LGBT authors Mark Segal and Tracy Baim bring their books on LGBT history — one a memoir, the other a biography — to Dallas

Tammye Nash | Managing Editor

There are certain buzzwords that even the most recently out person recognizes when it comes to LGBT history. “Stonewall,” of course, is the most obvious.

But it is the stories behind “the story” that so often get overlooked — the stories of the men and women who lived that history, who made that history, and who made it possible for our community to celebrate full marriage equality this year, with full equality finally a possibility on the horizon.

This fall, two of the most well-known writers and publishers in LGBT media have published books that look at some of the stories behind the story. And these two books are likely become required reading for anyone who is a student of history and anyone who just wants to know more about the road to equality.

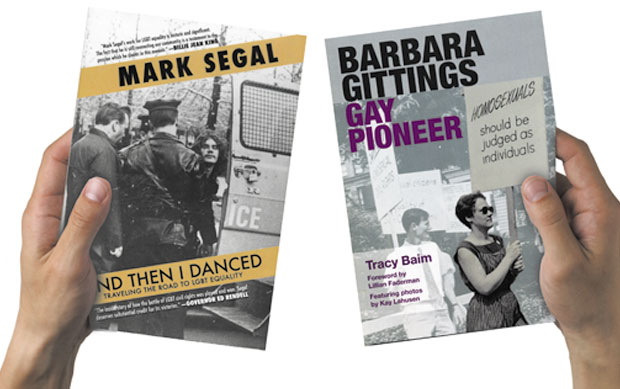

Tracy Baim, publisher and editor of Windy City Media Group, has authored Barbara Gittings, Gay Pioneer, a 235-page biography of the woman who worked side-by-side with Frank Kameny and who helped organize and stage the first LGBT protest outside the White House.

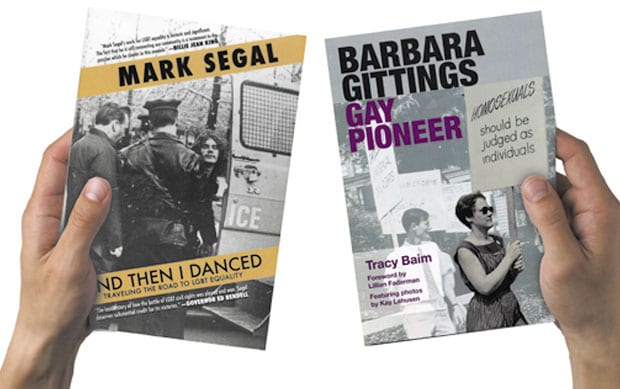

Mark Segal, founder and publisher of Philadelphia Gay News, has put pen to paper to chronicle his own life, from his childhood “on the wrong side of the tracks” in Philadelphia, to his presence at the Stonewall Inn in New York that fateful night in June, 1969, to his current efforts in politics and activism. His book is And Then I Danced: Traveling the Road to LGBT Equality.

Both Baim and Segal will be in Dallas to talk about and sign copies their books on Thursday, Nov. 5. The event begins at 7 p.m. at the Cathedral of Hope’s Interfaith Peace Chapel, 5910 Cedar Springs Road. Dallas Voice is presenting the book signing event, in cooperation with Cathedral of Hope and The Dallas Way. Voice staff members will moderate the discussion.

And Then I Danced

Segal’s memoir gets your attention quickly, as he details how his life changed when his father lost his neighborhood grocery store to eminent domain, and the family was forced to move to a housing project. Segal, an only child, learned early what it meant to be different and to struggle. But he also learned early, from his grandmother, suffragette Fannie Weinstein, what it meant to advocate for human rights.

In May 1960, at the age of 18, Segal moved alone to New York City, looking for someplace that he could be an openly gay man, looking for community and someplace to belong. A few days later, he stumbled across Greenwich Village bar called the Stonewall Inn and found what he was looking for.

And it was there he began a lifetime of activism.

Two years after the Stonewall Riots, Segal returned to Philadelphia to help his father care for his ailing mother, and continued his activist ways. It was then that, as a member of The Gay Raiders, he helped create “zaps,” non-violent protests intended to get the attention of organizations and institutions that were harmful to the LGBT community and its fight for equality in some way.

The most famous zap came on Dec. 11, 1973, in New York City when Segal and the Raiders, protesting a blatantly homophobic episode of Sanford and Son, managed to interrupt a broadcast of the CBS News with the legendary anchor Walter Cronkite.

Already one of the most out and most well-known gay rights activists in the country, that zap helped cement Segal’s place in LGBT history. He went on to found the Philadelphia Gay News, and to help found the National Gay Press Association and the National Gay Newspaper Guild, and to continue his role as an activist, pressing at the local, state and national level for LGBT equality.

Segal’s memoir is plainly written, although dense at times. He sometimes tends to veer off into details that might best have been, for clarity’s sake, left out. But at the same time, it is those details that help weave the rich background tapestry against which his life’s story unfold.

Barbara Gittings, Gay Pioneer

Baim, who co-founded Windy City Times newspaper in 1985 and Outlines magazine in 1987, worked with Barbara Gittings’ partner of 46 years, Kay Lahusen, to tell the story of the activist who was, a English professor and author Lillian Faderman wrote in her foreword to the book, a revolutionary who didn’t look like a revolutionary.

The book opens with Gittings’ birth, in Vienna, Austria, in 1932, and follows her development into one of the foremost architects of the early LGBT rights movement in the United States. By eighth grade, Gittings had begun to develop romantic feelings for other girls, and by high school, her teachers were remarking on her homosexual tendencies, even though Gittings herself remained largely unaware.

When a close platonic relationship with another girl in college prompted rumors that Gittings was a lesbian — again with Gittings herself being the last to know.

When she did hear about the rumors, from her dormitory director, Gittings went to a psychiatrist to get help. It was an experience that fueled her determination to fight against the psychiatric world’s classification of homosexuality as a disease or disorder.

Baim follows Gittings’ early years as an activist with the Daughters of Bilitis, through her activism and protests in Washington, D.C., New York and Philadelphia, to her work battling first the American Psychiatric Association and then the American Library Association.

There is a chapter on Gittings’ and Lahusen’s relationship and one on Gittings’ life in the public eye. It winds up with a chapter on what was, perhaps, her biggest fight — her battle against breast cancer, which eventually claimed her life, at age 74, in 2007.

Baim writes like the reporter she is — clearly and concisely. Her style makes the book an easy read, especially given the fact that the woman she writes about is so fascinating, and so important in the history of this community. And Lahusen’s input lends an authenticity and immediacy that might otherwise be missing.

In another nod to her journalistic background, Baim has included all the references necessary to back up her facts; the book includes a three-page bibliography, and an 11-plus-page index. The more than 270 photos provided put a very personal face to a name that has become a legend in LGBT activism.

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition October 30, 2015.