Long before Mica England took on DPD’s anti-gay hiring policies and won, Slade Childers was fighting for his right to work for the Dallas police

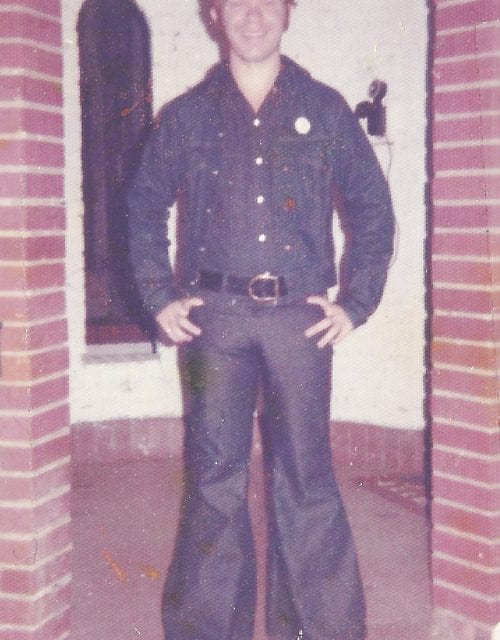

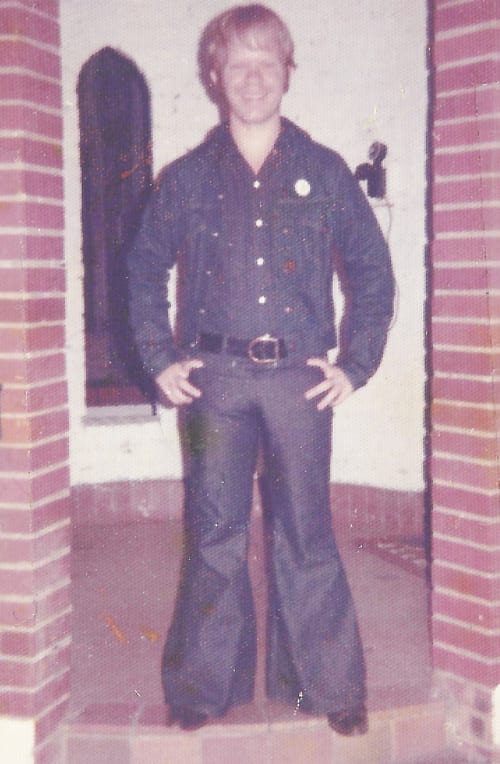

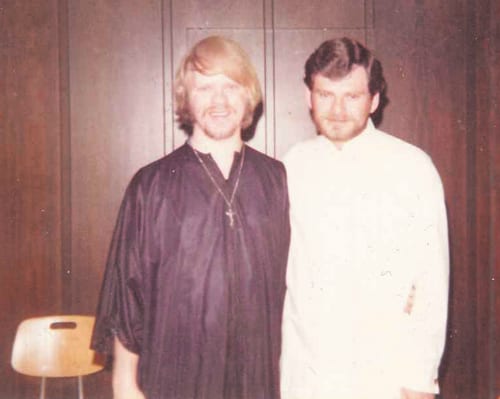

Slade Childers, left, with his “other half” Don Armstrong. Below, the Dallas Water Department in 1972. Childers is in red in the front row. (Courtesy Slade Childers)

DAVID TAFFET | Senior Staff Writer

When Mica England sued the Dallas Police Department in 1993 for rejecting her employment application because she was openly lesbian, her victory changed the relationship between Dallas and the LGBT community.

But things were very different in 1975 when Steven “Slade” Childers was rejected by the department because he was gay: He sued and lost.

How it began

Childers’ battle began when, while working for the Dallas Water Department, he requested a transfer to DPD. In a letter rejecting the transfer, Dallas Police Chief D.A. Byrd explained to that Childers’ request was being rejected based on Section 21.06 of the Texas Penal Code, the state’s so-called “sodomy law” that criminalized private, consensual sexual conduct between adults of the same gender. (That law remains on the books in Texas to this day, even though it was found unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court in Lawrence v. Texas in 2003, more than 13 years ago.)

Childers’ battle began when, while working for the Dallas Water Department, he requested a transfer to DPD. In a letter rejecting the transfer, Dallas Police Chief D.A. Byrd explained to that Childers’ request was being rejected based on Section 21.06 of the Texas Penal Code, the state’s so-called “sodomy law” that criminalized private, consensual sexual conduct between adults of the same gender. (That law remains on the books in Texas to this day, even though it was found unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court in Lawrence v. Texas in 2003, more than 13 years ago.)

Slade Childers today

Even though it’s still on the books, 21.06 can’t be enforced today. But back in 1975, the city’s police department was making personnel decisions based on the sodomy law.

After his request was rejected, Childers filed a grievance with the city, basing his complaint on the fact that the rejection violated his religious freedom, and that he was being discriminated against because of his sexual orientation. The director of the water utilities department requested an explanation from Byrd.

Byrd claimed the rejection had nothing to do with Childers’ religion when in fact, it actually had everything to do with his beliefs. Childers belonged to Metropolitan Community Church Dallas, now known as Cathedral of Hope, which affirmed LGBT people. Byrd said he was rejected entirely because he was gay.

“A person commits an offense if he engages in deviate sexual intercourse with another individual of the same sex,” Byrd wrote. Citing Paragraph G of the employment code, he added, “No employee shall cohabit with any type of sex pervert of the same sex.”

And Paragraph X allowed him to reject employment “for violation of any federal or state statutes.”

Childers was applying for a job in the property division. Byrd found that problematic because, he claimed, it was a “sensitive position.”

“Moreover, this position could conceivably make him privy to information concerning perspective [sic] enforcement activities pertaining to sexual offenders and to place him in a further potentially compromising position with his closest friends and associates.”

Childers said that when he asked what evidence he might see that might put him in a compromising position, he was shown dildos, which were illegal in Texas then.

At the time, Childers recalls now, DPD regularly raided gay bars. In addition, they would send undercover officers into the bars to distribute invitations to private parties set up in private residences. Once the party was underway, police would back a paddy wagon up to the house and arrest anyone who didn’t escape through the windows.

So the chief was worried Childers might tip friends off to planned entrapment operations.

Childers filed an appeal, writing: “My complaint is on the grounds of religious discrimination in regard to my sexual orientation.”

Childers, 24 at the time, had been working for the city since 1969. He had marched in Dallas’ first Gay Pride Parade in Dallas in 1972, with the MCC contingent, and, he said, someone he worked with saw him marching with the MCC group in the parade and outed him at work.

That’s when “jokes, offensive language and the usual put-downs” began, he said. When he eventually filed a grievance over his transfer request being denied, he included a newspaper clipping from 1973 that explained that homosexuality in Texas was downgraded from a felony to a misdemeanor in the rewritten Texas Penal Code.

When Childers took a civil service test, while he was preparing to ask to be transferred, he received the highest score given. At his interview with the police department, he was asked about his religion, a question that would now be illegal under Title VII.

When he was asked about MCC, Childers explained the church’s outreach to the LGBT community. Childers said the interviewer assured him that he had no problem with that, but he wanted Childers to know there were “cops that like to bust fags.” Childers assured the interviewer that his private, religious life and his work life were separate, and the interviewer told him he’d find out in three days.

After that interview, Childers was so confident he had gotten the job that he got his hair cut and his sideburns trimmed. (It was the 1970s and everyone — except Dallas Police, it seemed — had long sideburns).

But when Childers called back, the interviewer told him he was still interviewing candidates. He said he’d call Childers to let him know what decision was made. He never called.

A year later, Childers took the civil service exam again, scored even higher, and re-applied for the job when it opened. At the interview, he asked why he wasn’t hired the previous year.

“Because of your gay activist activities at Metropolitan Community Church,” the interviewer told him.

In Childers’ eyes, that constituted religious discrimination and formed the basis of a lawsuit he filed when his grievance appeal was denied.

The lawsuit

In a deposition for the lawsuit against the city, Joseph Werner, an assistant city attorney, questioned Childers.

“I don’t mean to embarrass you by my questions,” Werner told Childers during questioning. “The subject matter of the lawsuit necessarily involves some things which may be embarrassing, but my questions are required by the allegations that you’ve made in your lawsuit and by your own description of yourself, and I don’t mean to attach any stigma to that . … ”

But it turned out that Werner was the only one embarrassed by the deposition questions. Childers described himself as a deacon with MCC and said he was proud of his religious beliefs, and that included being proud of himself.

Werner asked him about being homosexual. Childers kept answering that he was gay. Werner repeatedly asked questions about what the word meant. Childers explained that being gay was more than having sex.

Finally, Werner asked, “Do you prefer that I use the word gay in referring to you?”

At one point, Werner asked Childers if he considered himself to be a sex pervert. Childers said not only did he not consider himself a sex pervert, but neither did the American Psychological Association, which had recently changed the classification at a national meeting held in Dallas.

When asked about MCC, Werner asked if the church tolerates people whether they’re gay or not.

“Well, let me rephrase that,” Childers said. “It’s a church which welcomes people whether they are gay or not.”

Werner asked again using the word “tolerates.” Childers objected and Werner appeared to become a little flabbergasted and asked what’s wrong with that?

“How can you say a church tolerates its members?” Childers asked.

In another interesting exchange, Childers refers to his partner as his “other half,” and Werner obviously had trouble understanding the term.

Childers explained that his “other half” was like Werner’s wife was to him, except they weren’t married, adding that he just didn’t have a better term.

Between the time Childers filed his grievance and the time the case came to court, Childers had left the water department and broken up with his partner, Don Armstrong.

He moved out of Dallas and took several temporary jobs until meeting Ralph Josephs in California. He moved in with Josephs and settled there, and the two remain a couple today.

The outcome

The case never went to trial. Instead, Childers said he and his attorney, Fred Time, met privately with the judge and city representatives.

The city offered Childers a $9,000 settlement and, he said, he considered it seriously because, at the time, he and Josephs could really have used the money, since he was not working.

“But,” he added, “I couldn’t take it and live with myself.”

So he left it to the court to decide, and the judge ruled against him. But, Time later told him, it was the longest decision the judge had ever written. He said the judge clearly saw discrimination, but couldn’t find a law to back up Childers’ claim.

They appealed to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, which refused to hear the case.

During the lawsuit, Childers said MCC Dallas never embraced his fight for equality against the city. In fact, the board of directors voted against supporting his case. However, the Fellowship of Metropolitan Community Churches, which is based in California where he was living, voted full support for his case.

Childers said that after the case closed, he visited Time’s office in Dallas and was worried about the huge legal bill he faced. Time told him the legal fees had been covered. To this day, Childers doesn’t know whether Time simply wrote off the fees or if someone stepped in to fund the case.

In January 2016, Childers and Josephs celebrated their 40th anniversary. They still live in California where Childers works for the federal government.

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition October 21, 2016.