‘Berlin 1936’ is nonfiction that reads like a horror novel

‘Berlin 1936’ is nonfiction that reads like a horror novel

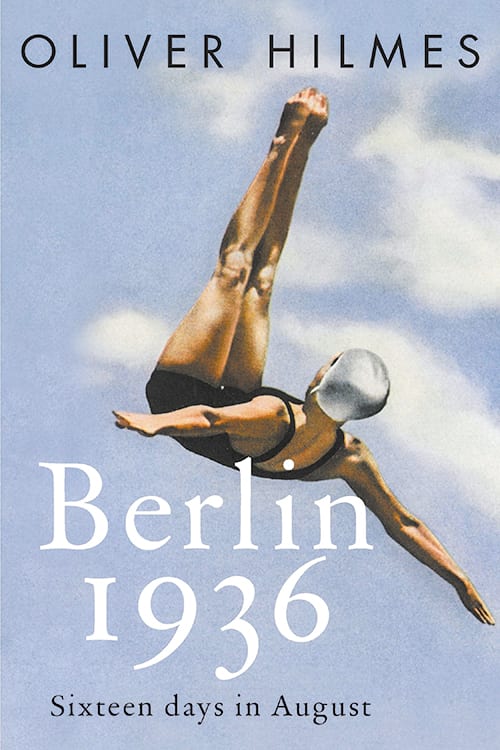

Berlin 1936 by Oliver Hilmes, translated from the German by Jefferson Chase (Other Press 2016/2018) $25.95; 320 pp.

It’s the first day of the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games, and composer Richard Strauss is impatient. He hates sports and he hates the tax that’s been enacted for this sporting event. For the hymn he writes on behalf of it, he demands 10,000 reichsmarks, and it rankles him that he ends up taking less.

Tom Wolfe has been to Berlin many times, and he couldn’t pass up a chance to see the Olympics there. Berlin is vibrant and friendly, and Berliners love the American novelist. He loves them… until a society matron whispers secrets in his ear.

On the second day of the games, Toni Kellner is found dead in her apartment. She was not a social woman — in fact, she was not a woman at all, and Nazi-enforced edicts made her afraid to seek help for her bad heart. Berlin used to have a thriving gay community, but the Third Reich is über-aware of gay men and people like Toni now.

Joseph Goebbels can’t stop thinking about the trouble his wife put him in. Not only did she have an affair with a swindler some years ago, but something else recently came to light: the Nazi Minister of Propaganda’s wife was the child of a Jewish man.

Jesse Owens won gold. And again. And again. And again.

By the eighth day of the Olympics, the city’s Roma and Sinti populations are taken from their apartments and moved to a sliver of land near a sanitation field. Most of them will die in concentration camps similar to the one being built just forty minutes away by local train.

And by the end of the Olympics, Hitler “is already determined to go to war.”

It may seem trite to say that Berlin 1936 reads like a novel, but it does. Indeed, it’s nonfiction that plays out like a horror novel, with a swirl of unaware and innocent victims, ruthless killers and a stunning, invisible stream of ice just beneath its surface.

The compelling thing about that is that it’s not one large tale of the Nazis and the games; instead, it’s as if author Oliver Hilmes starts with major historical figures and adds little advent-calendar windows with real people inside: here’s the Roma child, snatched from her bed; there’s the terrified, ailing transvestite; here’s the American woman who kissed Hitler; there’s the Romanian Jew who owns a thriving nightclub; all in the middle of an international story that readers know is only the beginning.

How could you resist? Don’t even try. Instead, just take Berlin 1936 to a corner and don’t count on coming out for a good, long time. Start this book, and you’ll want to just be left alone.

— Terri Schlichenmeyer