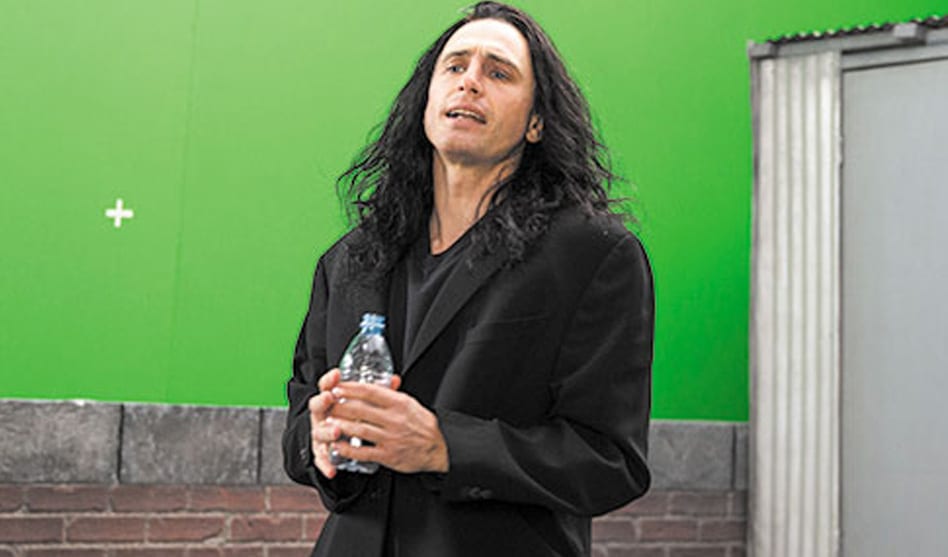

The Disaster Artist. It’s easy to make a bad movie about a good one, but vice versa? Director James Franco threads that needle with The Disaster Artist, his loving dissection of the reputed worst film of all time, a lurid romantic drama called The Room, created by the passionate but talentless weirdo Tommy Wiseau (also played by James Franco). If you haven’t seen The Room, trust me: It’s easily as bad as you have heard, a kind of perfect storm of incompetence; it’s instant camp. But Franco also turns this oddly specific chronicle of hubris into a universal story about the soul of an artist. After all, nobody said you had to be good to be an artist. Franco’s performance — perfectly matching Wiseau’s own inexplicable Middle European accent, his stilted affect, his otherworldly unusualness — is the best of his career.

The Shape of Water. A mute but educated cleaning lady (Sally Hawkins) is one of the faceless nobodies in 1960s America, along with her black co-worker (Octavia Spencer), her gay neighbor (Richard Jenkins) and, as it so happens, an otherworldly amphibian man-monster (Doug Jones), trawled out of a swamp and subject to vivisection by the U.S. government in a program spearheaded by a creepy right-wing martinet with a sadistic streak (Michael Shannon). Director Guillermo del Toro’s political-fantasy-melodrama-horror-parable-period-piece toggles between the winsome, gorgeous reverie of a ’50s musical and low-budget B-picture sci-fi; it’s as if Woody Allen had remade E.T. with a script by Eli Roth. If those sound like impossibly incongruous parts with no chance of coming together effectively as a whole, well, somehow it works (mostly). Hawkins’ performance is a delicate study in expressiveness without words. In an age of Weinstein-esque predatory behavior, showing the abusive white male who subjugates and disregards an entire underground world of the dispossessed — disabled, black, gay, outré — has particular resonance.

Wonder Wheel. Woody Allen’s 40-plus films generally fall into the slots of screwball comedies (mostly the early stuff), wistful romantic comedies and proto-tragedies. Wonder Wheel falls firmly into the last category, but instead of the grim (though effective), Bergman-esque coldness Allen often evokes that way (Interiors, Match Point), this one is warm and singular; it’s clearly Woody, yet in some ways unlike anything he’s done before. He conjures the nostalgic appeal of 1950s New York (a signature) with a romantic appeal that sours, but the tone is unlike anything he’s done in memory. Kate Winslet, as a slattern housewife with a destructive son, makes for a terrific Allen heroine, but the revelation here is an amazing performance by Jim Belushi (seriously!) as Winslet’s befuddled but ingratiating cuckold. His earnest mumbling never devolves into sitcom-y winking. He’s just one of the surprises in this inventive slice of Americana.

Darkest Hour. If you watched Dunkirk this summer, you saw the boots-on-the-ground side of a knotty wartime debacle as politicians in Britain struggled to find ways to rescue 300,000 soldiers. Darkest Hour basically tells that story — and a little bit more — from the perspective of Winston Churchill, the newly-installed but widely disliked prime minister who barked his way through the (wait for it!) darkest hour of his nation, an existential threat that’s resolution could allow fascism to spread or be stalled for all time. (Well, until Trump.) The film is a showcase for Gary Oldman, still recognizable under jowly makeup, his voice more Jim Broadbent than Churchill. It’s a ferocious performance, full of bluster and self-doubt, the kind Oscar nominations were made for. Yet director Joe Wright never turns up the emotional screws; it’s no Lincoln. There are too many murky interiors, bland white male Brits and modest ambitions (it takes place over only a month) to grab you and suck you in. It’s perfectly respectable, well-intentioned historical drama, but that’s as far as it goes.

— Arnold Wayne Jones