Facebook’s ‘community standards’ rules are so vague, some in the LGBT community fear anti-gay mischief could chill free speech on social media

DEL SHORES | The Texas-born writer and director did not get any satisfactory answers for why his Facebook page was blocked … until national media got involved. (Photo courtesy Paul Boulon)

ARNOLD WAYNE JONES | Executive Editor

Del Shores has made a living pissing people off, and he’s not about to stop now. But these days, it can be more of a challenge than it used to be.

Although best known for writing Sordid Lives, Southern Baptist Sissies and episodes of Queer as Folk, it’s another form of expression that has gotten him into trouble recently: As an enthusiastic poster on Facebook.

The Texas-born Shores has an ornery streak when it comes to issues related to matters close to his heart, especially the intersection of homosexuality and religion, and he’s not shy about expressing his opinions. But several weeks ago, such frankness resulted in something severe: A suspension of privileges from his Facebook account.

That might not sound like such a big deal — who can’t use a break from social media, if just for a while — but it was precisely because Shores uses social media to communicate with his fans. It would be as if he suddenly lost Internet access or an email address.

“I’m now approaching 36,000 fans, and I have a very high-sharing page,” says Shores. One post, a meme that said, “Don’t use the bible to beat people down,” was shared more than 250,000 times, he says.

“A lot of my posts are shared, especially if the ones that are very pro-gay rights or pro-gay marriage. Then, when their friends comment on those posts, those posts go to the mother page,” he adds.

Twice in the past, complaints have led to temporary suspensions of his Facebook privileges, but those last only a few days. It was this last time — the third occasion — that put Shores in fear and awe of the power of Facebook.

So just how did it all happen?

“I’ve pissed a lot of people off over the years. Anybody can comment on my page and many people ‘like’ it merely to troll it. What I do is, I patrol them, and my fans [and I] fight back. In this particular instance, there was this guy who was being biblical and anti-gay. I asked him to delete [his comments]. I can only assume he got his prayer lawyers after me.”

In Shores’ scenario, the disgruntled reader mobilized enough of his friends to complain directly to Facebook about the content of Shores’ page. Shores disputes that there was any obviously objectionable content (no nudity or out-right hate speech); rather, his pro-gay posts were being attacked by a homophobe.

But the truth is, neither Shores nor anyone else who encounters a blocked Facebook page, will ever know for sure what happened.

And that’s the very problem.

“I think that Facebook does not do a thorough investigation,” Shores opines. “They get 20 comments on one post or one picture, and they react. I’ve had so many complaints [over the years] that now I get a 30-day suspension [rather than the less obtrusive three-day].”

It took a while to get satisfaction.

“I waited, I complained, and said this is unjust and unfair. But Facebook [did] nothing,” he says. “My story [about my suspension] was covered in the HuffPost and through a blog in Ontario, Canada, and that’s what got her attention,” Shores says of the Facebook rep who finally contacted him. “Facebook reversed the ban and said they wanted to apologize and I publicly accepted their apology.”

Dallas’ Will Kolb had a similar problem with one of his 38 Babylon groups, online communities based on Facebook.

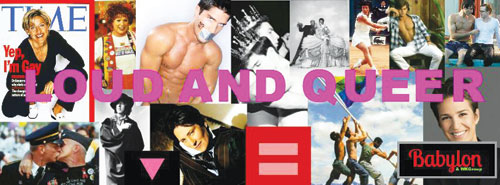

“There are 128,000 people in those groups, with 500 to 600 joining every day,” Kolb says. So it was a surprise that one of his smaller pages — called Loud and Queer, with just 1,000 followers — caused so much trouble.

“I woke up that morning and signed on and all my admins had been disabled,” he says. He was also met with a note from Facebook that said if, through the Babylon groups, he continued “this behavior,” they would discontinue his personal Facebook account.

“I asked if there was anything I could do,” he says, “they never responded. They shut it down, got barraged my media people and suddenly it came back up. But I never heard from anyone — no comment, no apology.”

DID ‘QUEER’ QUEER THE NET COPS? | Will Kolb’s Loud and Queer page on Facebook was suspended last month for reasons never made clear to him. He suspects that the word ‘queer’ in the title may have offended a disgruntled reader.

Kolb thinks he knows who was causing the mischief — thinks, because, as with Shores, he has no idea what criteria were imposed or who the complaining party was. But he’s still not clear what was said that got him tagged.

“Maybe they tagged the word ‘queer,’” he speculates. Kolb didn’t change the name, though, and — with help from Shores — the suspension was revoked. Kolb still doesn’t know why or how.

As with Shores, Kolb suspects he was closed down “for being a hate group or promoting hate speech, but that’s really strange, because its an LGBT support group — history, news, etc. We do point out some of the bashers, but are never hateful.”

Kolb and Shores agree that the major concerns are the lack of transparency and responsiveness, and the vagueness of the rules that can be broken without even knowing how.

“I don’t know if they are shorthanded or if they get 500,000 complaints a day, but I got no response, just as I have not the last two times I was banned. I was banned over silly things — always a post so-called Christians get mad at.” (For instance, replying to haters by saying, “God prefers kind atheists to hateful Christians.”)

“If they want to have rules, they need to state them up front — ‘don’t use these words.’ But you cannot just arbitrarily make it up. They’re shutting us down without recourse,” Kolb says. And he worries about the chilling effect — especially, but not exclusively, for LGBT members.

“They could throw off anyone but my concern is the tide could turn quickly on all the LGBT groups. There’s no LGBT liaison to ask why. What I would like to see is Facebook hire someone who has some contact with the LGBT community. This may be a sensitivity and training issue.”

“I pointed out that it’s interesting to me [Facebook was] still taking my money, because I advertise my events daily on Facebook, even as they disabled my page,” Shores says.

“If you’re going to monetize — and Facebook wasn’t originally like that — then you need somebody we can call, even if they are in India.”

Indeed, it is because Facebook is so prevalent in our lives — and yet is a corporation that makes up its own rules — that many of its members are so concerned.

“The world has changed,” Kolb says. “This is how people communicate, and there are serious consequences [to being blocked]. It puts us on pins and needles. And we need to be able to talk to some human being.”

“I’ve always feared losing my page, which can happen,” adds Shores.

“It annoys me they never said, ‘We’re sorry and here’s why we goofed,’” says Kolb, although Shores did get some more direct contact.

“I’m very grateful to Facebook,” he says. “I wrote [to them] very professionally — this is what happened, and what I don’t understand, and this is not something that should not have happened.”

Still, he says, there were “very, very vague when I asked specific questions about the suspension. But I was just glad to find out there were actual humans who work at Facebook.”

Nevertheless, there remains the need to have a mechanism in place for member complaints. The evidence?

Dallas Voice contacted Facebook’s corporate communications officer via email for information on why some posts or users are blocked and what process is determined to decide who and what to block. A spokesman — not the communications officer to whom the email was sent — responded with a brief phone call in which he referred the Voice to Facebook’s community standards, which are posted online.

The spokesman also promised to send an email with links and other information, but the Voice never received the email. By press deadline, Facebook representatives had not responded to a second email.

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition July 11, 2014.