A 22-year-old DACA recipient contemplates being deported from the country where his great-grandparents and most of his relatives are citizens

DAVID TAFFET | Senior Staff Writer

taffet@dallasvoice.com

Francisco Rojero’s great-grandparents are American citizens. He’s not. But he took advantage of DACA — Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals to stay in this country.

Rojero, 22, is a full-time student at Collin College in Plano, taking more than a full load of classes, and he works 30 hours a week at the Angelika Film Center at Mockingbird Station. When President Donald Trump announced an end to DACA, Rojero said he was heartbroken.

He said more than 90 percent of his family members are U.S. citizens. His great-grandparents became citizens in 1986 through an amnesty granted during the Reagan administration. His grandmother was in the process of receiving her citizenship when she died suddenly of a heart attack at the age of 40, leaving her younger children without green cards.

For years, Rojero’s parents traveled freely between the U.S. and Mexico. “Before Sept. 11 (2001), it was easy to travel back and forth,” he said.

Then, 12 years ago, his parents decided to move to Littlefield, 35 miles northwest of Lubbock, where they had relatives. Rojero was 10.

“My parents didn’t look for ways to legalize themselves,” Rojero said.

For that final move to this country, his parents hired a white couple to drive the three children across the border in the family car. He said he thinks the couple gave the kids a sedative so they’d be sleeping as they crossed into the U.S., but he remembers forcing himself to stay awake to care for his younger brother and sister, who were 3 and 5 at the time.

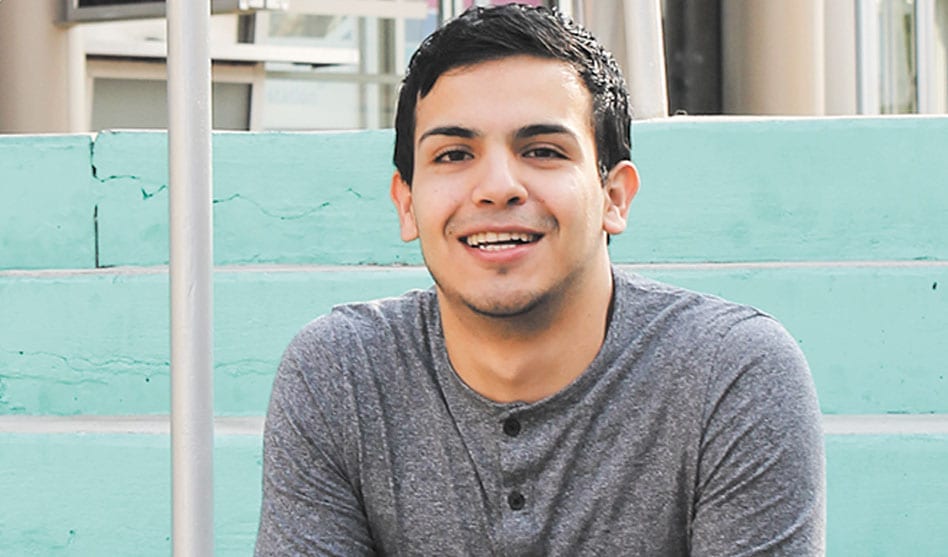

DACA recipient Francisco Rojero sits on the steps of the Angelica Theater where he works. (David Taffet/Dallas Voice)

His mother walked for 48 hours to meet them on the American side.

Rojero vaguely remembers the town of Sombrerete, in the north central Mexican state of Zacatecas, where he was born. But his brother and sister have no memory of life in Mexico. And though he still speaks Spanish fluently, Rojero recently tested for a translation job and scored higher in English than Spanish.

After living in Littlefield for about six months, the family moved to San Jose, Calif., but then returned to Texas seven years ago because there were more job opportunities here. Rojero’s father works in construction and is steadily employed, especially in the wake of Hurricane Harvey, since there will likely be more need for construction workers than there are construction workers.

His mother works temporary jobs in the fields or in restaurants.

Rojero always excelled in school and was always top of his class. When the family moved to California, he was in a Spanish-English program for two years. Once he learned English, though, he wasn’t learning much else.

So he spoke to a counselor and tested out of the program and again began to stand out once more. Although he was among the best students, he knew he was at a disadvantage.

“I kept nagging my parents,” he said. “I wasn’t going to be able to go to college like the other kids.”

Then, when he was a junior in high school, President Barack Obama issued an executive order establishing DACA. And, Rojero said, “My life changed dramatically.”

DACA meant he was able to get a driver’s license, go to college and get a job.

Rojero was among the original group that signed up for the program, and he helped friends who were having trouble with the application enroll. His sister has registered as well, but his brother, now 15, isn’t old enough to participate in the program.

When Rojero was 18, he moved out on his own and began working. “I’ve always been independent,” he said.

He said when Trump was elected, he was working in Plano. The morning after the election, he walked out of his office crying and met a Muslim woman, an aviation engineer in a neighboring office, sitting on the curb crying as well. That’s when he decided he needed to get as much education as possible and enrolled in college.

Now, he said, with DACA scheduled to end, he faces deportation. He said he sees Trump’s move to end DACA as the act of a bully, and bullying the most helpless is something tyrants and dictators do to maintain power, not something an elected official in the world’s greatest democracy does.

“It feels like being rejected from your own country,” he said. “I’m a patriotic American. I have American values. I wish he [Trump] would sit down across from me so I could tell him why he’s wrong.”

Rojero called coming out as undocumented a “second coming out.” In school, he said, teachers would talk about “illegal immigrants,” not knowing his immigration status. There was stigma attached to it.

Congress is considering the DREAM (Development, Relief and Education for Alien Minors) Act, which was first introduced in 2001. It would provide relief similar to DACA. Rojero isn’t confident it will pass this year.

If he’s threatened with deportation, he said, he’ll leave the country. But he has no intention of moving to Mexico. He’s already looked into immigration to Canada, and knows that he qualifies with his education. He said he doesn’t mind the cold weather and likes that Toronto is such a diverse city.

Although he can’t vote, he said, six of his friends did, at his urging. One friend, however, didn’t vote, And Rojero said he’s glad she didn’t: “My best friend’s a Republican,” he said. “She might not understand until I’m not here.”

He said his friends have been very supportive of him as his future hangs in limbo, and some even offered to marry him to get him his citizenship. But Rojero’s having none of that: “I don’t feel I should do that to prove I’m American.”

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition September 15, 2017.