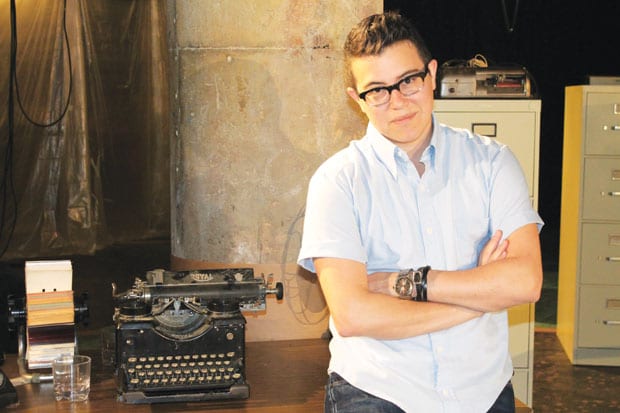

Trans playwright Sylvan Oswald looks inside himself for his world premiere play ‘Profanity’

OSWALD IN DALLAS | Sylvan Oswald on the set of Undermain Theatre’s premiere of his new play, set in a 1950s real estate office. (Arnold Wayne Jones/ Dallas Voice)

MARK LOWRY | Special Contributor

marklowry@theaterjones.com

Sylvan Oswald never set out to write plays telling his story — even as teachers, mentors and conventional wisdom repeated that mantra of writing “your” story. Whenever he heard that, he wanted to reply, “Can I write a play about these people?” By that, he meant not making it about him, but about the characters occupying his head for years — some of them, admittedly, inspired by his own family.

Sylvan Oswald never set out to write plays telling his story — even as teachers, mentors and conventional wisdom repeated that mantra of writing “your” story. Whenever he heard that, he wanted to reply, “Can I write a play about these people?” By that, he meant not making it about him, but about the characters occupying his head for years — some of them, admittedly, inspired by his own family.

But art has a funny way of surprising folks — even its creators.

“There’s this way that my plays know more than I do,” observes Oswald, whose play Profanity, about 1950s real estate agents selling property that doesn’t exist, receives its world premiere at Undermain Theatre. “They knew more about me before I could articulate it.”

Born a female in Philadelphia to a Reconstructionist Jewish father (the second of four half-siblings), Oswald’s process of articulating his journey as a transgender playwright — that’s a fairly recent self-billing — has emerged organically, discovering more about his identity as a writer and a non-cisgendered person (i.e., not identifying with the gender he was born to biologically) as he went along. As with any artist — any human — both of those explorations are ongoing.

As a kid, Oswald was not into sports or other children’s games; instead, he wrote “little skits” and drew them out with crayons. In junior high school, a local playwriting organization offered several workshops, and Oswald discovered that there was a type of writing that didn’t involve long sentences and paragraphs. By the time he’d reached high school, he was directing plays for his own theater group, had written a paper on Sam Shepard and discovered the book that would change his thinking about theater-making: Games for Actors and Non-Actors by Brazilian writer and theorist Augusto Boal, also known for his Theatre of the Oppressed. On reading that, Oswald describes his reaction by making the sound, accompanied by hand gestures, of a bomb exploding.

As a theater major in college, a writing spree spurred by a serious case of unrequited love during a study-abroad trip led to an introduction, from a mentor, to the work of writers like Mac Wellman and Suzan-Lori Parks. That’s when Oswald realized he wasn’t alone in the way he put thoughts and words together — and his desire to shun traditional dramatic structures. He also discovered something about the power of writing, and how it mirrored personal questions.

“I realized that I could write about stuff that wasn’t being talked about,” says the baby-faced Oswald, who dresses in the button-downed casualness of a prep school senior on spring break. “I started writing roles about girls that play boys, and I was working some stuff out. … I had been writing these females playing men and calling them ‘pants roles,’” he says. “One of my mentors said, ‘What are you doing with these pants roles — you’re not revealing them, so why are they there?’”

He pauses.

“I was not ready to answer that question,” he says. “I was discovering that in myself.”

When he realized that these roles were basically transgender characters, Oswald wrote his inaugural play with specific trans characters, Pony. That’s the premier play in his first trilogy (which also includes Vendetta Chrome and Painful Adventures). Profanity is the final work of his second trilogy, dealing with “cosmic mysteries” (it’s preceded by Sun Ra, about the famed jazz musician, and Nightlands, inspired by his maternal grandmother).

Gender identity has always been a theme in his work, even as he has tried on different labels about his sexual orientation. “[The word] ‘lesbian’ always felt like second-wave feminism for me, and that wasn’t helped by the problem of not feeling very female,” he says. “It was not until the word ‘queer’ started to crest [that I realized] it was that.”

Profanity is interesting in that it’s his first play with all cisgendered characters. Inspired by uncles on his mother’s side — who sold homes in Philadelphia’s Logan area, where houses were built on unstable soil, leading to a literal housing collapse — the Undermain production features Bruce DuBose, Michael Federico and Alex Organ. With its real estate theme, it invites comparison to David Mamet’s Glengarry Glen Ross; but where that play uses testosterone as competitive fuel, Profanity explores a bigger issue of defining masculinity.

“My experience is like a sidebar to this play,” Oswald says. “Sometimes I’m writing my story and these are real questions I have, too.”

No doubt, those questions will continue to be explored in his work, which includes an upcoming web series — his own version of a “transition video,” which he filmed and describes as a “low-fi, mock-doc, semi-improvised web series about two trans guys making a web series.”

Art and life, imitating each other, regardless of pronoun.

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition September 13, 2013.