DTC’s world premiere musical ‘Fortress of Solitude’ explores a bromance derailed

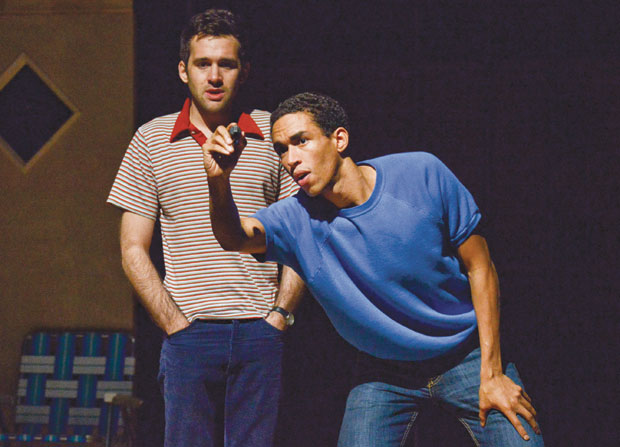

RACE RELATIONS | Two inner-city best friends — one white (Adam Chanler-Berat), one black (Kyle Beltran) — take vastly different paths in life in DTC’s premiere staging of ‘Fortress of Solitude,’ adapted from the best-selling novel. (Photo courtesy Karen Almond)

ARNOLD WAYNE JONES | Life+Style Editor

………………………………….

FORTRESS OF SOLITUDE

Wyly Theatre, 2400 Flora St. Through April 8.

DallasTheaterCenter.org.

………………………………….

Dylan (Adam Chanler-Berat) was one of those kids who was more his parents’ experiment than their child. They were hippie-dippy social pioneers, ones who moved into a dodgy neighborhood in 1970s Brooklyn so that Dylan could be exposed to different races and ethnicities, and not become a suburban robot. Mom (Patty Breckenridge), though, couldn’t hack motherhood and cut out when Dylan was 14; Dad (Alex Organ), so wounded by her departure, retreated into his own world and barely acknowledged Dylan. So it was up to him to forage a life on his own.

That meant navigating past the neighborhood bully (Nicholas Christopher), tolerating the only other white kid on the block, a nebbish named Arthur (Etai Benshlomo) and, to his surprise, befriending an introspective black kid name Mingus (Kyle Beltran). Dylan and Mingus, despite their backgrounds, shared a lot in common, including a love of comic books and an appreciation for music; Mingus was, after all, named after jazz great Charles, a sign of respect from his dad Barrett (Kevin Mambo), himself a minor hitmaker in an R&B vocal group.

That’s the backdrop for Fortress of Solitude, a world premiere now at the Dallas Theater Center, based on Jonathan Lethem’s semi-autobiographical novel. Part In the Heights, part Jersey Boys, and a whole lot of its own creativity, thanks to Michael Friedman’s protean score, it’s a stirring and reflective musical about the American experience, as rich as four-part harmonies.

As with Michael Chabon’s The Adventures of Kavalier and Clay, comic books play a central role in the lives of two young men. Both motherless with remote fathers, they identify with the orphan origin stories of their favorite characters (on the beautiful, bromantic “Superman”) and their friendship blossoms. But just how far does it go?

That’s a central mystery of Fortress, which strongly suggests, but never shows, that Dylan and Mingus are more than just friends, that they love each other not just in the playground-bonding sense but honestly, and deeply. That’s what makes the inevitable split — Dylan gets admitted into a magnet school in another neighborhood, Mingus is forced to fend for himself in the ’hood — more poignant than just growing apart. Each oversight is an infidelity, and the pain never goes away.

Fortress of Solitude is almost too smart, too introspective, to adapt for the stage, not alone as a musical, but Itamar Moses’ script does an admirable job. When Mingus resorts to dealing drugs to get by, he repeatedly assures Dylan that “It’s what I do, not who I am.” How familiar is the idea of denying one’s identity, of being on the down-low? Is “drug dealer” his “secret identity,” or is that the hero he truly is?

Much of this requires forays into magical realism, especially a ring (Dylan’s mom’s wedding ring), which seems to imbue the duo with dynamic abilities. Does it really empower them, or does it merely serve as a metaphor — one ring to unite them, to rule them all?

Such heady stuff might be interminable if not for the joyous music, which elegantly toggles between doo-wop, hip-hop, pop, R&B and good ol’ showtunes. Try walking out after the finale, “Middle Spaces,” and not humming along for an hour.

The performances are stellar, from Breckenridge’s clarion voice in the smallish role of the mother (she’s underused, but memorable) to Christopher (charismatic in several roles) to Broadway legend Andre De Shields, conjuring James Brown with his light-footed, bracing turn as Mingus’ granddad, a Bible-verse-spewing pedophile. Indeed, there are no weak spots, vocally or otherwise.

Beltran has the more thankless part in Mingus, the character who inspires the narrator but whose inner life we can only speculate about, though he’s powerful in it. Chanler-Berat, though, holds it all together as the protagonist who can never quite get away from his past.

As a world premiere, there are still issues to work through; the first act is too long, though cutting it too much might necessitate losing some great numbers (the longish opening number is a hoot); and the ending isn’t quite there yet. But its insights into race, into sex, into friendship and music and parent-child relationships and … well, it takes on a lot, and does so superbly. I want to see it again.

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition March 21, 2014.