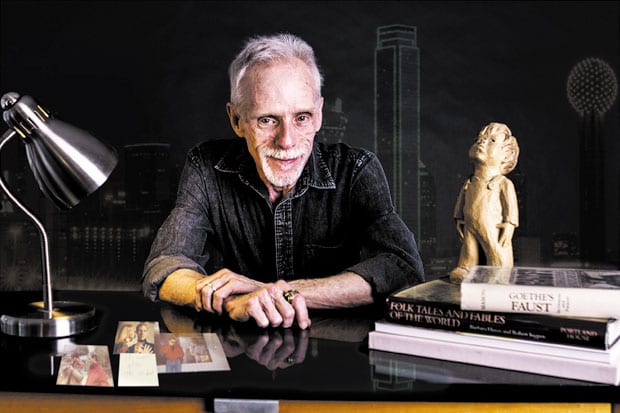

An abduction. An assault. And a 30-year struggle to understand what happened. Behind Terry Vandivort’s eerie one-man show ‘The Incident’

ARNOLD WAYNE JONES | Executive Editor

“Once there was a boy… and something terrible happened to him,” begins — and ends — Terry Vandivort’s one-man show The Incident, and right from the start he draws you in. This is a ghost story, a horror show, a mystery, a confessional … and most remarkably of all, it’s true.

“Once there was a boy… and something terrible happened to him,” begins — and ends — Terry Vandivort’s one-man show The Incident, and right from the start he draws you in. This is a ghost story, a horror show, a mystery, a confessional … and most remarkably of all, it’s true.

Vandivort — who for decades has been one of North Texas’ most reliable and engaging stage actors — plays perhaps his most challenging character ever in The Incident: Himself.

It starts on a frigid November night in 1979. Gay liberation is at its peak, and the AIDS crisis doesn’t yet exist. Sex is fun, free, frequent, but for Vandivort never “casual.” He’s serious about it. Serious about cruising, about his tastes in men (black guys to the front of the line!… and apparently there was a line). Young twink Terry thinks he’s hooking up with a young, nameless stud he meets in a long-since-gone gay bookstore, but instead is abducted, terrorized, assaulted and, obviously, survives.

But that’s just the first act; the second is about his 30-year obsession to figure out exactly what happened.

Originally, Vandivort didn’t actually write this for an audience — he wrote it more as an exercise of exploring a part of his personal history.

“I started writing it after I had six coronary bypasses — it felt like unfinished business,” he says. “In my brain, it was a play, but one that would never be produced because of the graphic nature of both the sex and the violence.”

While the violence conveyed in The Incident — including sexual assault — is horrifying, what perhaps sets it even more apart from your typical confessional solo-show narrative is the stark, pull-away-the-curtain frankness about what being a gay man during the 1970s was really like.

“Gay people have gained a lot of acceptance [in mainstream society] in terms of marriage equality [and the like], but this show is not playing into that reality, but another reality,” Vandivort says. “It was very important to me that, if I was going to tell this story, it’s really important to tell the truth, come hell or high water. Certainly, I could have not gone into the details, and talked generically about cruising. But this is my life, goddammit, and I’m gonna tell it. I was perfectly prepared for judgment — people thinking, ‘You’re a whore.’ But why can’t we talk about anal sex?” (Nevertheless, “No children, please,” Vandivort cautions potential audiences.)

What The Incident covers, though, is much more than the seedy underbelly of trolling for anonymous sex. The aftermath of that November night has stalked Vandivort for decades.

“I had nightmares for two years after the incident and was thinking about it all the time,” he admits. “Even today, some things can trigger [a recurrent panic]. Any time I see those flimsy steak knives like at Denny’s, I go back there. And I did a lot of drugs and alcohol following it — I could drown the memories, force them to retreat into the background. But [with the advent of] the Internet, my obsession kicked into a higher gear. Every time I Googled [my attacker], there would be more information that I would piece together.”

Because the events depicted occurred in Dallas — even if more than a generation ago — there’s an immediacy to the play, with references to old businesses like the Crews Inn and the geography of the city, including exact areas where Vandivort was physically and mentally terrorized. That resonates for the audience … so how can it feel to be the one reliving it? How, in fact, can Vandivort expose such raw nerves in front of 40 strangers night after night? He credits his director, Cameron Cobb, with steering him through it.

“I was seeing something like a Spaulding Gray [first-person monologue], but it wasn’t feeling exactly right,” Vandivort explains. “Cameron just kept asking me, ‘Who are you? You have to figure that out.’ I initially thought, ‘I’m just me!’ But then I started thinking of it as a role — I am playing me, not being me. Once I made it separate from me, it became a character like any other. It is pretty raw because I’m having to relive my own experiences. On the other hand, if you’re doing Long Day’s Journey Into Night, you need to find analogous experiences to make it live.”

A way it lives is in Vandivort’s often unexpected interjection of humor into otherwise dire circumstances.

“One of the ways I cope is with humor — whether appropriate or inappropriate,” he says. “And if it was unremittingly serious from the beginning, I knew it would wear out its welcome. What thrills me about acting is partnerships, so I was seeking a partner [in the audience]. I wanted the audience to be inside me to see the progression and detail of thought and reaction. So I figured I had to find ways to bring them along with me. If they were just passive observers, it wouldn’t work.”

So far, he says — following two public readings plus the opening night performance earlier this week (it continues, in repertory with another show, through October) — the response has been “overwhelmingly positive,” Vandivort says. “I’ve been acting in this town for 40 years, and I think people have an image of me as a funny second-banana.” This show will certain cast Vandivort in a different light. And he’s OK with that. “I got over my fear. I’m ready for anything. I’m perfectly prepared to have someone walk out in the first act and judge me. I’m 63 now. What do I care? If Eugene O’Neill could drag out all his old ghosts, then I could at least have the courage to tell this truth about me.”

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition October 14, 2016.