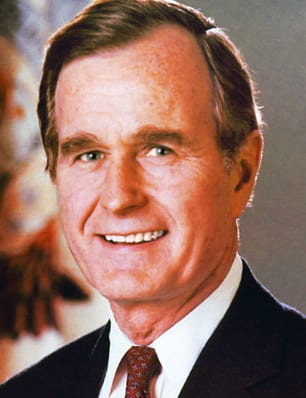

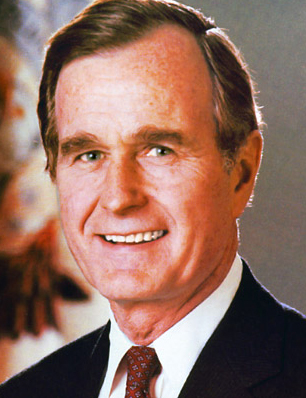

President George H.W. Bush remains in guarded condition in the intensive care unit of a Houston hospital, according to the Houston Chronicle.

His prognosis is unclear, but now seems like a good time to look back on Bush 41’s legacy on LGBT and HIV/AIDS issues.

Bush came into office on Jan. 20, 1989 promising a “kinder, gentler nation.” That was wonderful news to the gay community that had been ravaged by AIDS. During the previous eight years, the nation had been led by a president who had uttered the word AIDS for the first time just a little more than a year before.

Locally, gay-rights advocates were focused on things like police stings at Reverchon Park and employment discrimination, but Bruce Monroe, who was president of the Dallas Gay and Lesbian Alliance in the early 90s, said national LGBT groups were primarily focused on HIV/AIDS.

When Bush took office, “don’t ask, don’t tell” and the Defense of Marriage Act were still an entire administration away. At that time, service members who were found to be gay or lesbian were court-martialed, imprisoned and given dishonorable discharges. And the concept of marriage equality was still several years away.

AIDS was the major concern of the community — gay men were getting it and lesbians were taking care of their friends.

In 1990, Bush’s Secretary of Health and Human Services, Louis Sullivan, attended the International AIDS conference in San Francisco. His keynote address was drowned out by activists from ACT UP. Many delegates walked out.

Bush had been invited to speak, but he declined. In 1987, as vice president, he attended the conference in Washington, D.C. and was roundly booed, so the community understood his reluctance to attend. But what offended people in the LGBT community at the time wasn’t sending a proxy to the event, but that Bush attended a fundraiser for anti-gay Sen. Jesse Helms that night instead.

In 1991, more protests against the president and his handling of AIDS were held. In September, Bush defended his administration’s handling of the epidemic and said in a news conference, “Here’s a disease where you can control its spread by your own personal behavior.”

But spending on research had grown to $4 billion annually. While AZT was still the only drug prescribed for people living with AIDS, scientists were closing in on medications that would make the disease manageable within the decade. And Bush responded to demonstrators saying that he got the message on the need for compassion “loud and clear.”

In 1991, Social Security expanded its rules to allow people with AIDS to go on disability and claim benefits. At the same time, a Helms-sponsored bill signed into law by Bush prevented people with HIV from entering the country.

In August 1992, DGLA organized a protest against Bush when he addressed a conservative religious group at the Dallas Convention Center.

“Republicans were embracing religious groups and eliminating the division between church and state,” Monroe said.

Responding to the president’s “family values” campaign theme, Sandy Moore, organizer of the newly formed Dallas PFLAG chapter, said at the rally, “George and Barbara Bush have not cornered the market on standing up for their children.”

Some demonstrators laid on the plaza outside the hall while others chalked their outlines and wrote the names of friends who had died of AIDS. The idea was that attendees to the religious conference would have to walk over the chalked bodies and see names of the dead.

But frustration grew during the quiet candlelight protest. After more than an hour of speeches and chanting, demonstrators moved from the plaza to the glass entrances of the convention center (then a much smaller venue) and began pounding on the doors hoping the president and his donors would hear the noise.

“Four more months,” the protesters chanted as they pounded on the convention center glass.

Mounted Dallas police locked doors to the building and dispersed the crowd. One protester, William Daniels, refused to leave and was arrested.

At the Republican convention held that month in Houston, Mary Fisher, a mother with AIDS who was a lifelong Republican, told the delegates “AIDS doesn’t discriminate.”

But hers was closely followed by a caustic speech by Patrick Buchanan, who called Hillary Clinton a radical feminist and accused Clinton of supporting abortion on demand and gay rights.

Monroe said he believes that speech sealed Bush’s legacy in the minds of most people in the LGBT community.

“Bush was an intellectual man,” Monroe said. “He had mouthpieces in the Republican Party say things so he didn’t have to.”

Monroe said Bush’s legacy on LGBT rights was insignificant. Some gains were made especially on the local level. In Dallas, DGLA won the Mica England case against the Dallas Police Department that forced the city to stop asking sexual orientation on its employment application and using it to disqualify candidates.

He said that nationally, advances were made for people with AIDS. More money was spent on research than under Reagan, but Monroe said that only happened when the fear grew that HIV was spreading beyond gay men.

But he said the Red Ribbon around the White House during Bush’s term was an indication that for the first time there was a president who had some understanding of the threat of AIDS.