The LGBT community is used to celebrating a victory by jumping into the next crisis. But this year we should take some time to celebrate

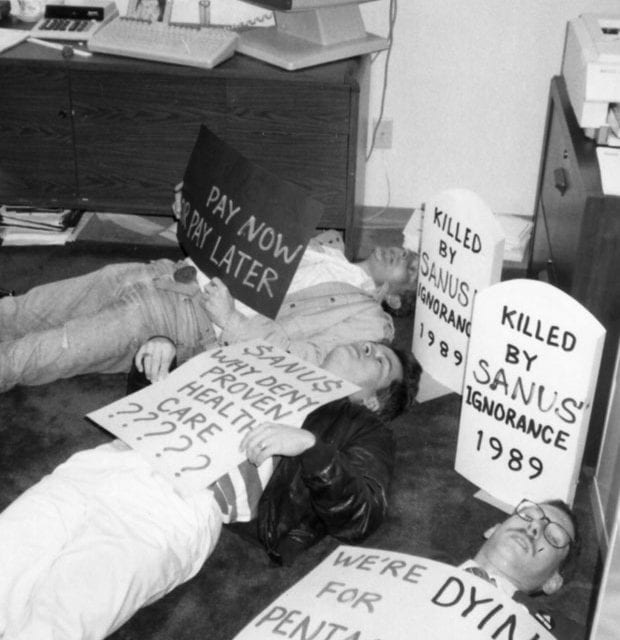

A group of protesters, above, in 1989 stage a die-in at the Sanus Insurance office in Irving after the insurance company refused to pay for treatment for people with AIDS. Activists participating in a LGBT rights march in Austin honor hate crime victim Nicolas West, who was murdered near Tyler because he was gay, below, top. Mary Franklin, bottom, accepts a donation to Resource Center’s food pantry, which she operated through the height of the AIDS crisis. In an interview on NPR, Franklin said she never had time to grieve because she’d run from a funeral to a hospital bed.

DAVID TAFFET | Senior Staff Writer

When the film The Dallas Buyers Club was released, National Public Radio interviewed Dallasite Mary Franklin, who ran the Resource Center Food Pantry during the height of the AIDS crisis but who began her AIDS activism working at the real-life Dallas Buyers Club.

The recorded interview took about 30 minutes, but less than a minute made it on the air. One of the questions that made it into the NPR piece was about how she dealt with all these people around her dying? Franklin said she never had time to grieve: She went from one friend’s funeral to another friend’s hospital bed.

With the advent of HIV medications in the late 1990s, people with AIDS began to return to a normal life. New drugs have since been released that are more effective and less toxic. But when those first medications were released, the LGBT community could begin to breathe.

The fight for equal right has taken a similar path.

While we were still busy dealing with the AIDS crisis in the early ’90s, additional, unconstitutional assaults on our freedom were thrown at us — Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell targeting gays and lesbians in the military, the Defense of Marriage Act and a slew of discriminatory state marriage amendments.

Finally, in 1996, the LGBT community scored a victory. That year, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Romer v. Evans that a Colorado constitutional amendment preventing cities from protecting its citizens based on sexual orientation violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Constitution.

Finally, in 1996, the LGBT community scored a victory. That year, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Romer v. Evans that a Colorado constitutional amendment preventing cities from protecting its citizens based on sexual orientation violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Constitution.

Although that was the first ruling that protected gay and lesbian rights, it seemed like a minor victory at the time. It meant a city ordinance in Denver would remain enforceable in that city, even if the people in Colorado Springs didn’t like it.

Dallas had no such protections at the time. Neither did any other city in Texas. What we had was the Homosexual Conduct Law, better known as Section 21.06 of the Texas Penal Constitution, which prohibited private, consensual sexual contact between adults of the same gender.

So here in Texas, we applauded Romer, then ran to put out the next fire.

The next victory came five years later, in 2001, when the James Byrd Jr. Hate Crime Law, named after a black man murdered in a brutal hate crime in Southeast Texas in 1998, finally passed the Texas Legislature, where the battle to enact substantial hate crimes legislation had raged since the early 1990s.

After Paul Broussard was beaten to death in an anti-gay hate crime in Houston’s Montrose neighborhood over July 4th weekend in 1991, Texas lawmakers passed legislation allowing for the collection of data on hate crimes, including those targeting gays and lesbians. The movement for a more comprehensive hate crimes law including enhanced penalties gained momentum again following the anti-gay murder of Nicholas West in November 1993 in Tyler. But it wasn’t until the murders of James Byrd Jr. in Jasper, Texas in June 1998, followed closely by the murder of gay man Mathew Shepard in Wyoming in October that efforts to pass a hate crimes bill really took off.

And it wasn’t until Byrd’s family stood up and insisted that the law bearing his name include protections for gays and lesbians that an acceptable bill was passed.

Well, they continued to kill us. But in a few instances, the penalty for doing so could be enhanced if they killed us because they hated LGBT people. And some police departments worked to investigate some crimes as bias-motivated.

Eight years later, in 2009, Congress passed — and President Barack Obama signed — the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act, named after the Texas man killed by white supremacists and the young gay man killed in Wyoming by two young homophobes. This took hate crimes laws to the federal level at long last.

In 2003, the LGBT community scored a really big win. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled, in Lawrence v. Texas, that sodomy laws like Texas’ violated the U.S. Constitution.

The Texas sodomy law was gone. For the first time we weren’t automatically criminals because of who we were.

But again, there was DOMA, which prohibited the federal government from legally recognizing marriage between two people of the same sex, and allowed individual states to ignore laws from other jurisdictions were marriage equality was recognized. And state constitutional amendments were passing around the country to outlaw any recognition of our relationships.

So we took a quick moment to celebrate Lawrence and the death of sodomy laws, then we rushed to try to put out the next fire.

Human Rights Campaign began counting the many special rights afforded to straight couples — more than 1,100 by the time the counting was done. Studies showed same-sex couples spent tens of thousands, sometimes hundreds of thousands of dollars more because of those special rights given to straight couples.

Then came Edie Windsor, a widow who had married her wife in Canada in 2008. Had she been married to a man, she would have paid absolutely nothing in inheritance tax. Since she was married to a woman, she owed more than $365,000 in taxes when her wife died.

Edie Windsor sued, challenging DOMA in federal court. And in 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the one section of DOMA prohibiting the federal government from recognizing marriages between people of the same gender.

The Windsor case was a huge win, yes. But didn’t get rid of all of DOMA. Texas and other states with marriage amendments could continue to discriminate just as they always had. And that partial victory over DOMA created a legal mess.

So we celebrated and went back into the streets and into the courtroom.

From left: 1. James L. Byrd was murdered in a brutal hate crime in Southeast Texas. His death spurred passage of Texas’ hate crimes law, named after him and including LGBT people. 2. Marriage equality plaintiff Jim Obergefell compares notes with HRC president Chad Griffin at a press conference in Dallas three days after the U.S. Supreme Court handed down a ruling in favor of marriage equality in June this year. 3. Tyrone Garner and John Lawrence walk with their attorney, Mitchell Katine, after a court hearing in Houston. Their case challenging Texas’ sodomy law went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court and resulted in a ruling that invalidated sodomy laws around the country.

How was the government going to deal with this?

One married Dallas couple had moved to Texas from California. A year later, they were about to return to their native state for new jobs, but one husband remained behind to sell the house and take care of other business. So for that period they were apart, the husband in California was legally married to his husband in Dallas but the husband in Dallas wasn’t married to his spouse in California.

But things began moving quickly after Windsor.

The IRS ruled it would recognize any legal marriage, no matter where the couple lived. One federal agency after another began to follow suit.

Couples around the country began filing lawsuits challenging their state marriage bans. Court after court struck down the bans.

Out of more than 60 marriage rulings, the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals, a U.S. District Court in Puerto Rico and one in Louisiana were the only courts to find the marriage bans legal.

Then in June, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down the Obergefell v. Hodges decision.

Jim Obergefell and John Arthur, his partner of 20 years who was dying of ALS, flew on a medical flight from their home in Ohio to a runway in Maryland. They were married on the plane and then returned home.

Arthur died two months later. Obergefell sued to have Ohio recognize their marriage for the sake of the death certificate.

The Sixth Circuit overturned a lower court ruling that would have forced the state to recognize the marriage in this once instance for the sake of one document. But it didn’t end there.

In June this year, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the Sixth Circuit and threw out all state marriage equality bans.

So now, where do we stand? DOMA is gone. Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell is gone. Sodomy laws are gone.

4. Judge Dennise Garcia marries Al and Greg, a Dallas couple together 30 years, three days after the Obergefell decision. The couple’s best friends served as witnesses. 5. Thea Speier and Edie Windsor were married in Canada. After Speier’s death, Windsor had to pay inheritance taxes because she was married to a woman. She filed a lawsuit that resulted in the Supreme Court finding part of the Defense of Marriage Act unconstitutional.

Make no mistake: There’s still plenty of work to do. Nationwide employment, housing and accommodation protections for the LGBT community are still missing, although some state and local laws exist in various places — including Dallas and Fort Worth — to prevent that sort of discrimination. Plano has some protections, and hopefully Houston voters will step up in November and approve the Houston Equal Rights Ordinance banning discrimination there.

On another front, tons of work still needs to be done to get protections and equal rights for the transgender community. Even many of the laws already in place to protect lesbians and gays specifically leave out protections for transgender men and women.

Even with legal protections in place, the hatred and the discrimination still exist. Just look to Rowan County, Ky., where County Clerk Kim Davis has become a hero of the right wing for refusing to abide by her oath of office and issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples.

For our community to truly be equal, for us to be sure that equality is truly safe, we must continue to work to change the hearts and minds of those that hate us. At the very least, we must work to make sure our protections and our equality outlive the haters.

Even still, we have a lot to celebrate this year. Even as we fight own, we cannot forget to celebrate — truly celebrate — how far we’ve come.

That seems to already be happening at Pride celebrations around Texas this year.

Houston Pride was held the day after the Obergefell decision. Crowd estimates ran as high as 500,000 to 750,000 people lining the streets downtown in the Bayou City to celebrate.

On Aug. 29, Austin Pride drew a record crowd of 150,000 people.

Will Dallas turn out in record numbers to celebrate Pride on Sept. 20?

The parade route is a few blocks longer than in the past so more people can get a front row seat. On Turtle Creek Boulevard, the parade makes a right and heads to Reverchon Park — instead of left to Lee Park as in years past — for a larger festival than in the past.

So let’s stop this year as we get ready for the 32nd annual Alan Ross Texas Freedom Parade and revel in how far we’ve come. Let’s take a moment to celebrate — truly celebrate before the fight continues.

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition September 18, 2015.