For 10 years, supervisors got away with calling Almodovar ‘big girl’ and ‘fag’ without consequences despite Navy’s no tolerance policy for harassment

DAVID TAFFET | Senior Staff Writer

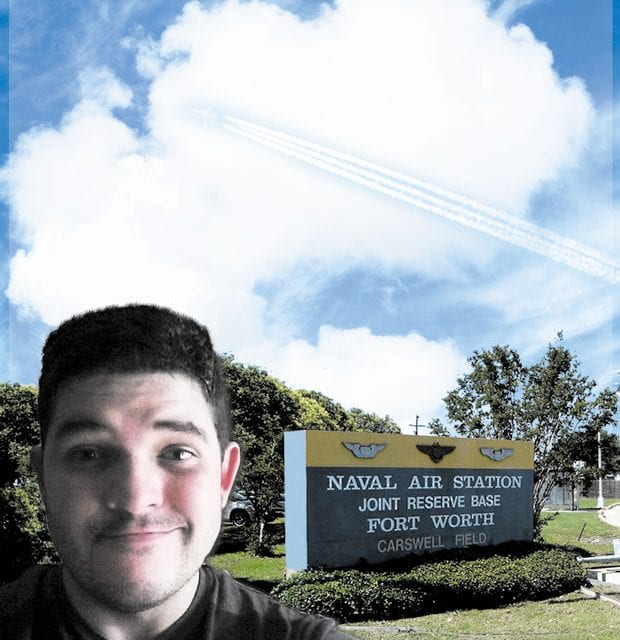

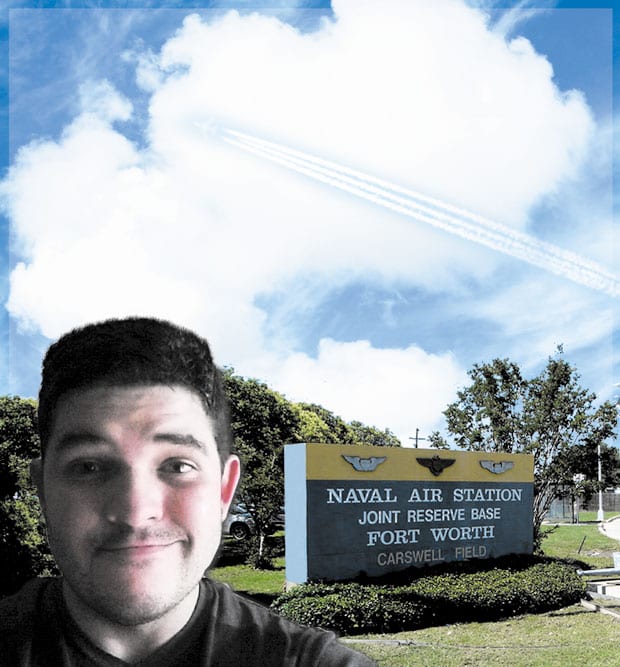

A North Texas man has filed suit against the U.S. Navy, charging that officials at Naval Air Station Fort Worth at Carswell Field allowed officers and other staff to target him with anti-gay harassment and bullying throughout his 10 years as a civilian employee there.

Allen Almodovar served as secretary to the fire chief at NAS Fort Worth — commonly known as Carswell — from 2006-2015. During that time, he saw the military scrap its Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell policy — which prevented open military service by LGBT people and also, supposedly, prevented witch hunts intended to find and discharge closeted LGBT people.

Almodovar never “told” during his time at NAS Fort Worth. But in fact, DADT never applied to civilian employees anyway.

“At work, I never said anything about being gay,” Almodovar said. “It was nobody’s business at work.”

But still, the harassment continued. His attorney, Chad Norcross, said bullying started soon after Almodovar began working there, following an internship at the base.

Almodovar said while he never denied he was gay, he never came out at work, either. He simply didn’t talk about his personal life at the fire station.

“I never did things that made them think I was gay,” he said. “I never gave them a reason to believe otherwise.”

The bullying began with derogatory remarks and fat jokes. Almodovar has asthma and when he used his nebulizer, he’d get comments like, “What are you sucking on today?”

Once at the fire station, he was giving an assignment to a firefighter and was correcting him about something related to his task. Rather than accept the correction, the firefighter said to him, “Don’t get mad at me because you can’t get married in Texas,” and then bragged about the comeback to two others.

A chief repeatedly referred to Almodovar as a “big girl.” Even though Almodovar told the chief that the name bothered him, the man continued using it. In one instance, as Almodovar was leaving the fire station with one chief, a second asked if they were going to the post office. The first chief replied,

“Yeah, I’ll take that big girl anywhere she wants to go.”

In another instance, while Almodovar was on the phone with a vendor, one person in the office asked loudly, “Who are you talking to?” to which a second person replied, “Probably his boyfriend.” Both comments were made loudly enough for the vendor on the other end of the telephone line to hear.

“I had to apologize to the vendor,” Almodovar said. “It was done to humiliate me.”

Such incidents, Almodovar said, were endless. In one case, someone gave Almodovar a photo of actor Erik Estrada pointing his finger, with the caption, “I just want you to know you’re a homo.” In another, Almodovar said, he was talking to one of the supervisors when someone in the office grabbed and twisted his nipple.

He reported that to the commanding officer, who dismissed it as “horseplay” based on what others in the office said.

“Had that happened to a woman,” Almodovar said, “any reasonable person would know it wasn’t OK.”

Almodovar said he is suing because of how long the harassment lasted, because of the intensity of the bullying and because it was coming from management. He said he began by going through the EEOC process.

“Dallas EEOC summarily dismissed it,” Norcross said. “Allen appealed the case to D.C., and we cited several Supreme Court cases of hostile work environment based on sexual orientation.”

Those cases included Oncale v. Sundowner from 1998, in which the Supreme Court ruled that same-sex harassment is sex discrimination under Title VII. Justice Antonin Scalia wrote for the majority that this wasn’t the problem Congress was addressing, but “statutory prohibitions often go beyond the principal evil to cover reasonably comparable evils, and it is ultimately the provisions of our laws rather than the principal concerns of our legislators by which we are governed.”

Another case Norcross cited in the appeal is Heller v. Columbia Edgewater Country Club, in which the court wrote, “If an employer subjected a heterosexual employee to the sort of abuse allegedly endured by Heller — including numerous unwanted offensive comments regarding her sex life — the evidence would be sufficient to state a claim for violation of Title VII. The result should not differ simply because the victim of the harassment is homosexual.”

Norcross said he recently received the go-ahead from a federal EEOC administrative law judge to work out the complaints before going to court. But he will take the case to court if the issues aren’t resolved in arbitration.

While penalties assessed in such cases are usually monetary, Norcross said the people who harassed and bullied Almodovar at work could be prosecuted for assault, a state charge that could be filed in federal court.

Almodovar has solicited statements from some fellow employees that corroborated his story.

One co-worker called him “knowledgable and shy” and said the chief often called him a “fag,” in violation of the Navy’s no tolerance policy. Another wrote about having seen Almodovar “being abused,” saying that others in the office “were messing with him.” That same person described Almodovar as “a pleasure to work with.”

And another former coworker called Almodovar “professional, knowledgable and among our most reliable IT representatives.” That co-worker then recalled how Almodovar worked out and lost weight, but was then harassed for that, too.

Almodovar said the rising level of bullying over the years might have been retaliation for him having reported to the Office of the Inspector General that one of his coworkers — someone who often called him “fag” — didn’t have the “secret clearance” necessary for the job he was doing. That man no longer works at the base.

Almodovar said he also reported to officials after discovering that four or five people at the fire station, including the fire chief, had fake college degrees they had paid for. Those individuals claimed they didn’t realize the degrees were not authentic, and after that, Almodovar said, the harassment against him increased.

Norcross said his client put up with the abuse because he had to “in order to keep his job.”

Now, though, Almodovar has no interest in going back to work at NAS Fort Worth. He’s been working at the Bush Presidential Center where, he said, everyone from the former president to his supervisors and co-workers are very pleasant. He said neither his weight nor his sexual orientation is an issue in his new job; he’s judged only by the work he produces.

But what Almodovar would like to see — among other things — is the Navy issue him a letter of apology and a good reference, and then put letters in the files of those who were bullying him.

“I want the chief to know what they did was wrong,” he said.

Almodovar said he wants to publicly shame base officials for allowing the harassment and bullying happen to him, because if it happened to him, it was and is happening to others.

“They need to do something when someone reports something,” he said.

Norcross said the case will probably take a year or two to be resolved.

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition August 12, 2016.