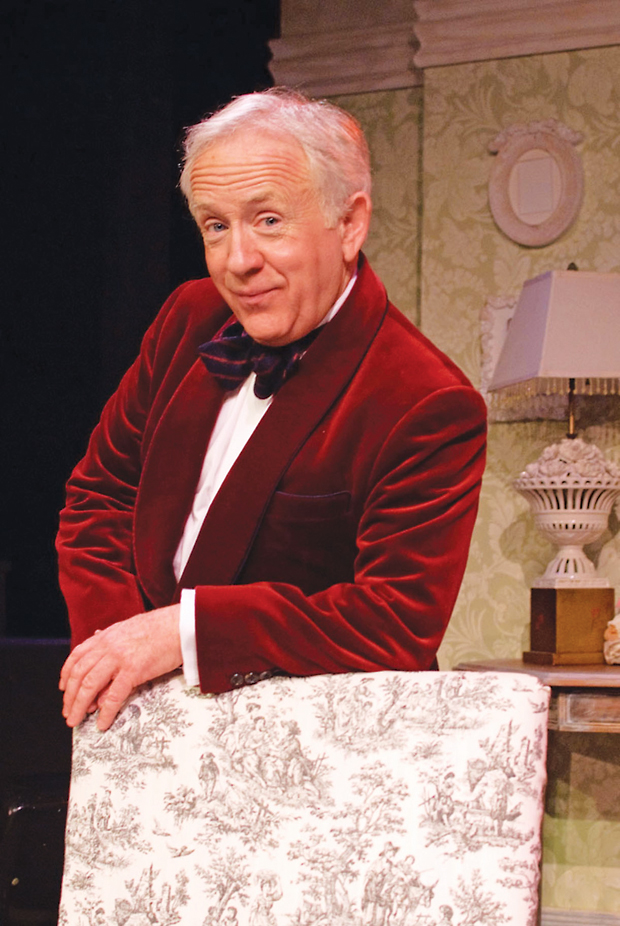

In his new show ‘Fruit Fly,’ pixieish comic actor Leslie Jordan finally answers the age-old question: Do gay men grow up to be their own mothers?

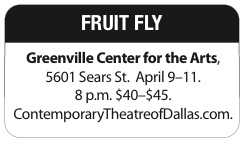

DON’T TELL MAMA | Leslie Jordan’s latest one-man show, ‘Fruit Fly,’ will be performed for the first time ever outside L.A. during a three-night run at the Contemporary Theatre of Dallas.

ARNOLD WAYNE JONES | Life+Style Editor

Leslie Jordan has been making his living as an entertainer for so long, something’s become patently clear: He just doesn’t give a shit.

Not that he ever did. But at 56, the pixieish actor — perhaps best known for his Emmy Award-winning performance as the fey socialite Beverly Leslie on Will & Grace — has finally reached a point where he can be up-front about that.

“I’ve been able to turn everything I was ashamed of as a kid to be an asset,” he says from a hotel room in Savannah, Ga., a week before bringing his one-man show, Fruit Fly, to Dallas. “I was ashamed of being a sissy. I went on TV and they paid me a lot of money to be one — the bigger the sissy the more money!”

Starting with a bit part on The Fall Guy 25 years ago and continuing through guest shots on series like Lois & Clark, Caroline in the City and Desperate Housewives, Jordan has paid his dues. But he really hit the big time last year with a featured role in the Oscar-winning smash The Help. It was the culmination of a career bracketed by many brushes with greatness.

“Tate Taylor, the writer and director [of The Help], who was in the L.A. production of Southern Baptist Sissies, called and offered me the part! No audition or anything. I’m used to low-budget movies and suddenly we have $35 million on DreamWorks’ dime with a two-week rehearsal period. At the read-through, I looked and saw Viola Davis on my right, scribbling on her script. Then I look at Sissy Spacek on the other side, scribbling away. I thought, well, I guess I better start scribbling!”

But the big moment came more than a year later, when he saw Taylor escorting Octavia Spencer up the steps to receive her Oscar. “I couldn’t wrap my mind around that,” he admits. “But what I’m really waiting on is, people keep telling me I’m gonna get a check for the DVD sales. I hear it’ll be big.”

But the big moment came more than a year later, when he saw Taylor escorting Octavia Spencer up the steps to receive her Oscar. “I couldn’t wrap my mind around that,” he admits. “But what I’m really waiting on is, people keep telling me I’m gonna get a check for the DVD sales. I hear it’ll be big.”

All of which has afforded Jordan the luxury of doing what he wants to do. While best known as an actor, Jordan wrote the dishy memoir My Trip Down the Pink Carpet, and has performed in several one-man plays he wrote about his experiences in life and show business. After taking his stage version of Pink Carpet to London’s West End, Jordan decided to concentrate on doing standup.

“I do think of myself as a writer, but I’m not like my friend Del Shores, who is so prolific he can write eight hours at a stretch,” he says. “Plus, I can only write for myself. And there’s nothing left! I’ve said it all.”

The last year, Jordan got booked in Los Angeles on the condition he perform all-new material. “I started thinking about my mother and how she had this box of slides. My mom was the last of nine and my dad was the baby of his family, too, so when the babies had a baby, I was photographed relentlessly.”

That became the basis for Fruit Fly, in which Jordan finally answers the age-old question: Do gay men become their mothers?

“On this one, I really concentrated on my mom. My parents were so young we never stayed at home. Mother was always the den mother of the Cub Scouts and real involved in my life,” he says. “How wonderful it was. And I have all these pictures of them.”

The slides, still in pristine condition, provided the launching point for this performance, which has never been performed outside of L.A. He’s nervous about that, if excited to be returning to his North Texas. (“I love Dallas, but I will be staying in Fort Worth,” he confesses. “I like Fort Worth more because of the cowboys walking around on Sundance Square.”)

Fruit Fly is a unique experience for Jordan, in part because he went in knowing what he wanted to accomplish.

“This is the first time I sat down to write a piece where I had a clear idea about a throughline and what it was about. This was very concise. Begins with me and my mother and is very intimate — I talk right to the audience.”

As a recovering addict, it’s important to Jordan that he share his truth with other people, and a show like this would seem to be the ideal medium for it. But he’s the first to admit after years of outrageous Southern storytelling, he’s no longer totally sure what the truth is.

“It’s all glommed together,” he concedes. “There’s always a kernel. But I’ll hear something about a friend and I’ll make it about me. Del [Shores] will sit there with an open mouth as I recount his stories as my own, but he never calls me out on it.”

That of necessity means you have to take what Jordan says with a grain of salt. But that don’t-give-a-shit mentality also means when he does say something, it’s not softened. Last year, he did a Broadway-bound musical with Varla Jean Merman, Lucky Guy, which he describes as “the worst experience of my life” and “a gilded turd.”

“That show has been around so long, Faith Prince was the original ingénue,” he says. “The lesson learned was I need to write my own stuff.”

Even so, his success is still a puzzle to him.

“I just lived the most blessed life. But who wants to hear your own voice, especially when you sound as nelly as I do?” he says. “I have no idea why people want to listen to me.”

But we do, Leslie. We do.

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition April 6, 2012.

Love me some Leslie Jordan! Go to this show. It is brilliant!

Leslie will made you LAUGH and you will see something we gays have in common. Injoy

Leslie Jordan is hot.

Leslie, if you are staying in ft. worth, i want to have lunch or brunch or a cup of coffee! best of luck with this show. i know it will be great!!