Matt Lyle set his new clash-of-cultures comedy in the heart of Dallas’ gayborhood

ARNOLD WAYNE JONES | Executive Editor

jones@dallasvoice.com

If you’re a fan of theater and of comedy and you live in Dallas, then you certainly need to know who Matt Lyle is. For more than a decade, he’s been one of the most consistently funny playwrights around. His paean to silent films, The Boxer, recently enjoyed its 10-year restaging at the Festival of Independent Theaters; Hello Human Female brilliantly zings sci-fi and romantic comedy; Kitchen Dog Theatre’s production of his Barbecue Apocalypse is still remembered as one of the most hilariously perverse satires to come down the pike. He has carved out a unique niche, midway between Eugene O’Neill and Eugene Levy.

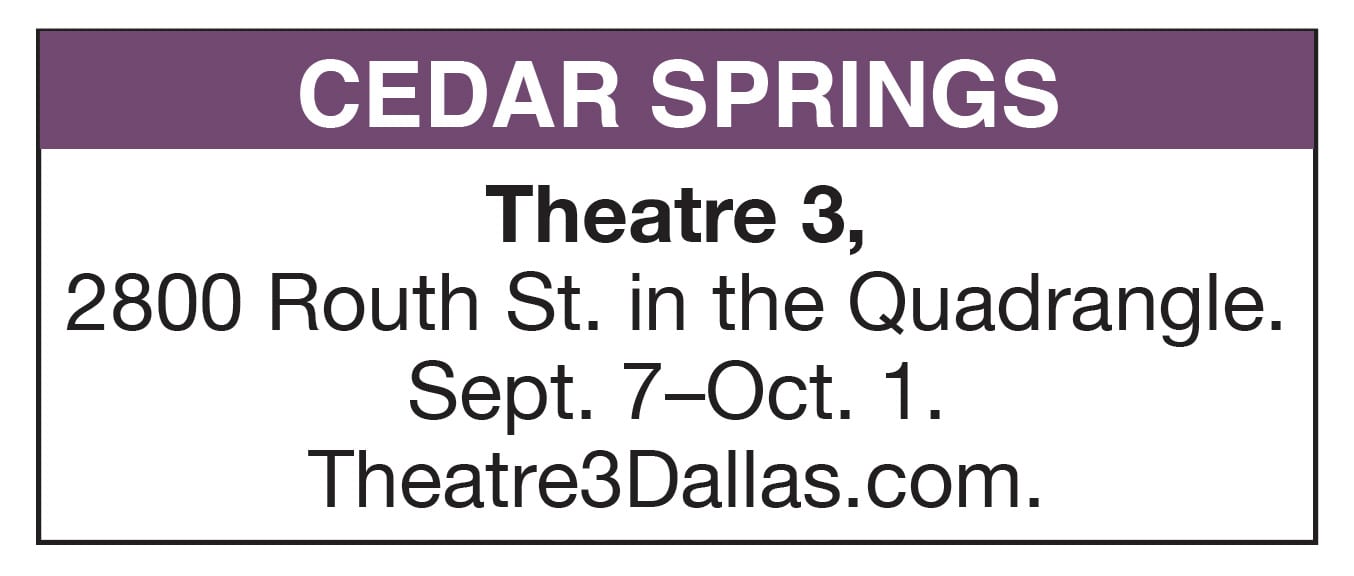

And now Matt Lyle has turned his sights on the gayborhood. His latest produced play — provocatively titled Cedar Springs; or Big Scary Animals — opens Thursday in the downstairs space at Theatre 3. Despite its satiric backdrop, Lyle calls it “a comedy with high stakes. The situation is about as realistic as anything I have written. It has the pace and timing of a comedy, but it’s about serious things.”

And now Matt Lyle has turned his sights on the gayborhood. His latest produced play — provocatively titled Cedar Springs; or Big Scary Animals — opens Thursday in the downstairs space at Theatre 3. Despite its satiric backdrop, Lyle calls it “a comedy with high stakes. The situation is about as realistic as anything I have written. It has the pace and timing of a comedy, but it’s about serious things.”

The setting is a fictional condo located on Cedar Springs Road. Two sets of neighbors — one an interracial, gay male couple of lefties, the other white retirees who have moved from rural Texas to be near their grandchild — share a common wall. One day, the gay couple invites the heteros over for a get-to-know-each-other dinner. It does not go well.

Matt Lyle

The characters, if not the plot, are from experience. Lyle grew up in small-town East Texas, and so he lived with many of the more countrified folks with social blinders on. But he moved to Dallas as an adult, where his circle of friends included a rainbow of diverse backgrounds; his father-in-law is even gay, and Lyle and his wife Kim (herself a gifted comic actress) would often visit her dad in Oak Lawn. That formed the seed for setting the play in Boys Town.

The other trigger for Lyle was to address the insidiousness of social media and how it affects our sense of community responsibility. It’s much easier to be racist, or homophobic, or xenophobic, from the comfort of your smartphone; it’s a very different experience face-to-face.

“I’m really interested in how firmly we categorize each other,” Lyle says. “If you’re from the country, I can assume 90 percent of how you are — that same [if I know your] race, religious background, etc. People have always done that, but now we voice it very loudly. We all live with it. Most of the people in my Facebook feed feel the way I do. But 10 percent are having their beliefs reaffirmed by their groups.”

What happens, then, when those groups intersect in real life?

“My dad [was of the generation that] always said, don’t talk about religion or politics in mixed company,” Lyle says. “But what else is there to talk about at this point? There are Nazis walking in town squares! The play really wants to take everything we are now as modern people and put us in a room together and interact. I put situations in front of [the characters] where they are forced to reveal who they are and what they expect from each other. And that’s hard when every day there is a culture clash.”

Turning such fraught ideas into a comedy is a devilish exercise — and one thing that distinguishes Lyle’s work. He wants people to laugh. But he also knows that comedy is extremely subjective.

“I certainly have plenty of instances, whether in real life or in a play, where I think [about a joke], ‘This is the thing!’ … and then ….” crickets.

“Where I’ve gotten better as I’ve gotten older — in life and in writing for the stage — is that I’m not always trying to make a joke. I filter pretty well. It’s not like a CBS sitcom approach to writing, appealing to the least common denominator.”

One of the risks he’s taken with this play is setting it so firmly in Dallas’ gayborhood. When he started writing the play years ago, he chose to follow the dictum to “write what you know.”

“We go to the Pride parade every year and used to eat at the Bronx when it was open. Kim’s dad lived in the area before moving to Oak Cliff. So it made sense” to set it there. The address of the fake condo, for instance, is the address of the now-closed Black-eyed Pea, a sort of in-joke about the crossroads of country roots and gay culture in Dallas. Now that Lyle’s work is being produced outside of Texas, he realizes some of the references won’t necessarily land. “It’s pretty Dallas-specific — the [older couple is] from a real place; the Cowboys are pretty specifically mentioned. That’s a little bit of a gamble for me.” Then again, that’s one of the great things about getting to see its premiere.

Although the play takes a dark turn and “gets pretty intense,” Lyle likes to think that ultimately there’s an element of optimism.

“I have a 4-year-old, and I see how she has zero expectations of people based on their race or orientation,” he says. “I’m sort of a hopeful person. I think it’s a hopeful piece.”

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition September 01, 2017.