In Soldarity marching in Dallas

Text and Photos by Steven Monacelli

Dallas Voice Contributor

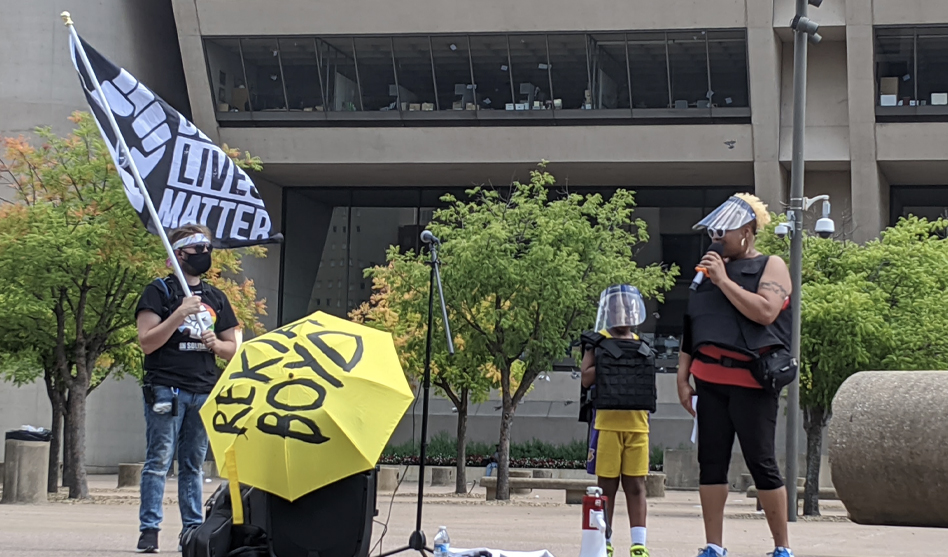

Despite the triple-digit heat, more than 200 people gathered at Dallas City Hall on Sunday, Aug. 9, for the Dallas Against White Supremacy rally and march, marking the 73rd day of consecutive protests here against police brutality and political repression.

The event was staged by an LGBTQ-led orgaziation known as In Solidarity. In Solidarity is not a new group; originally started in 2016, the group has organized a number of actions, including this year’s Pride March and a protest against Mike Pence during the vice president’s visit to Dallas on June 28, the 51st anniversary of the Stonewall Riots.

Planning for the Dallas Against White Supremacy rally was already underway when a pitstop by a so-called Back the Blue caravan at Friendship-West Baptist Church, an Oak Cliff church well known for its support of the Black Lives Matter movement, sparked controversy. Although caravan organizers said they had gotten permission to use the church’s parking lot as a rest stop, but Friendship’s pastor the Rev. Frederick Douglass Haynes III, said the caravaners had misrepresented themselves to church staff and called the event “a Klan rally.”

The event at the church galvanized many in the community against white supremacist intimidation and likely increased attention in and attendance at Sunday’s protest.

Calls for an All Lives Matter counter-rally emerged online as the In Solidarity event was being planned. But the counter-rally was ultimately cancelledat the last moment. As a result, the protesters gathered for the In Solidarity protest dramatically outnumbered the small group of heavily-armed individuals, affiliated with the 3 Percenter right-wing militia movement, that showed up in opposition.

Before the rally and march began, a sizable group of protesters stood face-to-face with the 3 Percenters and engaged in a lengthy dialogue. Unlike the similar scene in Weatherford recently where protesters, right-wing counter-protesters, and police ultimately engaged in physical altercations around a Confederate monument, there was no violence in Dallas. Individuals on both sides of the protest line were open carrying rifles and holstered pistols — seemingly prepared for the worst — but neither blows nor bullets were traded — only heated words.

The In Solidarity rally began with a performance by local musician Palmer, followed by a speech by Dr. Pamela Grayson, a member of FriendShip-West Baptist Church and director of the Collective Action Social Justice Coordination Center.

Grayson said she was proud of the community for coming together to stand up against white supremacy, describing the necessity of their coalition: “If we come together, we can strike a bigger blow. We need each other.”

Speakers representing a range of groups echoed Grayson’s message. Leroy Pena, national director of the Red Handed Warrior Society, put it plainly. He said, “When we talk about ending white supremacy, this is how we do it — a mix of different people coming together, forming alliances and saying they’re tired with this system.”

When organizers and activists heard that white supremacists were once again coming to their city, they heeded the call, no matter how last minute. Tramonica Brown, founder of the Dallas-based Not My Son protest and social justice organization, had come directly from church to attend. She told those gathered for the event,“There was so much hate building today, and I didn’t have time to change out of my Sunday best.”

Yet white supremacy was only one of the issues on the agenda. With the expiration of the CARES Act and the looming threat of mass evictions, one protester took to the microphone to deliver an impassioned speech, placing the fight in a broader context: “We are about to have 50 million people on the streets, and a pandemic is still going on. … I’ll be on the front line. Will you be with me?”

When the status quo reality is that Black and brown families and individuals are disproportionately at risk for food insecurity and homelessness, the looming crises are only likely to compound them in a similarly disproportionate fashion.

Eric Ramsey, an organizer with In Solidarity, said the goal the event was to “help create a platform and bring together a coalition of other protest and social justice organizations. We want to help keep the energy up.”

Indeed, waning coverage of protests on the nightly news broadcasts does not reflect the remarkable consistency and persistence with which protests have occurred in Dallas. Not every protest is thousands or even hundreds strong — sometimes there are less than 20 marchers —but it does not take thousands to block traffic and make their message heard.

On Saturday, Central Track reported a group of protesters blocking northbound traffic on Central Expressway, with others draping a banner from an overpass declaring “Black Lives Matter Every Damn Day.”

Though protests vary in size and tactics, they are a part of a broader strategy: Keep consistent pressure on.

At the end of the rally outside City Hall, hundreds took to the streets — safely and unimpeded — once again demonstrating that a protest does necessitate a riot. At the front, organizers with In Solidarity led chants aimed to send a clear message to all those who seek to intimidate them: “When Black lives are under attack, what do we do? Fist up, fight back!”

Palmer

Pamela Grayson

LOVED TO BE THERE! Insanely grateful for everyone who endured the heat. Big thank you for all who attended AND HELPED make it easier for others to attend! Love to all!