Staff and cast members from Pulse talk about the night of the shooting, and how they are reclaiming their lives

Tammye Nash | Managing Editor

It’s been less than two months since a lone gunman walked into an Orlando gay nightclub called Pulse right at closing time and opened fire with a semi-automatic rifle and a 9mm handgun, killing 49 people and injuring 53 more.

For the general public, the horror of what is the deadliest mass shooting in modern U.S. history may have begun to fade. The LGBT community it remains ever-present, but perhaps at least a little less urgent.

But for those who were there, the horror and the fear remain as strong as ever.

This past week, six staff and cast members from Pulse were in Dallas, brought in as special guests to perform during the Miss Gay USofA Newcomer pageant at the Round-Up Saloon. Such a trip has become common for the club’s employees, they said; clubs around the country have been inviting them to come to perform, to participate in fundraising events, because the club remains closed and the staff remains without work.

The six — manager A’zsia Dupree and performers/staff members Angelica Sanchez, MrMs Adrien, Axel Andrews and Kaija Adonis, along with Angelica’s roommate and former Pulse cast member Chevelle Brooks — sat down with Dallas Voice on Wednesday afternoon to talk about the night of the attack and the days since.

Even now, they all agreed, at least parts of what happened that night remain fuzzy in their minds.

For A’zsia, it was just like any other night at work. “We had stopped serving liquor, and I was making my rounds,” talking to the bartenders, making sure they were closing out all the open tabs, getting ready to close out their registers. She had just made her way to the dressing room when the shooting started.

“I was right there by the back gate, but it was locked,” A’zsia said. “At first we thought it was fireworks. We didn’t know what it was.” When she realized what was happening,

A’zsia said, she climbed over the gate and ran.

Chevelle was waiting for Angelica and was toward the back of the bar when the shooting began. Alex wasn’t far away.

“We didn’t know what it was,” Alex said. “Maybe fireworks, or maybe it was the music.The new Drake song was playing.”

Chevelle said that when the shots started, she crouched down. “Then we raised up a little to look around, and then I hit the floor, and I stayed there. I was the last one to get out” before police moved in and the gunman holed up inside a nearby bathroom where many of the club-goers were hiding, staying there for more than two hours before being killed by police.

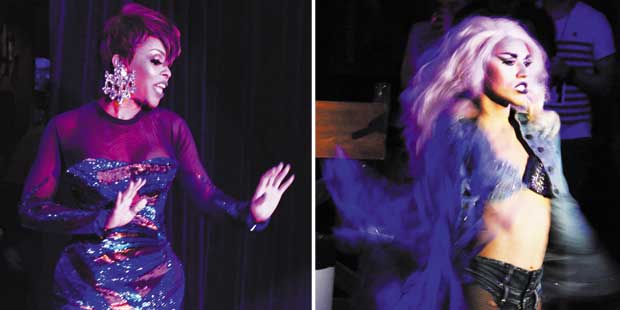

Angelica Sanchez, left and MrMs Adrien

“I was curled up in a ball on that floor. There was a group of people on this side of me, and another group on that side of me. We all hit the floor. When I looked up that second time, they were all gone. Just gone. I jumped up and I ran” out on to the patio and out the back gate, Chevelle said.

Chevelle said that the gunman, at one point, was in a different room of the bar, with the building’s cinderblock wall between them. “But it still sounded like it was right there, right on top of you. So close. You could hear bullets hitting the concrete — ting! Ting! Ting!”

Alex had run the other way, heading for the one place he thought he would be safe: the dressing room, which had a lock that required you to punch in a numerical code before it would open. Angelica was there, along with several club patrons. They, too, could hear the gunman continuing to fire.

“You could feel the sound,” Alex said. “You could feel the sound of those shots vibrating in your chest.”

Angelica nodded in agreement, saying that sound has stayed with her. “Afterwards, on July Fourth, I was at Parliament House [another Orlando bar], and it’s right next to where they set off all the fireworks. And when the fireworks started going off, it took me back, it physically took me back to that night. I had to grab hold of a tree to keep from falling.

“But the thing is, looking back now, I know, every bullet you heard that night, that was a life. Somebody’s life. That’s what I can’t take now,” she said.

For her part, Angelica said she wasn’t sure how she ended up in the dressing room. It wasn’t until this week, during a Wednesday afternoon interview, that A’zsia offered some clarification. “You were on the patio with me,” A’zsia said. “When it all started, you said, ‘What fool is setting off fireworks in this club? Who’s shooting in here? Let me go in here and find out what’s going on.’ You went in, and you didn’t come back. And I went over the gate.”

What she does remember, Angelica said, is that sense of denial. “It was surreal. I just kept thinking this can’t be happening. This isn’t real.”

Chevelle said that as she ran from the club, maybe five or six minutes after the shooting started, she could see the police moving in. ‘They were already there, and they told me to keep running, so I did,” she said.

She ran to a friend’s house nearby, sheltering inside as she began to text her roommate, Angelica, who was trapped inside. “I told her I didn’t know what was happening. I told her to be quiet,” Chevelle remembered. “I called 9-11, and they said to stay hidden. They told me to tell [Angelica and the others hiding in the dressing room] to be quiet, to turn off their phones and to be quiet. They [police] said to tell them to stay where they were.”

It was more than two hours later before those still in the club and still alive were rescued, because the gunman — hiding in the bathroom with his hostages and victims — was calling 9-11, telling police he had bombs, that there were snipers on rooftops around the club.

“They couldn’t move in sooner because they didn’t know for sure what was happening. They couldn’t be sure that coming in sooner wouldn’t end up with everybody dead,” A’zsia said.

She, like the others, is quick to brush off any criticism of the Orlando Police Department, the Orange County Sheriff’s Office and the FBI and other federal investigators. “They did a great job that night,” A’zsia said, with others chiming in to note that all the agencies involved have been very careful to make sure that every officer involved in investigation is part of the community or has experience working with the community.

Alex noted that one OPD officer, Tim Stanley, that he met that night “called me the next day. He calls all the time just to check on me. It’s been very comforting.”

Angelica added, “We’ve been so grateful to the first responders that were there and have been involved. There were officers and EMTs who came in even though it wasn’t safe.

And they check in with us all the time, checking to make sure we are making it OK.”

Everyone who lived through that night, the staff members agreed, carry the effects of it with them. But the love and support of their city and the LGBT community nationwide is pulling them through. Angelica said that as they travel to different clubs, people want to talk to them, touch them, hug them. It’s as if, she said, the presence of the Pulse staff members is helping others heal, and Alex added, the love they feel flowing over them is helping the staff members heal, too.

It’s different now, they all agreed. They are different. A’zsia said she finds herself more impatient these days with the idea of being still, “having to stand in line somewhere, having to be still.” And being in crowded clubs where they are surrounded, unable to move freely, can be unnerving. “It gets a little scary for us sometimes,” she said.

Angelica and Axel both described how they are always on alert these days, always looking for an exit. “It doesn’t matter where it is — a movie theater or a club or a grocery store, anywhere. You’re always looking around, always watching,” Axel said. Angelica added, “Every room I walk into, the first thing I do is look for all the exits, look for how I’m getting out of there if something happens, looking for the way to escape.”

She added, “It’s getting better. Every day it’s better. But still, it’s mind-boggling at times. It’s like, I’m sitting here in this room, talking to you, and I walk out for a minute and when I come back, you’re gone. Just gone. There are people who were there, and now they’re just gone.”

Still, the six agreed, they won’t let the fear stop them.

“You just can’t live your life in fear,” Chevelle added. “Every other day it seems like something else happens. But you can’t stay secluded, not and be who we are as gay people.”

“That’s our message now, everywhere we go — not to live in fear. Because if we do, that fear will trickle down. It will affect everyone, and that will hurt the gay community’s economy, it will hurt the whole economy, if we are too afraid to go out anywhere,” Angelica said.

She continued, “It’s hard for us sometimes now to go out, to be in a bar. But this is our livelihood. It happened in a bar. It’s happened in a church, in a movie theater, in a school.

Are people not going to go to church any more, not go to the movies or send their kids to school? We can’t let it stop us. If we live in fear, then we live in shells, alone.

“We’re not going to let that happen

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition August 5, 2016.