Memoir of Giffords’ gay staffer light on insights, interest

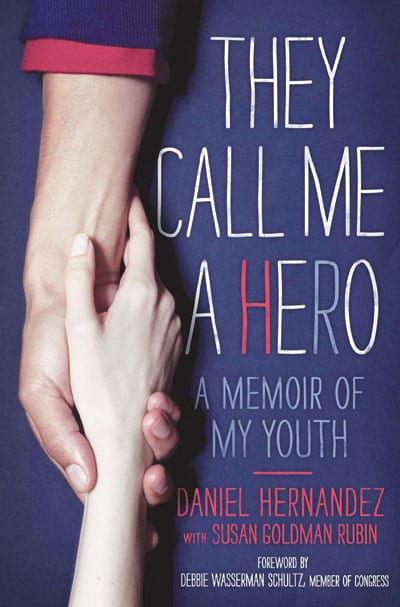

They Call Me a Hero: A Memoir of My Youth by Daniel Hernandez with Susan Goldman Rubin (Simon & Schuster 2013). $18; 224 pp.

They Call Me a Hero: A Memoir of My Youth by Daniel Hernandez with Susan Goldman Rubin (Simon & Schuster 2013). $18; 224 pp.

These days, it takes more than a cool costume to be considered a hero. But in his recounting of his role in a prominent shooting, Daniel Hernandez says there was nothing heroic about his actions.

Many would disagree. The event on January 8, 2011, was supposed to be fun and informative. Congresswoman Gabrielle Gifford, who loved interacting with her constituents, had planned a meet-and-greet on that Saturday afternoon in Tucson. Hernandez, the gay 20-year-old intern in Gifford’s office, was there to help register attendees and to do light crowd control.

Everything was going well … until he heard explosions and one word: “Gun!”

Almost automatically, Hernandez headed for the stage, with Gifford first on his mind. With barely a pause, he pressed his hand against her wound to slow the bleeding, an action that may have saved her life. He comforted her, and rode with her in the ambulance to the hospital.

Years before, as a child, Hernandez had wanted to be a doctor. He was a good student in school and was teased for his bookishness and for being gay. Undaunted, he stayed true to himself and sought classes and training for a future medical career.

He blames his obsession with politics on Hillary Clinton. He became fascinated by her run for the White House and volunteered to work for her campaign, a love that extended to his college years, the friends he sought and, later, to a desire to serve others in a political career that also allowed him to do motivational speaking.

On that winter day two years ago, though, Hernandez was just an intern. His future, he hoped, would be spent serving others through volunteering. But he was destined to become a hero first.

There are a lot of bumps in They Call Me a Hero, starting with its subtitle (A Memoir of My Youth). Hernandez (with Susan Goldman Rubin) doesn’t actually include a whole lot about Hernandez’s youth; instead, the vast majority of this memoir is about that day in Tucson, the whirlwind of media attention afterward and Hernandez’s subsequent political activities.

There’s also an awful lot of back-patting.

To the good, however, this book may loudly urge teens to give of themselves to better their world. With an overwhelming record of achievements, Hernandez is a tornado of service to others and he makes volunteerism seem fun, almost like a community in itself. That may spur young readers to mobilize.

Indeed, the intended audience for this book is 12-to-18-year-olds but there’s certainly no reason adults can’t read it. If you can look beyond the awkwardness and boasting here, you may find a hunk of inspiration, too.

— Terri Schlichenmeyer

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition September 13, 2013.