Alan Ross fought the city for years for a permanent remembrance in Lee Park

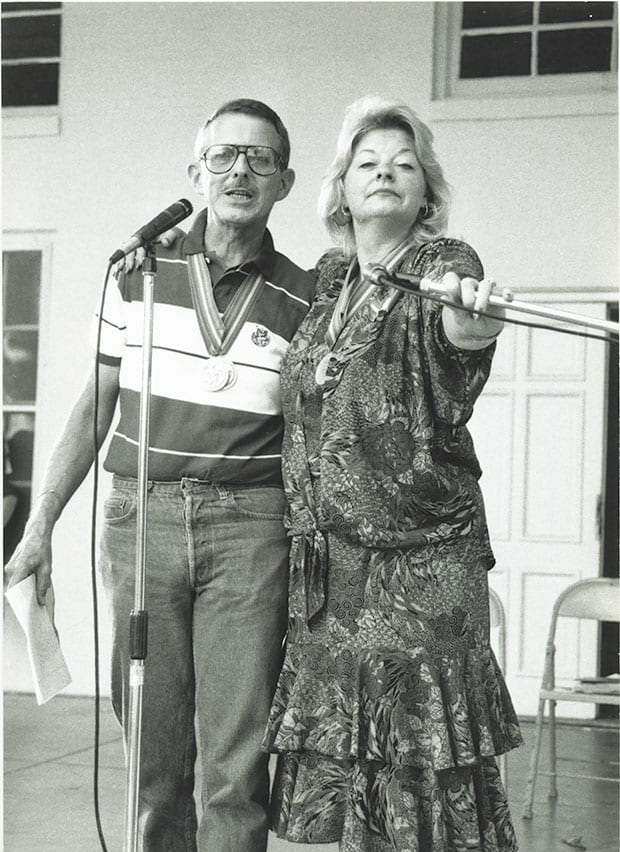

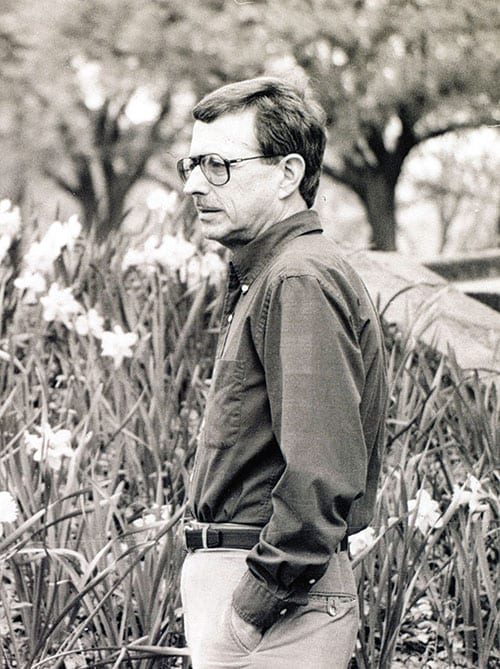

Left, Alan Ross and Lory Masters were grand marshals of Dallas Pride parade in 1986. Below, Alan Ross planted 1,000 daffodils in Lee Park as the first AIDS Memorial.

DAVID TAFFET | Senior Staff Writer

Friends will gather in Lee Park on March 18 at 11 a.m. to mark the 25th anniversary of the planting of a tree and placing of a plaque — the AIDS memorial that Alan Ross fought so hard to get placed in the park.

“The original tree died after 12 or 13 years,” said current Dallas Tavern Guild Executive Director Michael Doughman. And then the entire memorial was rebuilt nearby and given a larger location.

“They were re-landscaping in that area,” Doughman said, explaining the move.

“They were re-landscaping in that area,” Doughman said, explaining the move.

Although the plaque has been moved to a different location to make way for a new fountain, the memorial has stood, in one form or another, since March 1992. It was finally created after years of battling the city officials, who agreed at one point to allow the memorial as long as the words “AIDS,” “gay” and “lesbian” were not part of it.

But Ross, who was usually a very mild-mannered and patient person, refused to build an AIDS memorial that didn’t mention AIDS. He began his quest to have a memorial to those who died of AIDS in 1989, because, as executive director of the Dallas Tavern Guild, he had lost so many friends and colleagues to the disease.

Before there was a monument on the corner of Cedar Springs Road and Oak Lawn Avenue or an iconic location like the new Resource Center, Lee Park was the Dallas LGBT community’s place to gather. When the Texas sodomy law was declared unconstitutional by Judge Jerry Buchmeyer in 1984, the celebration was held in Lee Park. The next year, when a Pride parade became an annual event, it ended in Lee Park where awards for best entries were announced.

So Lee Park was the obvious place for the memorial.

Unfortunately, the Dallas Park board disagreed.

The original plan for the memorial would have included a time capsule and a walkway paved with bricks that had the names of each of the 1,000 people from Dallas that had died of AIDS at that time. The park board refused and the fight moved to the Dallas City Council.

The Dallas Southern Memorial Association — which raised $50,000 in 1936 to build the Robert E. Lee statue in the park, but by 1989 swore it had nothing to do with the Ku Klux Klan anymore — objected. They argued to the council that Lee Park was not a neighborhood park, but was there to pay tribute to Robert E. Lee.

That, of course, was a lie. The park was renamed in Lee’s honor after the Klan-related organization placed the statue of Lee. But Oak Lawn Park, as it was originally known, was already almost a half century old when that happened.

Also objecting to the council was the Turtle Creek Association. They said an AIDS memorial would make the park unsuitable for children. “The Park Board didn’t want to set precedent for putting that sort of memorial to one disease in a park,” Doughman said.

The Park Board suggested putting the memorial at Parkland Hospital. But Ross knew that was a horrible idea. He wouldn’t put his AIDS memorial at Parkland for the same reason the Kennedy memorial wasn’t placed at Parkland.

So he persisted and raised more than $20,000 for the park department to use for upkeep. Still, they resisted.

Meanwhile, the Park Board relented slightly. They’d allow a memorial that didn’t use the words “AIDS,” “gay” or “lesbian.” Ross was adamant the permanent memorial must include those words. Still, he planted 1,000 daffodils in a garden in Lee Park as the first AIDS memorial.

During that period, Dallas was required to change the way it voted for city council members. Instead of city-wide seats and large regional districts that were designed to prevent minorities from getting elected, the courts ordered single-member districts.

Although majority Hispanic and majority black districts were drawn, the city was determined to make sure the LGBT community would never be represented. The line between District 2 and District 14 was drawn down the middle of Cedar Springs Road, with the intention of diluting LGBT voting power.

That’s when the city got its first lesson in “don’t fuck with the LGBT community.” Two gay men, Chris Luna and Craig McDaniel, were elected to represent those districts, and Ross was ready to take his fight for an AIDS memorial to the new council.

Lee Park was in McDaniel’s district and he appointed a more neighborhood-friendly park board representative.

Ross planted his tree in March 1992 surrounded by other landscaping. A plaque with that date was placed in front of the tree in 1995, because of a continued battle with the city over wording.

The plaque reads: “This living tribute and surrounding beautification project is a gift to Lee Park and the City of Dallas in recognition of the AIDS community of Dallas County — Dallas Tavern Guild, sponsors.”

The current memorial is along a walk that begins at the new, formal entrance to Lee Park, at Lemmon Avenue and Turtle Creek Boulevard, then extends up to Arlington Hall.

And Lee Park is now operated by the Lee Park Conservancy, created in 1995 by five constituent groups. Among them is Dallas Tavern Guild. The others are Oak Lawn Forum, The Oak Lawn Committee as well as The Turtle Creek Association and Dallas Southern Memorial Association, which dropped their objections to the tribute to people who had died of the disease.

Alan Ross died of complications from AIDS on March 16, 1995, three years to the day after he planted the original tree as an AIDS memorial.

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition March 17, 2017.