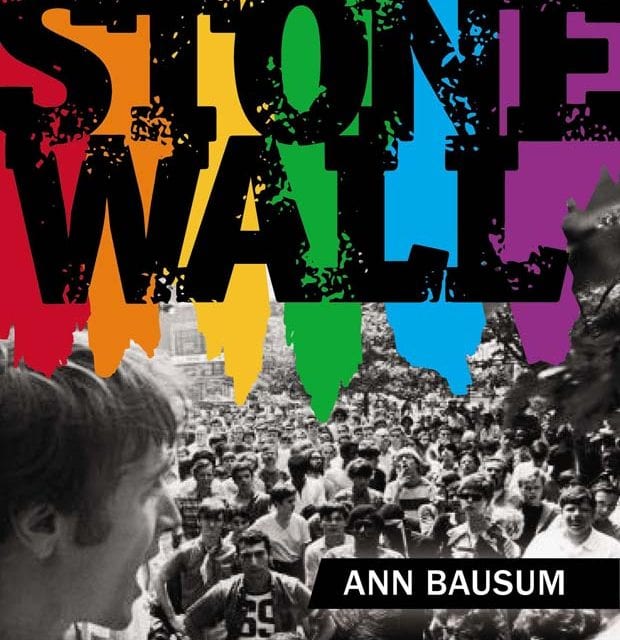

Stonewall: Breaking Out in the Fight for Gay Rights by Ann Bausum (Viking 2015) $17; 120 pp.

Your favorite hangout may not be all that fancy, but you’ve got places to sit, flat surfaces for your stuff and your friends are always around. Best of all, nobody says you can’t be there; everybody’s welcome all the time. It wasn’t always that way, though, as we learn in Stonewall: Breaking Out in the Fight for Gay Rights.

There was a full moon that night, and it was hot — not hot like you’d describe a person, but “beastly hot,” weather-wise — and it was hotter still inside New York City’s Stonewall Inn.

For years, it had been illegal in many cities to dance with someone of the same sex. With a few rare exceptions, being gay could get you fired from work, rejected by family and generally ostracized; if you were a man wearing women’s clothing, you could be arrested immediately. But the Stonewall Inn allowed dancing, drinking and cross-dressing, and the police usually looked the other way because, says Bausum, the Mafia had ties to the Stonewall and bribes kept things running.

By June 1969, this covert freedom started causing problems: “closeted homosexuals” involved in an international bond scandal were spotted at the Stonewall by “organized crime operatives” with blackmail on their minds. The New York police department was ordered to close down the Stonewall. In the hot early morning hours of June 28, they raided the packed bar.

It didn’t go well. As partiers and staff were arrested, a crowd began to form to taunt police — and it grew as people ran to pay phones to call friends. Some of those arrested were freed; others were roughly handled. Bausum says that one of the latter, a lesbian, asked the crowd if they were going to do anything about it; they did.

At first, pocket change rained down on the police, then pebbles, stones, bottles, and burning containers. Some of the officers took refuge inside the bar, awaiting backup that didn’t arrive for nearly an hour as two thousand people raged on the streets. Riot crews eventually showed up, and were mocked.

The unrest, says Bausum, lasted several nights — but what lasted longer was that lesbians and gay men suddenly knew that they weren’t alone.

Although it can become florid for the sake of drama, Stonewall is a surprising book filled with history that younger people may not know.

The surprise comes in what Bausum shares, which seems tame by today’s news, perhaps even quaint: nobody was seriously hurt, and the single death was accidental and barely related. That almost made me afraid readers might forget that the riot marked the coalescence of activism for gay rights, but Bausum anecdotally reminds us repeatedly of Stonewall’s importance. She then goes on to look at activism at other times in LGBT history.

This book is meant for teen readers ages 12 and up, but it might be a challenge for those on the younger end and it certainly can be enjoyed by adults unfamiliar with this event. If that’s you, then Stonewall is rock-solid.

The Right Side of History: 100 Years of LGBTQI Activism by Adrian Brooks (Cleis Press 2015) $19; 243 pp.

This summer’s Pride Parades were raucous events. And why not? There’s plenty to celebrate: new laws, old friends, and a sense of better — which can make it hard to remember that “such gains didn’t occur in a vacuum,” as Adrian Brooks notes in The Right Side of History, “a chorus of voices untamed” that collectively offers an explanation.

To begin, Brooks writes of Isadora Duncan, a free spirit who, when ladies were expected to be proper, danced on-stage with abandon, bared her breasts in public, and slept with whomever she pleased — male or female.

Hayden L. Mora writes of gay life in the early 20th century, when clubs for “same-sex attraction” began to appear in larger cities, though being caught in a compromising situation then could result in a loss of citizenship. For Henry Gerber, the choice was mental institution or U.S. Army; he picked the latter and came back from World War I, “determined to begin organizing gay men.”

The father of the gay liberation movement and founder of the Mattachine Society got his fire from another organization’s strike. A well-liked gay African-American boy, lovingly called “Pinhead” as a child, grew up to be Martin Luther King Jr.’s “right-hand man,” while a nerdy white doctor (who happened to sleep with men) changed our notions of male sexuality. Activists today fight for intersex infants, asking doctors to delay sex-assignment surgery. Conversation launched a lesbian organization, and people have stepped into activism roles because of Anita Bryant, out-of-the-closet writers, politics, personal discoveries and a 54-ton quilt.

And that parade you marched in? If you lived in San Francisco, you might like to know that Pride Parade routes are exactly the same as a funeral march walked by strikers and their families in 1934.

Lately, it seems as though I’ve been seeing a plethora of books on Stonewall — including one in this column … as if that one event is where LGBTQI activism began. It’s not, of course, and The Right Side of History proves that.

Though it’s far from definitive, Brooks’ collection informs and inspires readers who likewise want to make change or to know where change came from. I liked browsing the short biographies here, but I noticed one quirk: some of the profiles seemed to be a reach. Yes, they were very interesting, and yes, they were about people who stood their ground, but were they LGBTQI activists? Perhaps not always.

Even so, what you’ll read here may make you want to do something. At the very least, it’ll give you understanding for those who paved the way. And if that’s information you need, then find The Right Side of History… and just start it.

After Woodstock by Elliot Tiber (Square One Publishers 2015) $25; 462 pp.

Though their decision to purchase and operate a run-down motel in upstate New York was a disaster from the beginning, Elliot Tiber’s parents refused to give up the “shambles of a resort” they’d dreamed of owning. Tiber, a dutiful Jewish son, “had been sucked into this black hole” 14 years earlier, and he was stuck now.

But in the summer of ’69, something “just short of a miracle” happened: Woodstock. For more than a week, the motel was full of guests (at $750 a night) and when it was over, the hippies were gone, the mud was cleaned up and the family was flush with cash.

Seizing opportunity, Tiber took his share and left “my largely miserable past behind.” He bought a new Cadillac and headed for Los Angeles, where two friends had invited him to live with them in exchange for decorating an old mansion they’d bought. Tiber was also excited to see the Hollywood sign: “the letters weren’t exactly straight; well, neither was I.”

Months after arriving, though, it was apparent that California wasn’t the place he ought to be. Tiber’s father was dying, so Tiber returned to New York, mourned his father, fought with his mother, sold the motel for her, and fell in love with a Belgian student who had to return home after his studies were done. Months later, Tiber followed André to Europe, learned French, and started writing in earnest: TV skits, movie scripts, and memoirs.

But true love never runs smoothly, of course, and though they enjoyed dancing at leather clubs together, André started going alone. Tiber never knew exactly what André was doing but he had his suspicions, and since a “gay disease” was rumored to be circulating, Tiber was concerned…

After reading After Woodstock, I think you’ll agree that Tiber is the Forrest Gump of gay memoirs. He has done it all: organized Woodstock, crossed the Mafia, hobnobbed with celebs, made movies, appeared on TV … the list goes on. It’s almost exhausting — maybe because this book could have easily been two books: Tiber packs a lot — an awful lot — into this memoir, which can be overwhelming. Yes, he’s got a wicked funny bone, and yes, this is an appealing look at gay life from the Stonewall years forward, but it can be too much. While I didn’t not like this book, there were times when I needed a break from that frenzy.

I think stop-and-go readers will be able to get past the rompishness of this tale, and biography lovers will easily be able to ignore it. If, in fact, you like a little madness with your memoir, find After Woodstock and you’ll have it all.

Holy Cow! by Boze Hadleigh (Skyhorse Publishing 2015) $14.99; 303 pp.

No doubt about it, humans love our animals. We love them so much that we sprinkle references to them in our daily conversation, mostly without even thinking about it. Our shaggy dog stories are sometimes just that — but where did those old sayings, clichés, discouraging words and tender nicknames come from? The truth, as Boze Hadleigh shows in his new book Holy Cow!, is an interesting, yet convoluted, tale.

In many cases, animalistic words came about as description: Oxford, England, for instance, was once a place where oxen forded a river. Tell someone there’s a dogleg in the road, and they’ll know what you’re saying — plus, a road like that might make them sick as a dog.

And then there are the words that really make you scratch your head: Great Britain’s hedgehog pudding isn’t made of the spiny mammals, and dogs and monkeys are much more likely to ape you than is a copycat. And about that famed cat curiosity? It might’ve been targeted at another type of animal.

Let’s say somebody’s made you mad. Calling him a dog goes back many years, perhaps back into the mid-1800s when “the only good dog was a useful dog.” “Bitch” has always been directed at women; its first near-appearance in film was in 1939, and that was pretty scandalous. Call someone a rat and, well, that’s self-explanatory. The modern street use of the word “heifer” is pretty wrong, unless you’re in a barn.

There really is more than one way to skin a cat (catfish, that is). A sawhorse and a clotheshorse are similar in origin. And if you think a kitty really has nine lives, well doggone it, you’re barking up the wrong tree.

Ahh, language lovers. I can practically hear you howling for this book now — and for good reason. Like a dog with a bone, you won’t want to let Holy Cow! go.

Starting with canines and ending with birds, bees, and bugs, Boze Hadleigh — an openly gay chronicler of pop culture, who has also written about gay portrayals in film and music — goes whole hog in explaining where many of our favorite expressions originated. But this book isn’t just horseplay — he includes words that are archaic (but need resurrection), as well as localisms and words you’ll want to add to your vocabulary. That all adds up to fun that’s useful and, for dyed-in-the-wool linguists, it’s a golden egg.

So let’s talk turkey: if it’s been a coon’s age since you last read a book about language, it’s time you find this one. You won’t sound hackneyed or feel like a dinosaur with Holy Cow! This book is the cat’s meow.

— Terri Schlichenmeyer

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition September 18, 2015.