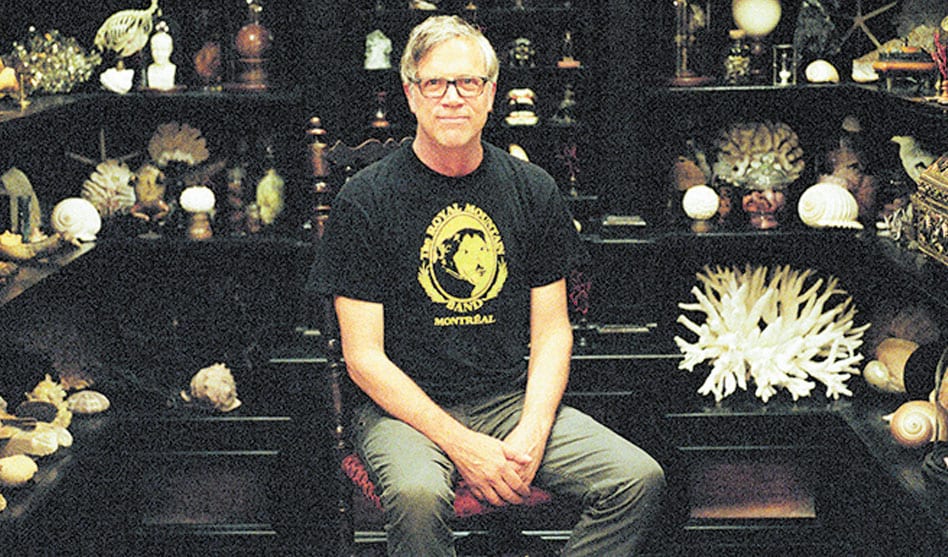

Out director Todd Haynes shares his passion for the past in the magnificent ‘Wonderstruck’

ARNOLD WAYNE JONES | Executive Editor

jones@dallasvoice.com

And for filmmaker Todd Haynes, that’s literally true.

Haynes is one of current cinema’s genuine artists. He thinks and talks about filmmaking with the intelligence and thoughtfulness of a novelist, but his knowledge of film history — and his ability to capture the “look” of different eras — has set him apart from his contemporaries, if not bestowed upon him household-name status.

In fewer than a dozen works — seven feature films, a TV miniseries, plus a handful of released shorts, including his infamous Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story (told with a cast of Barbie dolls) — Haynes’ output has concentrated on dramas set in the American past, often infused with a queer sensibility: Los Angeles in the 1920s and ‘30s (Mildred Pierce), the glam rock scene of the 1970s (Velvet Goldmine), the closeted shame of the 1950s, both Douglas Sirk-inspired suburbs (Far from Heaven) and the hushed repression of the city (Carol). Haynes knows it’s a niche for him and one he embraces.

“Even in Safe, which was filmed [and released] in 1995, was set was 1988,” Haynes offers.

In his latest film, Haynes doubles down on his fascination with the past, delivering, in many ways, two films in one. Wonderstruck — one of the truly great films of the year, which opens today — tells two parallel but separate stories. In 1977, when Ben (Oakes Fegley), a deaf 11-year-old boy from the Midwest loses his mother, he sets out for New York City to track down the man he suspects is his father. Meanwhile, in 1927, a deaf girl named Rose (Millicent Simmonds), also heads for NYC to find the silent movie actress (Julianne Moore) with whom she is obsessed. As each child winds their way through the unfamiliar streets, they experience friendship, rejection, fear and discovery in ways that converge unexpectedly.

More than just cross-cutting between stories, Haynes has constructed two distinct universes: 1927 is a tribute to silent films, told wordlessly in black-and-white; 1977 has the gritty realism of a blaxsploitation film. Yet at the center of both is a monolithic building that unites and protects them: The Natural History Museum.

Julianne Moore, right, unifies the two timelines in ‘Wonderstruck,’ one of the year’s top films.

We sat down with the openly gay director to talk about his preoccupation with the imagery of the past, his respect for his audiences and how his long-banned film is getting a second life.

Dallas Voice: One of the aspects of your films that I have always respected is how you never over-explain to your audience — for instance, in Wonderstruck, you start with a quote by Oscar Wilde, but you never identify the quote as his.

Todd Haynes: I assume people will know it, or not — it doesn’t have to be attributed. [I try to] show a high regard for the viewer and [that they might] feel different things at the same time — like in Superstar, to watch dolls tell a story and also have emotional connections to them. I always have a belief that audiences have conflicting thoughts.

Speaking of Superstar, it has only been available underground because you used the music of The Carpenters without permission from Richard Carpenter….

We’re actually doing a restored Superstar

version that will premiere at Sundance [this January]. We’ve been working on it for years now. The print is gorgeous.

Wow, how did you resolve all the legal issues that have blocked it?

We haven’t. None of the legal circumstances have changed. But Sundance is restoring [films that debuted there].

What is your interest in period pieces?

All movies have a frame, but because of the naturalism of the medium, the frame may disappear. Period films offer a kind of frame where the frame is shown to you. It kind of asks the viewer to think about the frame and how it relates to them and their lives and how that informs their [perceptions].

As I was watching Wonderstruck, I was amazed at how this could ever have been a book because it was so visually, so inherently filmic. And then I found out the book was from BrianSelznick, the author of The Invention of Hugo Cabret [made into the film Hugo] and so was filled with drawings…

[In Selznick’s book], the entire 1927 story is told only in drawings, and the 1977 story is told in text with no drawings. And then they join. It was a clear indication of how cinema could be united by all sorts of nonverbal language. [The 1927 scenes] are not carried by dialogue — it was so clear Brian was bitten by the cinematic bug.

It’s compelling how you tell the stories visually, and how different visuals are even while the experiences mirror each

other.

In all of these ways formally, the [periods] keep interacting with each other in point/counterpoint … at times, it’s about each period being the antithesis of each other and playing what on the surface appears to be a forward optimistic era [the 1920s] compared to the [dirt] of the ’70s. But then you think about how adults didn’t know what to do with a deaf child back then, and education for deaf people was not as sophisticated, while the ’70s, for all of its surface problems, was also a period of progressive idealism. NYC is both different and the same — it keeps shimmering back and forth. My editor and I watched a lot of Nic Roeg movies and look on his editing and complex sense of time.

I do love kind of getting into the real textures of the time a film is set in, yet each film is its own kind of idea and experiment and uses the period in a way that is useful. Far from Heaven was the most filmic in the Sirkian melodrama we were employing.

At times I felt that there was this element of magical realism in how all the elements eventually converge.

I didn’t really see that. It’s not a magical realism — it’s rooted in real places and real historical moments. Certainly there are parallels between the two stories — a synchronicity — but actually there’s a logic to it.

Well, perhaps then it’s the aura of time-travel I felt.

There is a sense of destiny and cosmic time — an almost metaphysical time. But it is about how we have survived time and encompassed how we perceive time and how knowledge is contained in little narrative boxes.