Hate fired at the LGBT community has spurred us to fight for equality, but what do we do when it comes from within?

CAMOUFLAGED HATE | Internalized homophobia runs through the LGBT community like a high-voltage electrical current.

Editor’s Note: Some of the people interviewed for this story spoke on the condition of anonymity. Their names were changed.

At midnight on New Year’s Eve, Scott, a 28-year-old attorney, sent a three-letter text as balloons and confetti rained down on him at a private Dallas party. In seconds, the recipient replied with the same-worded text.

“It’s ‘wyb’, which is short for ‘who’s your buddy,’” Scott said. “We send that to each other a few times a day and especially when we can’t be together but wish we could be.”

For eight months, Scott and Alan have sent that message to each other hundreds of times by their own calculations as an expression of their feelings for one another. In the early weeks of the relationship, the message thrilled Scott, but lately, and especially on New Year’s Eve, it ignited other feelings.

“I was pissed,” he said. “I mean really pissed. I wanted to be with Alan on New Year’s, but he was at one party, and I was at another. You’d think we’re living in the 1950s. This is 2014, for crying out loud, and I can’t kiss the man I love on the one night that has so much symbolism for the hope of better things to come.”

Scott and Alan agreed to interview with Dallas Voice on the condition of anonymity, and during three meetings, they discussed their secret relationship and Alan’s closeted status and internalized homophobia, which he denies harboring. The contact was made through a mutual acquaintance, a Marine Corps officer, who has known Alan for three years.

“I don’t think I had ever heard of internalized homophobia until now,” Alan said. “It’s not something I have, so I don’t agree that’s the problem. I’m not out simply because of my job. Coming out would probably ruin my career.”

An executive with a Dallas-based professional sports organization, 32-year-old Alan has never been to a gay bar, has never attended a social event with a same-sex date and will only do things publicly with Scott that won’t be interpreted as a couple’s thing.

“We can go to a sports bar and have a beer, but we can’t go for a walk together,” Scott said. “I live with a long list of rules.”

Mental health professionals who treat LGBT issues would stamp Alan with one of the signs of internalized homophobia, regardless of his thoughts about it. In Beyond The Closet: The Transformation of Gay and Lesbian Life, author Steven Seidman describes being in the closet as a “life-shaping pattern of concealment.” Seidman writes that the closet seems to be on the wane, but it’s not gone, and its profound effects, including shame and homophobia, linger.

“Alan doesn’t realize it, but he’s put me in the closet, too,” Scott said. “I can’t go on a date with him because no one can see us out together like that, but I can’t go on a date with anyone else, either, because I’m with Alan, which makes no sense. This isn’t the way I want to live. I don’t do well with concealment.”

Scott and Alan, who both live in Dallas, met in San Diego while playing touch football at Balboa Park. Scott was on vacation, and Alan was on an extended business trip. Both share a love of sports, and upon returning to Dallas, they attended a few sporting events together.

“I wasn’t sure if he was gay,” Scott said. “We talked about sports and our jobs, safe subjects. I was hoping he was gay, so I carefully asked questions that would give me a hint. It wasn’t easy because Alan wouldn’t reveal hardly anything. He said he wasn’t dating because he was so busy with his job.”

Bingo. Sociologists and mental health professionals who treat and write about internalized homophobia say gay men and lesbians often use the demands of their jobs as an excuse not to pursue romantic involvements. They believe it keeps them safe from the toils of dealing with who they are.

“Most of us are concerned at one time or another with feeling bad about being gay or lesbian,” said Candy Marcum, a community counselor and president of Stonewall Behavioral Health. “It has to do with incorporating messages that say it’s not good or it’s even bad to be gay or lesbian. Those messages come from our families, the church, friends and the media, and they can linger into adulthood.”

Internalized homophobia takes root in those messages and leads to being closeted and a profusion of other traits that ravage a person’s self-esteem, among them contempt for the more open members of the LGBT community. The problem also seeps into the decisions community leaders make, such as the recent decision of ILSb/ICBB, a locally based leather organization, to restrict eligibility in a contest to biological males. The group later reversed its decision.

The issue also is complicated by the LGBT community’s many facets. Tension between gay men and lesbians sometimes surfaces, and there are individuals in both camps who are opposed to drag queens and trans people. In that regard, gays and lesbians are no different than the heterosexuals who burden the community with hate, counselors say.

“Internalized homophobia leads to gay-on-gay acts of meanness and rudeness,” Marcum said. “Those people tend to hurt other gays and lesbians.”

The development of a scale to measure that internalized homophobia, written about in the Oxford Journals, suggests four dimensions to the issue: public identification with being gay, perception of stigma associated with being gay, degree of “social comfort” with other gay men and beliefs regarding the religious or moral acceptability of homosexuality.

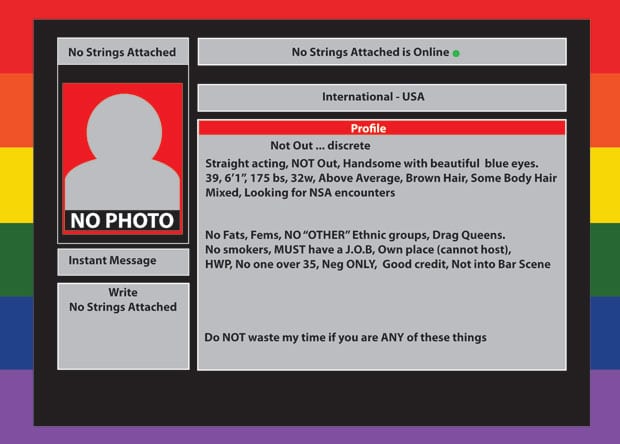

While the occurrence of internalized homophobia might be less among the millennials, that generation born between 1982 and the early 2000s, it still surfaces in their language and in the ads they post on social media apps such as Grindr, Scruff and Craigslist.

They’re looking for “straight-acting” men, they say. No “fems” and they must be “discrete.”

“I don’t think that’s internalized homophobia,” Corey Wiseman said. “Those are just preferences. I’m not into fem guys, just like I’m not into older guys. Does that mean I hate older guys? No. It just means I don’t want to date them. I should be able to say I don’t want to date fem guys without being labeled as a homophobe.”

Still, the accusations fly through the community.

“I hate the word straight-acting,” David Lambert said. “It’s demeaning to us, as if straight is the behavior we should be working toward. It’s homophobic to use it because it’s saying there’s something wrong with being something other than ‘straight acting.’ It’s insulting.”

Scott, tangled in the complexities of Alan’s world, said he never gave internalized homophobia much thought until this relationship. He’s more aware now of the struggles some gay men face both as the targets of internalized homophobia and those who harbor it.

“I really didn’t know the extent of the problem until I had to deal with Alan’s refusal to come out and his idea that he’ll be professionally ruined if he does,” Scott said. “That whole industry (sports) is full of internalized homophobia, like that’s a secret. But I think that by staying closeted, they’re denying themselves so much power.”

One high-profile woman can relate to both Scott and Alan. Edie Windsor, the plaintiff in the case that led the U.S. Supreme Court to rule parts of DOMA unconstitutional, spoke publicly shortly after the decision, explaining her own struggle to speak honestly about her marriage with colleagues.

“Internalized homophobia is a big bitch,” she said.

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition January 3, 2014.

[polldaddy poll=7688482]