Clark Williams

Criminologist heads to Dallas to investigate gay Ennis man’s 1994 murder

CAROLINE SAVOIE | Contributing Writer

CaroSavoWrites@gmail.com

A retired social worker turned criminologist is on his way to Dallas this month to find answers for a family whose relative, a gay Ennis man, was found bound and slashed to death in an Irving field in June 1994.

Clark Williams, a gay Wisconsin native who now lives in Los Angeles, said he never intended on working in criminology — at least, not until his daughter moved off to college, and he found himself with ample time on his hands.

He learned about a filmmaker who was working on a documentary about the 1990 homicide of William “Billy” Newton in West Hollywood. The filmmaker, Rachel Mason, had new information that would implicate Milwaukee serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer in the murder. But Williams had grown up alongside Dahmer in Wisconsin, and he knew he had information that would disavow her lead.

After that, “In a strange twist of kismet, I found myself looking into the Newton case myself,” Williams said.

He worked closely with the Los Angeles Police Department and many of Newton’s friends, tracking Newton’s movements across the country before his death. As a gay man who lived in Milwaukee at the same time as Newton, Williams found himself enthralled by Newton’s life, and, through his own investigative work, he uncovered a previously unknown person of interest in the case who had lived in Dallas in the 1980s and was, at the time of Williams’ investigation, in jail in Oklahoma for an unrelated offense.

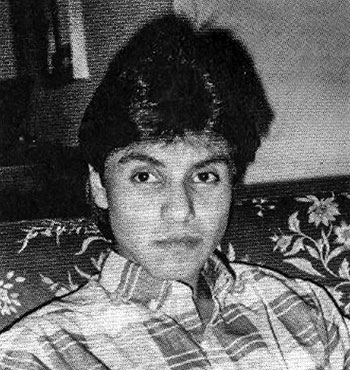

Paul Quintanillo Jr.

“After developing a detailed suspectology on this new witness and handing the lead over to the LAPD investigators, the homicide detectives flew to Oklahoma to interview the suspect, a former gay porn model and trans white supremacist named Darrell Lynn Madden,” Williams said.

During the interview, Williams said Madden confessed to Newton’s murder and is largely believed to have been a serial killer operating at various times in California, Texas and Oklahoma. The dramatic revelations in this case, known in Los Angeles as the “gay Black Dahlia” murder, led to a front page Los Angeles Times article and national media attention focusing on Williams.

“Overnight, it seemed, my quiet life as a retired social worker and empty nester suddenly changed,” Williams said.

Once the Newton case was solved, Williams started volunteering his time to help the LAPD, a variety of other law enforcement agencies and the families of murder victims uncover information that could generate new leads in old cases for law enforcement.

Williams is now investigating a cold case from 1994 in Irving — that of a gay man from Ennis named Leopoldo “Paul” Quintanilla Jr. who was last seen alive at a bar on Cedar Springs called Big Daddy’s before being found bound and slashed to death in a field in Irving. Quintanilla died on June 22, 1994.

“As Paul, Billy and I came of age as gay men during the same period, I began to feel this remarkable kinship with Paul’s life and story,” Williams said. “In my view, this cold case investigation has gone awry, and I believe that Paul Quintanilla deserves justice.”

Williams said his investigative process starts with finding anyone who knew the victim and then studying the social and political climate at the time, especially when the victims are queer.

“I have to time travel to learn everything I can about the days before and after the crime,” he said. “I want to go back and look for news reports from the week of the murder and see what was happening, like were there any triggering events? Why [was he murdered] that week versus another week?”

Williams found that Quintanilla was murdered days before the Stonewall Riots’ 25th anniversary. He said he was familiar with the bars in Oak Lawn after studying Madden’s life in the 1980s, and he found an ad in the Dallas Voice, archived in the University of North Texas Digital Library. That ad was promoting an event at Big Daddy’s the night that Quintanilla was murdered.

“And so I looked at that and went, ‘Wow! Could that have been a triggering event for someone who wanted to commit harm against gay people?’” Williams said.

“While we see that as a celebration of our community, it’s just antagonizing for someone who hates gay people, to see the celebration of our people.

“That’s something that just was never even considered in Paul’s murder investigation, that he could have been a victim of a hate crime. Because there were so many hate crimes being committed in Dallas at the time.”

Williams said that when he comes up with a theory, he’s “agnostic” to it. He doesn’t want to build evidence around a theory, but instead, lets the evidence speak for itself.

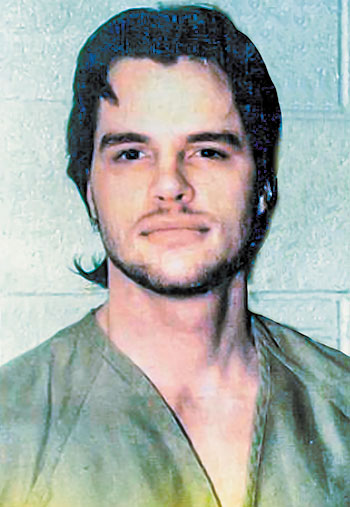

Aaron Christopher Foust

He said he’s been looking for gay men who were in the area where Quintanilla was last seen in 1994, but he’s run into a problem: Many gay men died of AIDS during that time. He said he had the same problem in researching Newton’s case: since Newton was a gay porn actor, many, if not most, of his colleagues had died by the time Williams was looking for answers.

Williams said he’s been working on Quintanilla’s case for nearly two months, and he’s already found a person of interest. That person is Aaron Christopher Foust.

Foust was arrested in 1997 for killing a gay man named David Ward in Fort Worth; he was convicted in April 1998 and sentenced to death. It was, Williams said, a brutal murder, and he has found similarities between Foust and Madden, Newton’s killer. He said Foust was a psychopath from an early age, and his father spoke in a documentary about being frightened of his son.

“Before Aaron’s execution in 1999, his father asked him if he had killed before, and Aaron said yes,” Williams said. “From what I can tell, that wasn’t ever investigated.”

Tammye Nash, then a reporter for Dallas Voice and now the newspaper’s managing editor, interviewed Foust at the Tarrant County Jail in 1996, before Foust was transferred to state prison. She told Williams that when she asked Foust if he killed David Ward because he was gay, Foust replied, “If he was straight, I wouldn’t have killed him.”

“So he has a propensity to kill, and he was living in the area in May 1994,” Williams said.

He said Quintanilla lived in Dallas until November 1993, when he moved home to live with his parents in Ennis. Then the young man drove up to Dallas on a Monday night and never returned. He was found in a field in Irving, stabbed hundreds of times, a victim of overkill.

“He died of head injuries and slashing of the neck,” Williams said. “This was a hateful crime. From what I’ve learned, Paul was a lovely person, not someone who would engender this kind of hate. Someone hated who he was or what he represented.”

Williams said he believes the case ran cold when police said Quintanilla did drugs. “It affected the investigation,” he said. “The police saw him differently. A lot of people were using drugs. That doesn’t mean that he deserved to be a victim of homicide.”

Williams said cases involving the most vulnerable people in society — sex workers, people without homes and LGBTQ people — are the cases that draw him in.

“Sadly, some of these victims’ lives have been overlooked with the passage of time. But I do know that their families and friends have never forgotten about what happened to their loved ones,” Williams said. “That is why I want to use my skills to generate new interest in the investigation and, hopefully, provide new leads for law enforcement investigators.”

Williams is traveling to DFW to continue his investigation “on the ground” in late April and early May. He plans to spend time in Ennis to learn as much as possible about Quintanilla’s childhood, adolescence and family life. He also plans to visit the crime scenes in the Oak Lawn area and the Irving field where Paul’s remains were found, to pay a visit to Quintanilla’s surviving family who now live in Sherman, and, hopefully, to arrange a meeting with the lead homicide detective assigned to this case.

Anyone who knew Paul Quintanilla Jr. or Aaron Foust or who may have information pertaining to this case and is willing to speak with Williams can contact him by emailing editor@dallasvoice.com.

Wonder if this man could take a look at the Alan White case? Seems to have been sort of forgotten.