We may never know the full truth about the gender-bending Wild West icon

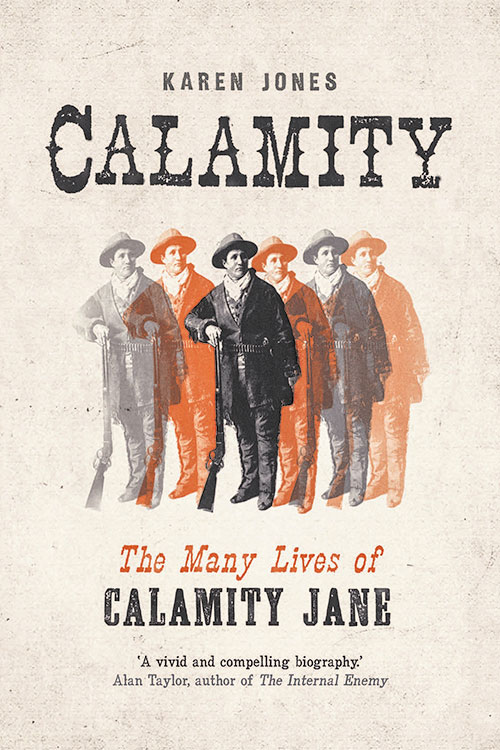

Calamity: The Many Lives of Calamity Jane by Karen R. Jones (Yale University Press 2020) $28; 303 pp.

You can call yourself whatever you want. Nobody says you can’t have a different name every day, if that’s your wish. Re-invent your life; create a new past; change your birth year, and tell new stories. Nobody cares if you do. Become whoever you want to be but, just know that, as in Calamity: The Many Lives of Calamity Jane, the truth might catch up.

When one thinks of women of the Wild West, the list is short, and Calamity Jane is toward the top. Born May 1, 1852, or possibly 1856, Martha Jane Canary was the oldest child of a gambler and a “woman of the lowest grade,” says Jones. Her parents left Missouri when Martha was a child and moved to Montana to take advantage of the gold rush there, but they didn’t even get a taste of its wealth before they both died.

When one thinks of women of the Wild West, the list is short, and Calamity Jane is toward the top. Born May 1, 1852, or possibly 1856, Martha Jane Canary was the oldest child of a gambler and a “woman of the lowest grade,” says Jones. Her parents left Missouri when Martha was a child and moved to Montana to take advantage of the gold rush there, but they didn’t even get a taste of its wealth before they both died.

Martha was a teenager then, and, to her credit, she did whatever was needed to survive — never staying in one place for very long, living hand-to-mouth in what became a “pathologically itinerant lifestyle” that she maintained on and off for her whole life. It’s how she likely got her nickname: calamity followed her from campsite to saloon to jail cell.

By the time she was out of her teens, Calamity Jane’s reputation was as wide as the prairie. She boasted about having been a “female scout,” but some of her claims don’t follow facts. Canary said that she drove stagecoaches and rode for the Pony Express, but dates don’t always match up. In early adulthood, she got into a habit of wearing men’s clothing, which caused scandal and titillation for much of her life and which led to genderfluidity today. There are so many instances where truth differs from legend, in fact, that we may never know the whole story about her.

It’s this aspect of Calamity that will keep you on your toes: As Jones sifts through the myths and mysteries of Canary’s life, we, too, begin to see not just a complex woman but also fascinating (for a western novel fan) slices of fiction-crushing facts about the Old West.

Perhaps not surprisingly, much of the former centers on Canary’s cross-dressing, which Jones admits was common in Canary’s day, and not just for her; the difference, perhaps, is that she was unabashed about it. Because she was an anomaly by way of reputation and fame, Old West denizens gossiped about Canary; newspaper accounts mention her mode of dress quite often, and Jones hints at unknowns in her gender identity. Since Canary loved to embellish and because she seemed comfortable with a foot in many worlds, concrete evidence either way is elusively slippery.

Hollywoodization aside — and there’s plenty of that when it comes to Calamity Jane — it seems that the question may remain open. As for something that pulls this tale all together, though, and offers tantalizing reading, find Calamity and call it good.

— Terri Schlichenmeyer