4 legendary performers come together for an Outrageous Oral program honoring the legacy of drag in Dallas

Tammye Nash | Managing Editor

Tammye Nash | Managing Editor

Gay Dallas has always been known as a drag mecca — the land of legends like Lady Shawn, Tasha Kohl, Diva Sanchez, Rikki Rousseau and, of course, Kandi Delight. Those are names from way back in the day, when The Landing down on Pearl Street boasted a grand stage with curtains and a runway where you could see, not just a drag show, but a full-fledged drag extravaganza every week.

They had well-rehearsed group numbers and a trio of back-up dancers and special guests in from out of town, like Naomi Sims. Drag shows at The Landing were professional productions, that live on today in the likes of The Rose Room at S4. You can’t tell the history of LGBT Dallas without talking about drag.

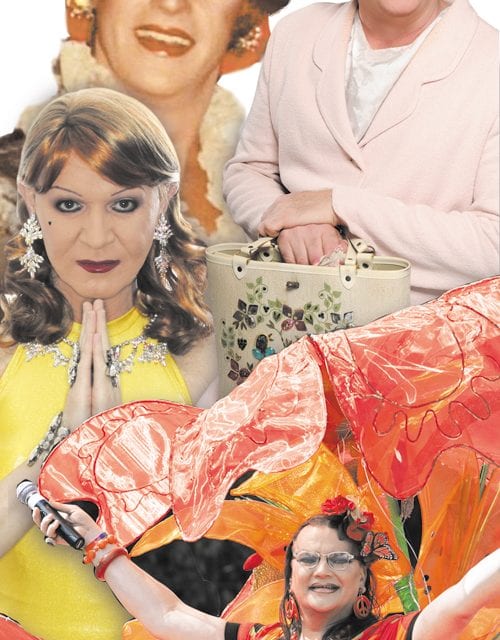

That’s why the May installment of The Dallas Way’s Outrageous Oral program presents “One Night Only: Four Legendary Performers Telling Outrageous Stories.” The special program features Michael Lee (Michael Doughman), Sister Helen Holy (Paul J. Williams), Edna Jean Robinson (Richard Curtin) and Pattie Le Plae Safe (Rodd Gray) on stage together for the first time ever.

The days of The Landing and other such venues were a time, recalls Doughman, when drag was primarily a source of entertainment, and a very popular one at that. He points to The OP and the Wooden Nickel and later The Rose Room as evidence that the presence of drag has “remained pretty constant and sustained a very high quality of performance” through the years in Dallas.

But by the mid-1980s, the specter of AIDS had begin to cast its pall over North Texas, and the nature of drag in Dallas began to change.

“When AIDS started to really become an issue here, drag shows became a way to fight back,” said Doughman, now executive director of Dallas Tavern Guild, adding that his first time in drag was in 1984, to raise money for TGRA. “Drag shows became a way to raise money to take care of our own, and a way to just forget about your troubles for an hour or two and laugh and have a good time again.”

But, Doughman notes, “it wasn’t the pretty girls, really, not the glamour drag” there on the front lines. Instead it was the ordinary guys with day jobs as bankers and waiters and whatever else who threw on a dress and painted their faces for the cause when the government wasn’t funding agencies or programs or services for those in the midst of the epidemic.

“That’s when it started, the mantra of charity drag,” Doughman said. “Other than shows at places like the OP and The Wooden Nickel where they had regular casts and big productions, every other show around was there to raise money for some organization that was trying to get started to help people. Sometimes the shows were more specific; we were trying to raise money to help somebody pay their rent or to bury them when they died and their family had abandoned them.

“Not everybody had a lot of money, and couldn’t do anything else to help. But just about everybody could pay a $2 cover and then throw some tips in a jar to help out. Whenever the need arises, we’ve always been able to get a bunch of people in drag and raise a chunk of cash to support a cause.”

Mostly, as Doughman said, the “pretty girls” — aka “the pageant girls” — were the ones making a living doing drag, while the “charity girls” focused on raising money, mainly for AIDS. For the charity girls, he said, “you didn’t have to look good. You didn’t even have to have talent. You just had to be able to help people forget their troubles for a little while and raise money to help those who needed it. You just had to make people laugh and give you money.”

And for the most part, there remained a huge gap between the pageant girls and the charity girls. Then along came Patti Le Plae Safe — Rodd Gray in daily life — who managed to bridge the gap.

Gray said he was busy being an AIDS activist, and never had any intention of getting into drag — until the day that Bill Nelson and Terry Tebedo talked him into donning a dress and make up for an AIDS fundraising event. Friends raided their closets to get him dressed up and made up, and then when he performed, “Tom Davis gave me a $20 tip! I was not supposed to be a drag queen, but my friends talked me into it, and I made money doing it. And I couldn’t deny the money was needed.”

“Patti” soon became quite popular on the drag fundraiser circuit, and one day, on a dare, Gray decided to enter a pageant. That first time almost became the last time thanks to a less-than-supportive pageant queen.

“She told me, Patti, you’re not pretty. You’re not talented. You need to go on and do your charity shows and leave the pageant stuff to us,” Gray recalled. “I went home and I cried.”

But instead of letting the petty insults derail his efforts, Gray decided, with the encouragement and help of his good friend John Gordon, to prove that it was possible to walk successfully in both sides of the drag world. And on Patti’s first trip to the Miss Gay America Pageant, she won first runner-up, trading that sash for the winner’s crown a few short months later when winner Ramona Leger died.

Gray, a hair stylist who owns his own shop, as Patti has helped bring the two sides of drag together in Dallas, earning the respect and admiration of the pageant girls, while earning hundreds of thousands of dollars for charity. “I’ve been doing this for 29 years now, 29 gloriously wonderful years,” Gray said. “It’s all about helping my community. That’s what drag is, for me, and for so many others.”

Richard Curtin, active in the community for about 27 years, is another “charity girl” who says, “Some of most important work I did in drag [as Edna Jean Robinson]. My specialty has always been fundraising.

“For a decade, I begged and borrowed and stole — no, I never stole anything — any thing I could get to give away or auction off or use as an incentive to get people to buy raffle tickets. So steadfast, for a decade, to make sure we raised the money people needed,” says Curtin, who in recent months has transitioned from drag performer to businessman as owner of Zipperz.

And even though those years were filled with hardship and heartache as the AIDS epidemic continued to ravage the community, the struggle also serve to “tighten the bonds of our community, to tighten our sense of being a family,” Curtin said. “Through those years, for so many of us, our family was the bar. We worked there, or we played there or we organized there or we raised money there. It was our family.”

But turning his gaze from the past to the present, Curtin continued, “I think a little of that is missing now. A lot of that sense of community, of family, is missing now because the community is different. Is that bad? Is it good? I think it’s just called evolution. The world has changed, and our community has changed. It’s just a new world now.”

While HIV/AIDS remains a shadow over the LGBT community, the immediacy of the epidemic has faded a bit, especially for the younger men and women who never lived in a world without the HIV medications that are adding quantity and quality to the lives of those with the virus. AIDS is no longer the death sentence it once was, but instead a manageable chronic illness.

Still, Curtin said, “Those of us who made it through the crisis, who lived those years when we lost so many so fast — we remember that. And we have to pass it on. That’s what this Dallas Way is about, I think. We remember, and by talking about it, we can teach the younger people about it. We learned by living it. Hopefully we can teach them by talking rather than them having to live it all over again.”

The Dallas Way and its Outrageous Oral programs “celebrate the past,” Curtin said, keeping alive the stories of those who came before and helped build the foundation for this brave new world where LGBT people are claiming equality on an ever-broadening basis. Even marriage equality, he pointed out, is just around the corner.

“We have to celebrate the past, remember it and teach the younger people what it was like, but we have to move forward to the future, too,” he said. “What does this new world look like? It doesn’t look like death. We know what death looks like; we held hands with it, lived with it.

“This, though — this looks like the future, and it looks good,” Curtin declared. “There’s so much to look forward to, and it’s time to embrace the future and walk right on into it. There’s room for all of us, and in the future, there will be even more room for even more of us.”

…………………..

The legends speak

The Dallas Way presents a special Outrageous Oral program, “One Night Only: Four Legendary Performers Tell Outrageproof Stories,” Thursday, May 21, at The Rose Room at S4, 3911 Cedar Springs Road.

Dallas drag icons Michael Lee (Michael Doughman), Sister Helen Holy (Paul J. Williams), Edna Jean Robinson (Richard Curtin) and Patti Le Plae Safe (Rodd Gray), all on stage together for the first time ever, tell stories about their history.

Doors open at 6 p.m., and the curtain goes up at 7 p.m. Reserved seating tickets are $35 each or $50 for two. Standing-room-only tickets are $20. For tickets or sponsorship opportunities call 505-400-4405.

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition May 15, 2015.