Worship takes different forms in ‘Hedwig & the Angry Inch’ and ‘The Christians’

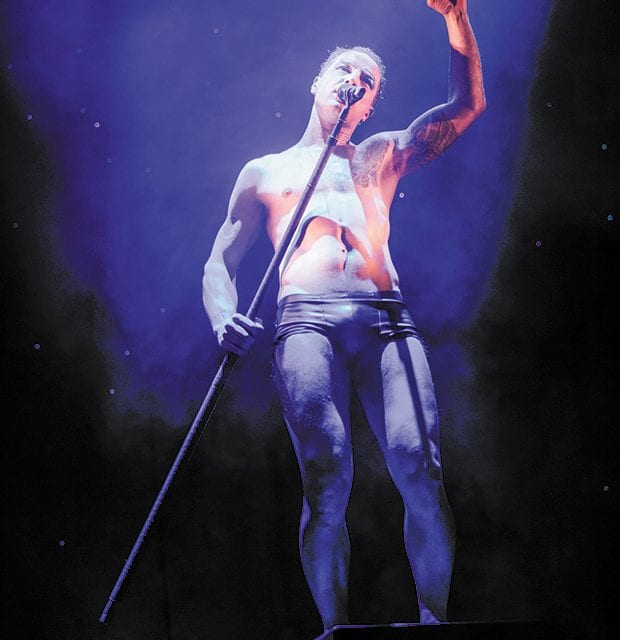

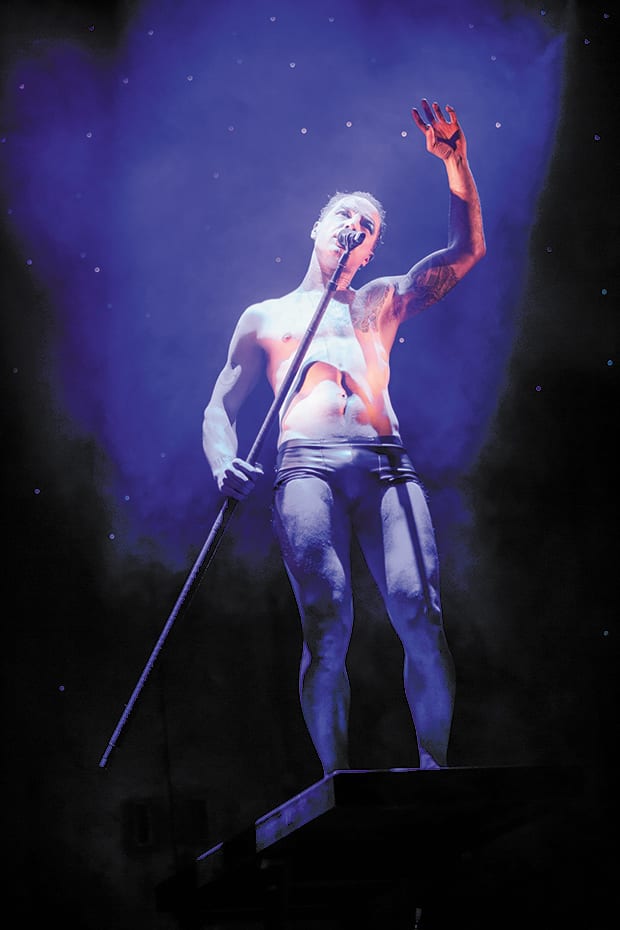

PSALM WONDERFUL | Euan Morton, above, sings about a ‘Wicked Little Town’ … from Dallas! Below, Chamblee Ferguson kneels for inspiration in ‘The Christians.’

Brother and sisters, please be seated. You’re gonna be taken to church.

Brother and sisters, please be seated. You’re gonna be taken to church.Which church is up to you. Maybe the suburban megachurch on the brink of schism as in The Christians. Or perhaps you prefer to worship on the altar of rock-n-roll. Hedwig & the Angry Inch has you covered there as well. Both will take you about 90 minutes — and you don’t even have to go on Sunday.

You’ll probably recognize the church of The Christians as the more conventional. The set is of that modern kind, with a choir standing behind a brightly-lit podium and a stage dotted with microphones. The pastor Paul (Chamblee Ferguson) begins his homily with good news: The mortgage on their 3,000-seat cathedral has just been paid off. But now some more somber information: Paul has come to realize that the dogma he has been preaching for decades might be… well… off. Maybe the Bible doesn’t require you to believe in Jesus; maybe Jesus saved everyone because he believes in you. And therefore, there is no hell. Ahem.

The sermon doesn’t sit comfortably with everyone in the church. Certainly not the associate pastor, Joshua (Steven Michael Walters), who feels betrayed by this sudden about-face. And if Paul felt so strongly about this for so long, why did he wait until donations had set the church up financially to bring it up, and not sooner?

What’s really going on, here?

These are heady, relevant questions that playwright Lucas Hnath raises — ones I wish were raised more often, and at actual congregations across America. Is religion exclusionary, or inclusionary? Can even the word of God have more than one meaning?

These are heady, relevant questions that playwright Lucas Hnath raises — ones I wish were raised more often, and at actual congregations across America. Is religion exclusionary, or inclusionary? Can even the word of God have more than one meaning?Hnath employs a lot of familiar Christian imagery, especially during the controversial sermon that dominates the first third of the play. You can imagine Pastor Paul’s words ringing true to the ears of many progressive churches as he parses the gospels and challenges his flock. But as might ring too-true in the current cultural climax, the refrain “don’t be intolerant of intolerance” grabs hold of some parishioners — “I don’t want to think differently,” one insists as the idea of learning a new path.

The style usually works. There’s very little actual action — characters stand or sit and speak to each other through microphones, even when the setting is clearly meant to be more intimate. The apparent intent — to make this seem like a real discussion of beliefs during an actual service — is often distancing and doesn’t quite work. But what does work are the impassioned performances. Ferguson’s humanity as a preacher gripped by a desire to do right, though the heavens fall, is achingly real. Walters never comes off as an object of derision but as a genuinely confused believer. We wait almost until the end to hear Christiana Clark, as Paul’s wife, speak one word, but when she does, it thunders.

The Christians is provocative, but it doesn’t provoke for its own sake. You can feel the audience working out their confusion and doubt along with the characters onstage. Then again, without doubt, what good is faith anyway?

The Church of Hedwig is of a very different kind of religion entirely — more of a cult, really. (As in The Christians, though, most of the characters communicate through hand-held microphones.) Hedwig (Euan Morton) started life as an East German gay boy who fell in love with a Westerner; then underwent a botched gender-reassignment surgery (leaving her with the eponymous Angry Inch); finally wrote songs for an American wannabe musician, Tommy Gnosis, turning him into a superstar … only to be dumped for being “off message.” My brethren, Hedwig has an axe to grind … and we don’t mean a Stratocaster.

Don’t try to wrap your mind around the plot of Hedwig & the Angry Inch, one of the purest musical characters devised in the latter half of the 20th century (it’s my generation’s Rocky Horror). Her particulars are fascinating, but her struggle is real. And you can feel it in John Cameron Mitchell’s witty script and composer Steven Trask’s kick-ass songs. The musical has been a showcase for a strong leading actor for nearly two decades (Uptown Players did a wonderful production 18 months ago), but this version, imported from Broadway, has its own energy.

Morton doesn’t so much flirt with the audience, or even seduce them, but rather date-rape us with his thrusting pelvis face-humping front-row denizens, obsession with fellatio single entendres and improvisations of great lines, many targeted locally (among them jokes about Cassie Nova and pulled pork barbecue, but also Melania Trump).

With moves like Jagger and shoes like Elton, Morton’s charisma is mirrored by the canny underplaying of Hannah Corneau as Hedwig’s Croatian husband Yitzhak. Hedwig abuses and humiliates him, which makes Corneau’s emergence as a swan so satisfying. The entire ending — a painfully raw but hopeful moment of self-acceptance — is an anthem of empowerment, and an exquisite, tearful victory for all misfits. Can I get an amen?

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition February, 10 2017.