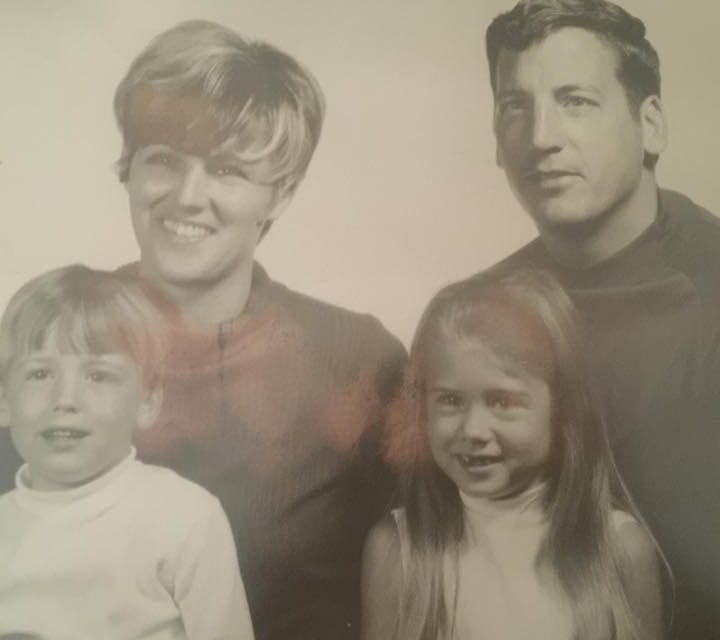

My family, about 1970.

One of the first things they teach you in News Writing 101 is “how to write an obituary.” It’s seen, I think, as a low-man-on-the-totem-pole kind of assignment, one not requiring special skills. It is, admittedly, formulaic — more so than most other kinds of stories: Name of the deceased, age, family, some significant personal achievements; if it’s a famous person, there’s all that much more to write about.

This past year, I’ve written more than my share of obits of people I was close to, or fond of: Bruce Wood, Nye Cooper, Terry Dobson, Jac Alder. Some were hard, or emotional to do. What no one really teaches you is how to write an obit for your own mother. Which is what I had to do last week.

My mom, Patty Jones, died after an illness that lasted about two months — not completely sudden, but certainly not unexpected, either. She was only 72, which seems young to me, and despite some bouts with bad health in the past, she seemed fine until this summer. It happened 1,000 miles away, so I had to sit out here in Dallas alone while my dad and sister were dealing with it at ground zero. As the writer in the family, I was tasked with responsibility for the obit on behalf of the whole family. I did it, and it was fine. Several people who read it told me how good it was. But they were wrong — so, so wrong. And I don’t think they knew it.

Because writing 300 words that encapsulate the life and legacy of your mom is something no one should be expected to do. Birth, marriage, kids, grandkids. She was a tireless volunteer. She was a great cook.

But she was also my mom. And I couldn’t really say what I wanted to, because it wasn’t about me — it was about her, as well as the rest of the family, mostly my dad, who was devoted to her for 54 years. How do you tell strangers that one of the best things about your mom is how much your dad loved her? My dad was the most loyal and affectionate husband I have ever had the privilege to know. Mom’s friends were jealous that she had such a great husband. But it was not just him, but how she made him want to be so good to her. The greatest gift a father can give, it’s said, is to show his children how to love, and by that measure, my dad is a role model without measure. I lost my mom; he lost the love of his life. How do you put that in 300 words and feel anything but inadequate? Their love wasn’t a series of cold dates on a calendar, but a lifetime together.

How do you put in a death notice that you mom wasn’t perfect? We fought when I was a teenager. I’m not ashamed of it, though not proud, either; but the relationship between a mother and child (not just me, but my sister, too) is a collection of highs and lows, missteps and synchronicity. Children are a part of their parents, quite literally. But they are also their own beings. I will never know how difficult it is to be a mother, though I respect and admire how singular my mom was at doing her best. Her love for her children was unconditional, and you felt it at every point along the way.

I remember lots of stupid things about my mom, too — things no one would care about. Like how she did not have a terrific sense of humor, but she respected my (and my dad’s) near-constant clowning. I don’t think she understood us, but she tolerated her boys and their silliness. I remember the first time I felt my mom treated me as a real adult, just when I needed it. But I also recall fondly those times she treated me as her baby. I wish she were here now to do that, because I’ve never needed it more.

She took care of the entire family. She was an only child who married the youngest of seven siblings. She knew everyone’s birthday and kept in touch with them. She organized our lives in ways we can only begin to imagine. Mom was the one person everyone in the family would turn to for solace and advice and an ear when something terrible happened. Losing her is losing your confidante, your guidepost, your rock. It’s a cruel irony — the universe daring us to get along without the one thing that has been there for all of us, for half a century. It’s unfathomable.

For at least 25 years – since I moved to Texas — I spoke on the phone with my mom probably twice or three times a week. Hearing her voice meant everything in the world to me. I always told her I loved her, and she did the same. I think more than anything, not being able to chat with her about life’s daily nonsense (recipes, movies, work) is what hurts the most. She was my mom, but she was my friend, too. We didn’t see eye-to-eye on politics, so we steered clear of that topic as much as we could. But she was smart and thoughtful and as opinionated as any woman I’ve ever known. All my life, people have said to me, “you remind me of your mother.” It takes a while to realize what a compliment that is.

My mom was an inveterate deliverer of care packages. She’d make fudge, or cookies, and send me knickknacks she thought I’d enjoy. She babied her “granddogs.” She was down-to-earth but had high standards, too. I learned more lessons — by far — from my mom than I did from every teacher, job and friend I’ve ever known combined. That’s because you listen to your mom in a way you don’t anyone else.

Take, for instance, this earlier memory: I was a kid, and someone had died. People kept saying to the bereaved, “he’s in a better place.” I asked my mom what that meant. “It means he’s in heaven and isn’t in pain anymore,” she explained. “Well, if it’s a better place, why are people crying?” I asked. “Shouldn’t they be happy for him?” “You’re right,” she said. “They won’t be able to be with that person anymore and it makes them sad. I guess people cry because they are selfish at that loss.”

I’ve thought a lot about that these past days as I choke back tears hourly. I am selfish at not having her around from now on. I won’t be able to talk to my mom anymore. That makes me sad. But she still will teach me lessons. Probably no one had a greater influence on my life than my mom. Missing her is hard, but much worse would be never having known her at all.