‘Bonnie & Clyde’ on a spree; Lulu Ward kills Tennessee

ARNOLD WAYNE JONES | Executive Editor

jones@dallasvoice.com

Should we be concerned that Dallas is best known for a presidential assassin, a ruthless oil baron named Ewing, a pair of Depression-Era gangsters and now the Ebola virus?

Well, J.R. is dead, Bill O’Reilly has killed Kennedy again (and the anniversary is ovuh!) and Ebola probably isn’t the crisis we’re imagining it to be. That leaves Bonnie and Clyde, now adapted for a musical and onstage at WaterTower Theatre, to still haunt our sense of worth.

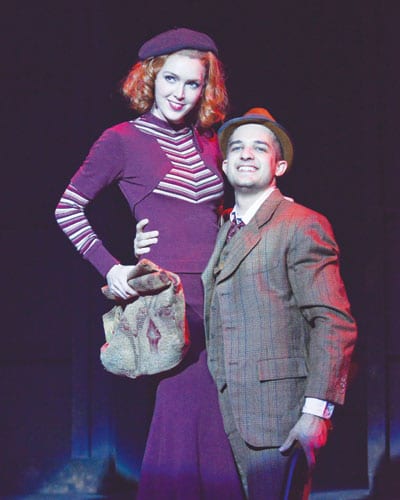

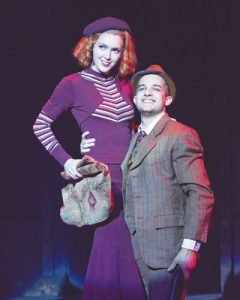

Bonnie (Kayla Carlyle, born to sport a finger wave) and Clyde (John Campione, all smirking testosterone) may have been infamous in part because they were the first to perfect the selfie: Their relentless pursuit of celebrity (including a willingness to sign autographs and pose for pictures during holdups) is part of what made them notorious. But that was also the inherent drama of the relationship — a romance tied to a crime spree: Tristan and Isolde with a fusillade of bullets.

But there’s a folk hero aspect that drives it as well. Cops in the U.S. were corrupt (there’s a hint in Ivan Menchell’s script that they were no better than the Gestapo at the same time), people were poor (banks heartlessly foreclosed on farmers and homeowners — sound familiar?) and Hollywood promoted an image of glamour that intoxicated an impressionable beauty like Bonnie. Why wouldn’t people embrace the brand of B&C, when they were Howard-Beale-ingly “mad as hell and not gonna take it anymore.”

Carlyle and Campione tear up these roles, both portraying deluded dreamers set on a self-destructive path. There’s true sexual chemistry between them, and their voices blow the walls off the roof. Frank Wildhorn’s score is a mix of ragtime, folk, gospel, and old-school country riffs, interspersed with ’80s-style pop ballads; he gets melodically more somber in Act 2, even while the outlaws remain lyrically hopefully. After all, hope was all they had.

The lighting design (by Dan Schoedel) is one of the technical highlights of the production, with also boasts an impressive, expensive set and terrific use of projections — including historical photographs — both by Sarah B. Brown. Indeed, these elements work together effortlessly, with lighting representing gunplay (and bullet-riddled corpses) while the slideshow contributes to the overall sense of nostalgia — a Ken Burns documentary performed live. Director Rene Moreno orchestrates it all beautifully.

The numerous Dallas references make the show that much more enjoyable, and the toe-tapping numbers are performed brightly by the charismatic cast. If they can woo you, no wonder the real criminals got away with murder.

The numerous Dallas references make the show that much more enjoyable, and the toe-tapping numbers are performed brightly by the charismatic cast. If they can woo you, no wonder the real criminals got away with murder.

In the program notes for Tennessee Williams’ Two Character Play, now at the Bath House, director Susan Sargeant acknowledges that the author’s post-1960 output was unpopular with audiences and critics. So why trot out this tortured 1975 chestnut, a meta-play about a theatrical team of brother (Kevin Scott Keating) and sister (Lulu Ward) on a failing tour? Our set is their set, we are their tour audience, but much of it seems to take place out of our sight, though it’s not always sure which is the case. It retreads Williams’ voluble efforts at Southern Gothic extravagance (lots of overblown emotions and purple language). It’s not a good play.

But Lulu Ward is a good — no, a great — actress, and she overcomes nearly every misgiving about the show itself. She’s not given worthy support by Keating, who hams it up (even by Williams’ standards) to an annoying degree, but her intensity as an ageing, drug-addicted, self-deluded and insecure belle is a breathtaking example of a performance elevating the material. It’s a showcase of how to go big without going overboard. Brava!

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition October 17, 2014.