2 acclaimed artists — once-popular Castiglione and shadowy Caillebotte — provide for a fanciful exploration of art and mind at the Kimbell

David Taffet | Senior Staff Writer

taffet@dallasvoice.com

Some artists are household names; some remain forever relegated to obscurity. But Fort Worth’s Kimbell Art Museum — in two exhibitions, both playing now through Valentine’s Day — prove that fame isn’t the only indicator of genius.

Castiglione

Castiglione was one of the most sough- after artists of his time. By the time of his death in 1664, most of his work was in private collections. King George III acquired 260 of Castiglione’s works in 1762 and they have been stored at Windsor Castle ever since where this largest collection of the artist’s work in the world has been protected from light and the elements and remains in crisp condition.

The master is less well-known today (the Kimbell’s exhibit catalogue is only the fourth book ever printed about the artist), but his collection shows how innovative Castiglione was, and how his process remains impressive today.

Castiglione is the only artist who used oil paint on unprimed paper to create what can only be described as graphic images, not paintings. No one else did that — or has ever done it. Martin Clayton, curator for the Royal Collection Trust, says this is the first time some of these graphics have ever been exhibited.

Clayton credits much of Castiglione’s obscurity to his violent temper. He confronted and offended people with no regard to their position, and most of what is known about the artist is revealed in court documents related to lawsuits filed against him. Since the drawings are not dated, Clayton has spent years cataloguing the collection, arranging them by period. Clayton was in Fort Worth for the installation and opening of the exhibit.

As Castiglione aged and suffered from gout, he was unable to draw the sharp lines of his earlier works, so he began adding some color to his palette. The rich works are even more impressive, Clayton notes, because there’s no evidence of any pencil sketching beneath the painted lines.

Unlike any of his contemporaries, these sketches were not studies for eventual larger oils on canvas. Each is a completed work in its own right. (While Castiglione did oils on canvas, curator Timothy Standring from the Denver Art Museum — who managed the Kimbell installation — calls those pieces “nothing remarkable.”)

The 90 works on display comprise the first graphic arts installation in the space designed for that purpose in the new Renzo Piano Pavilion at the Kimbell Art Museum. Standring notes the significance of this fact: the artist (Castiglione) and the architect (Piano) were both Genoese.

Caillebotte

You may not be familiar with the artist, but you know the paintings: Fans of the Kimbell’s permanent collection know Caillebotte’s On the Pont de l’Europe, a bold look at modern life in Paris that has been a favorite in the museum for decades.

But the artist himself remains relatively unknown among the giants of Impressionism because a large portion of his work remains in private collections; about half of the current exhibit has never been shown before.

And because so little is known about him, the mystery remains: Was Caillebotte gay?

There’s some suggestion he was. The artist never married, lived with his mother until he was almost 40, and although he left much of his estate to a woman said to be his mistress, nothing is known about her — she may have been a housekeeper.

There’s also the issue of his subjects. Best known among Caillebotte’s work are his Parisian street scenes from the 1880s. Caillebotte’s portraits are mostly of well-dressed men. His Paris streets are filled with men and just a few women. Even his pastoral scenes on the Yerres River and at his home at Argenteuil depict men rowing or sailing.

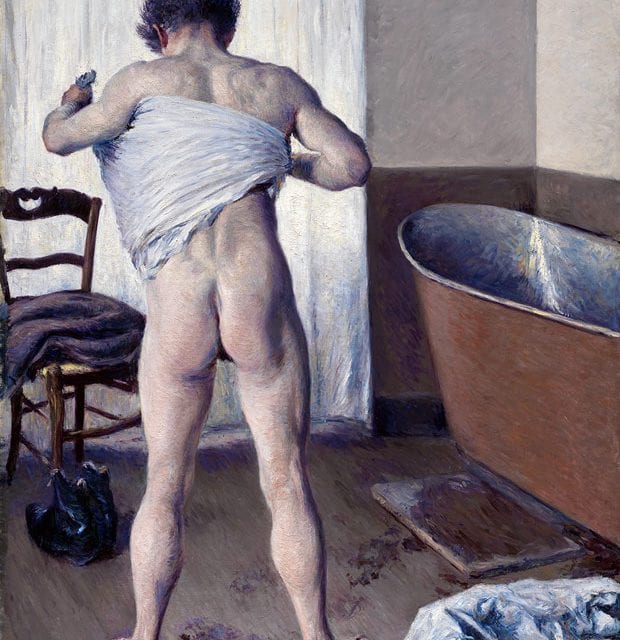

Richard Gallo is a repeated subject, such as in Richard Gallo and his Dog. Here, Gallo could be any gay man walking along the river spending the day with his dog. The most obvious clue in a painting may be At a Café. Here, one man in the cafe is checking out another man with mirrors used to make it clear there’s no woman off to the side that’s the real object of his ogling. His male nudes were rarely exhibited during his life and went into private collections. Exhibiting them might have been too racy for the age. Or maybe they might have revealed too much about the artist.

But there’s much on the canvasses here to keep the eye engaged. Caillebotte uses some techniques of the Impressionists — some dashes of color that brilliantly come together when viewed from across the room. But what distinguishes many of his canvases are wide angles and deep focus that can be compared to photography.

Man on a Balcony shows the subject from behind. The verdant trees and Paris apartment buildings beyond the balcony are the real subject and focus of the work. What draws you into his portraits isn’t the person as much as the furnishings. Caillebotte didn’t take commissions, so he wasn’t required to pander to the vanity of his subject, explains museum director Eric Lee.

Portrait of Richard Gallo is a good example. Here’s a good-looking, well-groomed man dressed in a black suit with his arms crossed. What makes the painting such a luscious work, however, is the overstuffed sofa upholstered in a red and green striped fabric highlighted with gold brocade. In Portrait of Monsieur R, Caillebotte goes even further. The blue and white stripe and pattern fabric is duplicated in the wallpaper. Monsieur R may almost be an afterthought to the boldly decorated room.

Because Caillebotte came from a wealthy family, he never relied on his art to support himself. As much as his own work stands on its own as a wonderful contribution to French Impressionism, his importance to the art world might be as a benefactor to other Impressionists. Upon his death, he left his collection of Monets, Manets, Renoirs, Cezannes and more to France, which formed the collection that became the Musee d’Orsay.

Kimbell Art Museum, 3333 Camp Bowie Blvd., Fort Worth. Through Feb. 14. KimbellArt.org.

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition November 27, 2015.