The national debate about removing Confederate memorials comes to Dallas

DAVID TAFFET | Senior Staff Writer

taffet@dallasvoice.com

The issue of memorializing the losing side of a civil war with monuments to its treasonous leaders has simmered for years. But as Nazis gathered in Charlottesville, Va., last weekend to defend these symbols of racism — shouting anti-gay, anti-black, anti-Semitic, anti-immigrant slogans and with one Nazi slamming his car into a group of counter-protesters, killing one and injuring 19 — the issue has come to a boiling point.

The events in Charlotte brought debate to the forefront in Dallas, and a rally is set for Saturday evening near one of the city’s monuments.

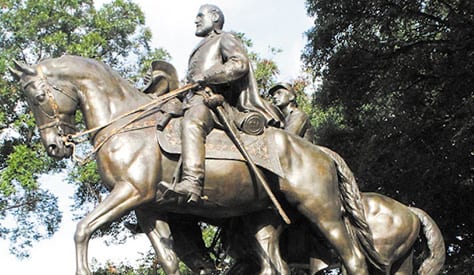

In Dallas, we have two problematic Confederate monuments. One stands on the edge of an historic cemetery at an entrance to the Dallas Convention Center. The other is in Lee Park in Oak Lawn.

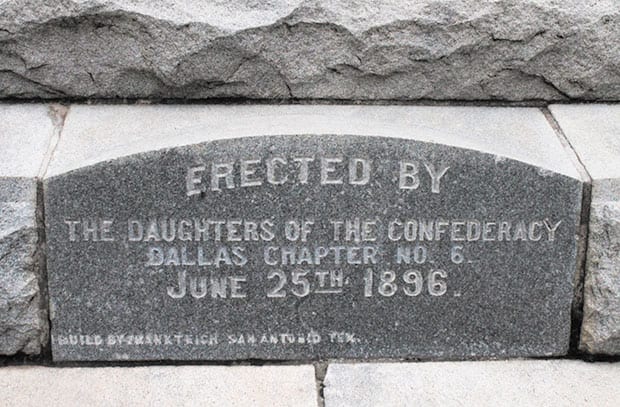

The Confederate memorial at the Dallas Convention Center was erected in 1896, 32 years after the end of the Civil War. It is the oldest public sculpture in the city. Originally located at Old City Park, it was moved to its current location in 1961, when construction on I-30 through downtown began.

The first piece of the convention center, Dallas Memorial Auditorium, was built in 1957, and the monument would have been about a block away at the time. Now it stands at an entrance to the facility.

In 1936, 72 years after the end of the Civil War, Oak Lawn Park was renamed Lee Park. A statue of Robert E. Lee was installed, and a two-thirds size replica of his home, Arlington Hall, was built.

In 1995, a public-private partnership was formed to manage Lee Park that included the Dallas Tavern Guild, the Oak Lawn Committee and Turtle Creek Association among others, including the Dallas Southern Memorial Association that commissioned and placed the statue in 1936 and was affiliated with the Ku Klux Klan at the time the statue was installed.

Mayor Mike Rawlings held a press conference on Tuesday, Aug. 15, to weigh in on the issue of whether those monuments should be removed from public display. While not directly calling for the immediate removal of the monuments, he did describe them as “problematic.”

“It’s easy to jump on the bandwagon to tear them down,” he said. “I hesitate. We’re better and stronger when not divided.”

Rawlings called for a task force to study the issue and report back to the city council in 90 days.

But Councilman Philip Kingston gathered five signatures to force the issue onto the Dallas City Council’s agenda.

“The council needs to voice its strong disapproval,” he said to send the task force a clear message of where the council stands.

Councilman Omar Narvaez said about the monuments, “What they mean today is what’s important.” And today, they’re a rallying cry for white supremacists.

One idea floated was to move the monuments elsewhere, but both councilmen made it clear that place shouldn’t be public property nor should they be maintained with public funds.

Rawlings asked Mary Pat Higgins, director of the Dallas Holocaust Museum Center for Education and Tolerance, to be part of the discussion.

Higgins said her participation was very new, and she wasn’t sure what her role was going to be. But she said she imagines the Holocaust Museum would be a source of education and reconciliation for the community.

One reporter at the press conference asked if the Holocaust Museum might be the place to move the monuments. But just the dimensions of the statues precluded them from even fitting in the building.

The Rev. Eric Folkerth, pastor of Northaven United Methodist Church, said he was disappointed the mayor didn’t clearly come out in favor of removal. “An issue like this calls for moral leadership,” he said. “That doesn’t preclude conversation, but leaders lead from their convictions.”

Folkerth said by not clearly laying out his position, the mayor could be creating a situation he wants to avoid. The conversation could easily devolve, he said.

“If Saturday [in Charlottesville] proved nothing else, it proved these monuments are revered by white supremacists,” Folkerth said. “As a white person whose relatives fought for the Confederacy, I am offended by that. I want my mayor and council to say the same.”

The Rev. Neil Cazares-Thomas, senior pastor of Cathedral of Hope, was born in England and views the issue from a European standpoint. He compared it to when Germany tore down the Berlin Wall and pieces were disseminated around the world.

Going back a generation farther in German history, he said Germany distances itself from Hitler and the Nazi period: There are no monuments to that dark era to be found in that country — or others.

“These are not monuments to heroes,” said divinity student Todd Whitley. “They’re monuments to the losing side.” He said people claim they feel as if they’re losing their identity, but he added, they say they’re “upholding history, but that’s code for what’s evil.”

While rallying around these Civil War monuments, the white supremacists were chanting anti-Muslim, anti-Jewish and anti-LGBT as well as racist slogans. “Nothing historical about their rants,” Whitley noted.

Confederate monument at Pioneer Park

Confederate monument at Pioneer Park

The Confederate monument was moved to the edge of the cemetery at Pioneer Park in 1961 before the main Dallas Convention Center was built. However, today it welcomes people as they enter the facility.

Pioneer Park is made up of four adjoining cemeteries that had all become city property by 1969. One was a Jewish cemetery, and the bodies from there were moved to the current Temple Emanu-el Cemetery on Lemmon Avenue at Central Expressway. The longhorn statues are situated partially on that portion of the park.

Some of the first burials in Dallas took place in areas of Pioneer Park that remain a cemetery. The gravestones highlight the city’s pioneering families with names such as Stemmons, Peak, Akard, Good, Latimer and Marsalis. But historical markers, mostly placed in the 1990s, highlight only those who served in the Confederacy.

For example, Trezevant Calhoun Hawpe was elected sheriff in 1850 and served two terms. In 1862, he organized and was first colonel in the 31st Texas Cavalry, and he is credited with winning the battle of Newtonia for the South. In 1863, he was stabbed to death by a friend on the county courthouse steps. Stand by his headstone and you’ll likely feel the earth churning as he rolls over in his grave knowing who his current successor is.

Barton Warren Stone was a farmer who originally opposed Texas secession but then organized and commanded two Texas cavalry regiments for the Confederacy. And John McClannahan Crockett was mayor of Dallas and then lieutenant governor of Texas during the Confederacy.

But those whose names we remember on our streets? Not a word about their contributions to the city from those same historians who chose to memorialize Confederate leaders.

Lee Park

More than just the statue of Robert E. Lee overlooking Turtle Creek is dedicated to the Confederate general. Arlington Hall is a replica of Lee’s home in Virginia and is part of the memorial to the Confederate general. While Arlington Hall stands as a monument to Lee, nowhere in the park is there an acknowledgment that the original plantation house was built and maintained by slaves.

In 1995, a coalition of community groups joined together to form the Lee Park Conservancy, and renovation and expansion of Arlington Hall was accomplished with private funds.

In 1995, a coalition of community groups joined together to form the Lee Park Conservancy, and renovation and expansion of Arlington Hall was accomplished with private funds.

Among the groups that formed the conservancy was Dallas Tavern Guild, the LGBT bar owners. According to Tavern Guild’s Executive Director Michael Doughman, the Tavern Guild has nothing to do with the operation of the park anymore. A few years ago, they replanted the Alan Ross memorial AIDS garden in the park, but any other connection ended when the Pride festival moved to Reverchon Park over space issues.

The Dallas Parks Department still provides maintenance service for the park, but doesn’t oversee the operation. The Lee Park Conservancy does.

While the city discusses removing monuments, some have suggested a simple first step in removing Confederate memorials would be to revert to the park’s original name — Oak Lawn Park.

And at the Capitol

Meanwhile, Confederate monuments remain standing around the state, including at the state Capitol. This week, state Rep. Eric Johnson, D-Dallas, sent a request to Texas State Preservation Board to remove a particularly offending plaque and other monuments at the Legislature. And, he said, if a second special session is held, he’ll file a resolution demanding their removal.

“I will be introducing a resolution to have this and all other such historically inaccurate and offensive Confederate iconography removed from the Texas Capitol and its grounds,” Johnson wrote. “It sure is great not having to check with any owners or handlers before I make a decision.”

The plaque Johnson is referring to was placed in the Capitol in 1959 by a group called Children of the Confederacy. Among the goals of the group, the plaque claims, is “to study and teach the truths of history (one of the most important of which is, that the war between the states was not a rebellion, nor was its underlying cause to sustain slavery).”

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition August 18, 2017.