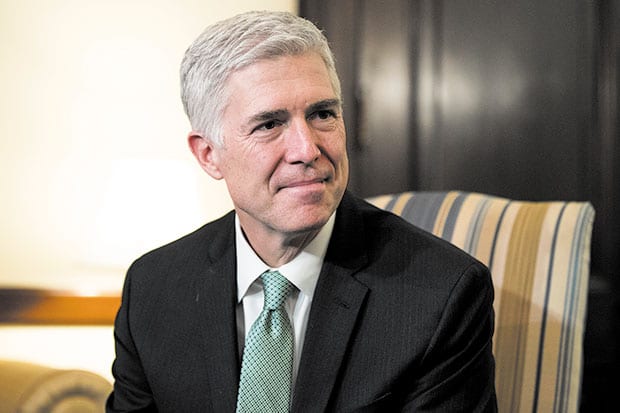

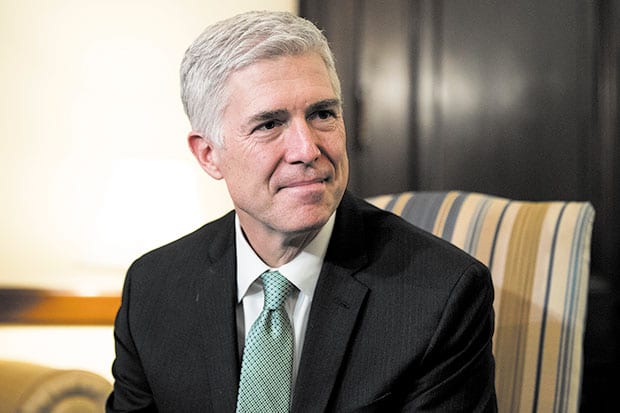

LGBT advocates worry that SCOTUS nominee Gorsuch will fall on the wrong side of that line

Lisa Keen | Keen News Service

lisakeen@mac.com

The big question for the LGBT community over the next week is not so much whether President Trump’s nominee for the U.S. Supreme Court will be confirmed; he almost certainly will be. And almost every national LGBT group opposes his confirmation.

The real question is if Judge Neil Gorsuch will discuss, during his March 20 confirmation hearing, whether he will favor the U.S. Constitution’s guarantee of free exercise of religion over its guarantee of equal protection of the law.

Most people in the LGBT community supports both rights, and most judges will say they do, too.

But the increasingly frequent clashes between those who support equal rights for LGBT citizens and those who feel fear or hostility toward LGBT people is coming to a head at the U.S. Supreme Court. And the legal battleground of those clashes is equal protection versus free exercise.

Neil Gorsuch’s confirmation is virtually guaranteed. As Democratic U.S. Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand pointed out recently, the Republican majority in the Senate — the GOP holds 32 seats there — will almost certainly change the Senate rules, if necessary, to ensure Gorsuch is confirmed by a simple majority vote.

And as for the religion-versus-equal protection balance, Gorsuch’s record lends itself to the assumption that he will weigh religious arguments more heavily than those of equal protection. If asked about a specific case on LGBT cases, he’s likely to say — as most judicial nominees do — that he will abide by the Supreme Court’s decisions on those cases.

But the Supreme Court’s decisions have been mixed. Pro-LGBT legal activists have won several major victories at the nation’s highest court in recent years, seeing the ban on marriage for same-sex couples (Obergefell v. Hodges, 2015) and the Defense of Marriage Act, which prevented equal federal benefits for same-sex married couples (U.S. v. Windsor, 2013), struck down by SCOTUS.

But anti-LGBT activists using religious exercise arguments have scored points, too. The Supreme Court’s Hobby Lobby decision in 2014 was seen as a “dangerous and radical” one that could enable employers to simply claim religious beliefs to gain exemption from laws barring discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity.

In its analysis of Gorsuch’s record, Lambda Legal officials concluded that this nominee has displayed “a vision of a society where religion prevails over law, and where the concerns of religious parties override the concerns of other citizens.

“In supporting this vision, Judge Gorsuch’s opinions open the door to all manner of assaults on the civil rights of ordinary citizens — including lesbians, gay men, bisexuals, and transgender people, and everybody living with HIV,” Lambda officials said in a statement.

Gorsuch’s record, according to that statement, is “more recklessly conservative” than that of Justice Antonin Scalia, the person he was nominated to replace.

That is a particularly bold statement. Before he died in February 2016, Scalia had amassed the worst voting record on LGBT issues of any justice on the high court. Some court observers believe that Gorsuch can’t do worse than Scalia, so his confirmation will simply put things back to the way they were.

But Lambda disagrees.

“Don’t for a second think that, because Gorsuch would be replacing Scalia, he’d be no more than a continuation of the status quo. It’s far worse than that,” Lambda officials opined in an email to its supporters last month, marking the first time Lambda Legal has publicly opposed a Supreme Court nominee.

Other LGBT organizations are also opposing Gorsuch.

The National Center for Lesbian Rights said Gorsuch has a “dangerously radical view of religious liberty that would undermine anti-discrimination protections for LGBT people and others.”

GLBTQ Legal Advocates & Defenders (GLAD) said he has “expressed hostility to progressive movements’ use of the judicial process to safeguard constitutional liberties and protections for all.”

Part of Gorsuch’s record before becoming a judge on the Tenth Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals appears to show a dismissive attitude toward lawsuits seeking equal protection for LGBT people. In a 2005 article he wrote for National Review Online, he referred to such lawsuits as part of a “social agenda” and suggested that, rather than the courts, progressive people should seek redress from “elected leaders and the ballot box.”

His other pre-court writings revealed his ability to parse language to suit his needs. For instance, as an editor of The Federalist Paper at Columbia University, he objected to a description of the paper as a “political organization.” Instead, he and his fellow editors explained, it was a “forum” for debate on “the issues of the day.”

As a judge on the Tenth Circuit, Gorsuch wrote a concurring opinion in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby that suggested employers would be “involved in the wrongdoing of others” if they complied with employment laws that prohibited certain types of discrimination in health care coverage.

The case dealt with a department store employer who objected to paying for contraception for the company’s employees. Advocates in the LGBT community, however, easily envision employers making religious objections to things like preventive care against HIV infection or the use of medical insemination for lesbians seeking to have children.

What the LGBT community has to hope for is that Gorsuch’s preference for freedom of religion can be tempered by his apparent comfort with LGBT people on an individual basis. A New York Times article noted that Gorsuch has had two openly gay clerks, at least one of who told Gorsuch he was gay before Gorsuch hired him.

In addition, the judge belongs to a church in Boulder, Colo., that welcomes gays. And, to the extent this might be telling, one gay male friend said Gorsuch “didn’t skip a beat” when he told Gorsuch he was gay. In fact, said the friend, Gorsuch and his wife have been very welcoming of the man and his husband.

At a law forum in Columbus, Ohio, on Feb. 24, a gay man who had been one of several housemates of Gorsuch at Harvard Law said he felt Gorsuch was comfortable with him and two other housemates who were gay.

But having a gay law clerk or friend has not always translated into a belief that LGBT people should have equal protection under the law. Several years ago, another New York Times article noted that Justice Clarence Thomas, who has consistently voted against LGBT people in cases before the court, was very accepting of his openly gay clerk.

Gorsuch himself clerked for Justice Byron White seven years after White wrote the 1986 decision in Bowers v. Hardwick that held that any right to privacy in the federal constitution did not extend to private sexual relations between same-sex partners. In a speech honoring White, Gorsuch said he admired White “enormously.”

White, said Gorsuch at the 2006 opening of an exhibit about the former justice, “passionately believed in human equality: the dignity of all persons and civil rights.”

The Hardwick decision was reversed in 2003 in a decision led by Justice Anthony Kennedy, for whom Gorsuch also clerked briefly during the 1993-94 session after White retired.

Senate President Mitch McConnell said the Senate would likely vote on Gorsuch’s nomination the week before its April 8 recess.

© 2017 Keen News Service. All rights reserved.

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition March 17, 2017.