The sexy orgy to Saint-Saens’ familiar ‘Bacchanale’ is one of the few lively scenes in ‘Samson & Dalila.’ (Photo courtesy Karen Almond/Dallas Opera)

The staid Romanticism of ‘Samson & Dalila’ makes for a stagy production of dis-tressing biblical proportions

ARNOLD WAYNE JONES | Executive Editor

jones@dallasvoice.com

When asked why he made so many biblical epics, filmmaker Cecil B DeMille joked, “Why let thousands of years of publicity go to waste?” That approach wasn’t always the case, though. When Camille Saint-Saens wrote Samson & Dalila in the late 19th century, it was perceived as bordering on blasphemous — how dare he presume to put the Bible onstage! Yet to our modern ears, it seems pretty tame, and even misses many of the key points of the familiar story of a long-haired strongman and a Philistine woman who seduces him and, in an act of history barbery, shaves his mane and robs him of his strength. But many of Samson’s famed exploits as a meta-human are barely acknowledged — he doesn’t slay anyone with the jawbone of an ass, and the chopping off of his empowering tresses is performed offstage — a bit of counterintuitive dramaturgy that defies the imagination. Saint-Saens could have learned a thing or two from DeMille.

When asked why he made so many biblical epics, filmmaker Cecil B DeMille joked, “Why let thousands of years of publicity go to waste?” That approach wasn’t always the case, though. When Camille Saint-Saens wrote Samson & Dalila in the late 19th century, it was perceived as bordering on blasphemous — how dare he presume to put the Bible onstage! Yet to our modern ears, it seems pretty tame, and even misses many of the key points of the familiar story of a long-haired strongman and a Philistine woman who seduces him and, in an act of history barbery, shaves his mane and robs him of his strength. But many of Samson’s famed exploits as a meta-human are barely acknowledged — he doesn’t slay anyone with the jawbone of an ass, and the chopping off of his empowering tresses is performed offstage — a bit of counterintuitive dramaturgy that defies the imagination. Saint-Saens could have learned a thing or two from DeMille.

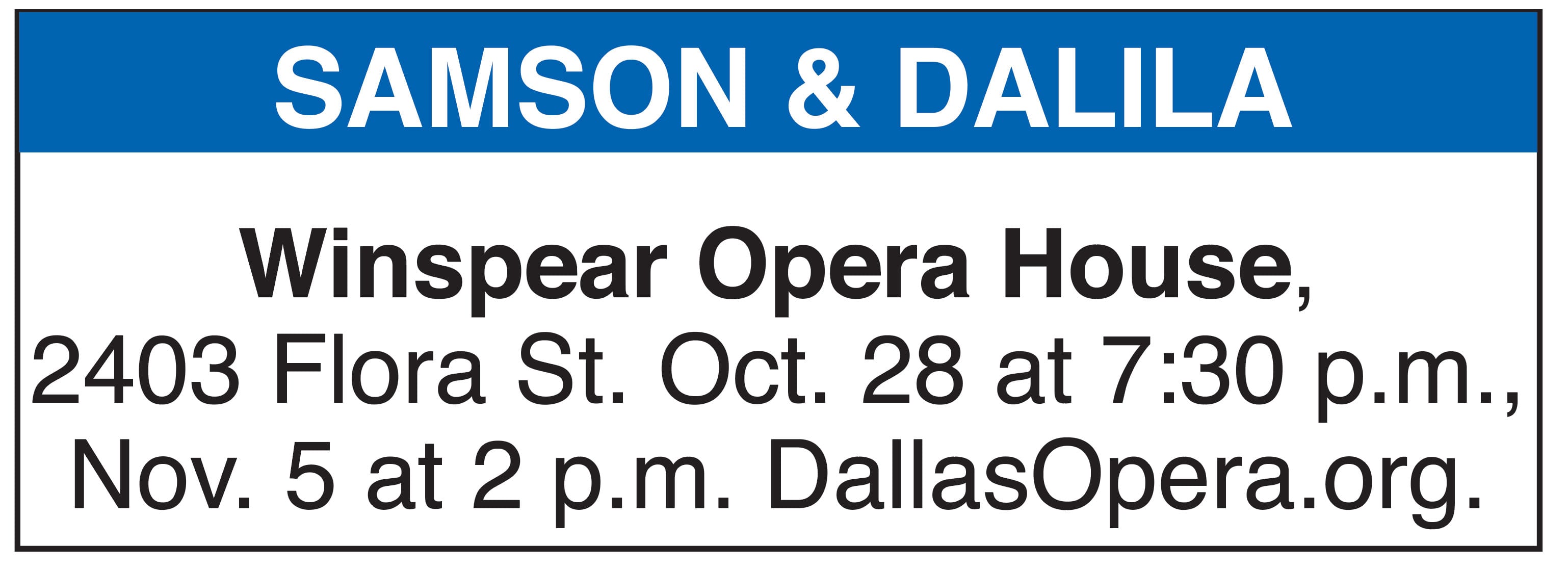

Instead, the opera, at the Winspear in repertory with La Traviata, is fat with soaring strings and gooey, overwrought passages. Saint-Saens was a romantic composer — Samson & Dalila is his only opera still regularly performed — and it spends more time with swooping arias about prayer and religious devotion then it does on actual character development or (gasp!) action. Although two of the areas are standards in the mezzo concert repertoire, and the third act “Bacchanale” features an exotic oboe and orchestral phrase that will sound familiar to anyone who’s ever seen a movie featuring a cobra or men wearing turbans, the score of Samson & Dalila is one of the less exciting musical works in the canon. There are many sweeping strings and florid passages, but no real dramatic impetus. (The libretto is no better, with overripe lines such as The arrow of death is less swift than your lover flying into your arms. Ugh.)

The production struggles to overcome its origins as an oratorio. Act 1, which contains some lovely choral work, is slow and stagy, as Samson (tenor Clifton Forbis) encourages his Hebrew brethren to revolt against their Philistine captors. Samson, though, is portrayed not as divinely super-strong, but more as a charismatic leader, which makes his eventual destruction of the temple seem to come from nowhere. Act 2 is a showcase for the vocal prowess of Dalila, performed here by mezzo-soprano Olga Borodina, but again, it is thin on dramatic momentum. While her notes are rounded and rich, there is a somewhat nasally quality to her voice, and she does not convey the sensual appeal of Dalila. (By contrast Michael Chioldi, in the role of the vicious Abimelech, gives a spirited and naturalistic performance, but is dead by the middle of Act 1.) Only the outrageous and sexy third act orgy, complete with modern dancers and half-naked men covered in gold, perks up the rather mild pacing by stage director Bruno Berger-Gorski. It’s not enough to rehabilitate it from its slugging beginnings.

Verdi’s La Traviata opens Oct. 27. Look for a review online at DallasVoice.com.