The decades-old tradition of placing poinsettias to remember the singers who died of AIDS will continue at this year’s Chorale performance

David Taffet | Staff Writer

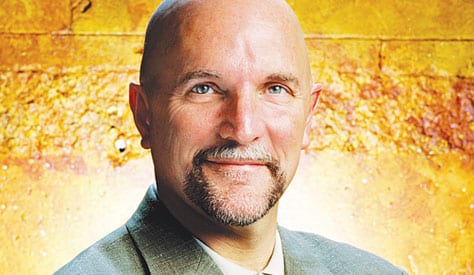

TRIBUTE | Former artistic director Tim Seelig remembers the tradition of poinsettias that began with just one placed on the piano. It has grown to one for each member lost placed on stage. (File photo)

1985. The Turtle Creek Chorale was on its way to becoming one of the foremost men’s choruses in the nation. Its sound, founding member Steve Mitchell said, was “exceptional,” and the audiences were growing as the group’s enchanting name gained recognition.

1985. AIDS hit the chorale.

“It was a surreal time in which we were astonished by the fact that this disease was starting to infect our men and that we were starting to lose them,” Mitchell said. “We were frightened and depressed.”

So, when the first Chorale member became ill, Mitchell didn’t want to believe it.

“My fears became stronger when another member became ill,” he said. “I hoped and prayed it was only temporary and that we would not lose any more.”

But the disease didn’t go away, and the funerals for the members began. Chorale member Robert Emery sang at 120 of them.

“We didn’t have time to cry,” he said. “We’d go from someone’s funeral to someone’s hospital room.”

The disease ravaged the Chorale, but the members closed ranks and used their voices to fight back. Their music was imbued with the emotion that comes only from the ruins of war, which is how the members thought of the AIDS epidemic.

“We had a war mentality,” Emery said, and that attitude helped him cope through the battles that took Chorale members’ lives.

There came a time when the chorus had lost more members than the 120 men who were singing in the Chorale.

Chorale board member Kevin Hodges remembers that time — a time when he sang with a member one week and then sang at his funeral the next week.

“In a sense, that’s how you coped — by singing,” he said.

The music healed the souls of the men who were watching their friends die, and Hodges used it to shore up strength as he sang at the funerals. There were so many funerals that his memories of them are blurry. One of them, though, still echoes in his heart.

John Thomas, the executive director of Resource Center, died, and the Chorale raised their voices in remembrance.

“John Thomas’ funeral felt like you were singing for this icon who had passed away,” Hodges said. “Like you’re out of your own body. This can’t be real.”

Tom Seelig joined the Chorale as artistic director in 1987, and around that time, the tradition of the poinsettias began.

“I do wish I could remember who first thought of a poinsettia,” Seelig said. “I do remember that it began early on with a single poinsettia on the piano in memory of those who had passed.”

When that number reached 20, the tradition evolved into placing one live plant for each person across the front of the stage.

“The number grew,” Seelig said. “At 50, they were crammed across the stage.”

Each year, the performance included “All Is Well” and “Silent Night.”

“It was something they had sung with us,” Emery said.

While the human loss mounted, the Chorale stood strong. Its reputation, like its voice, reverberated throughout Dallas and the country, but people also knew how many members had been lost. Several years into the epidemic, WFAA-TV in Dallas asked to profile the chorus and how it was dealing with AIDS.

“There was quite an uproar among the members,” Seelig said. “Many were not out at work. Others were afraid we would become known as ‘The AIDS Choir,’ and people would make assumptions that 100 percent of the singers were ill.”

However, they decided the risks were worth putting a face to AIDS. Soon after, PBS produced a documentary titled After Goodbye, An AIDS Story about the Chorale’s journey of grief. It won an Emmy Award.

“The chorus never became known as ‘The AIDS Choir,’ but it did become very well known as one of the most important healing and comforting voices in the community, singing at countless memorial services while taking care of the singers who needed it,” Seelig said.

Jamie Rawson, who joined the Chorale in 1994, felt that bond. He remembers when Seelig told the members during a rehearsal that a former singer had died after a long, expensive battle with AIDS. His family didn’t have the $800 to pay for the cremation.

“Tim said, ‘We have to help with this one,’” Rawsom remembers. “We were able to collect $1,300. I’ve never been a member of a church or any group that had that kind of immediate response. I knew right then and there that The Turtle Creek Chorale would remain an important part of my life whatever else I did and wherever else I might find myself.”

Mitchell agrees, and his heart is tethered to the Chorale. He left in 1996 after losing 50 friends to AIDS, but he returned a few years ago.

“After 23 years, I had escaped the infection and saw that people were living with HIV,” he said. “Today, I am home with my beloved chorale.”

The tradition of the poinsettias, still strong, represents so many of Mitchell’s friends who contributed to making the Chorale what it is today. This year, 197 poinsettias will recall members who have died.

“I sing for them,” Mitchell said. “I sing for my present brothers, and I sing for the greatness that will come for generations to come.”

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition December 6, 2013.