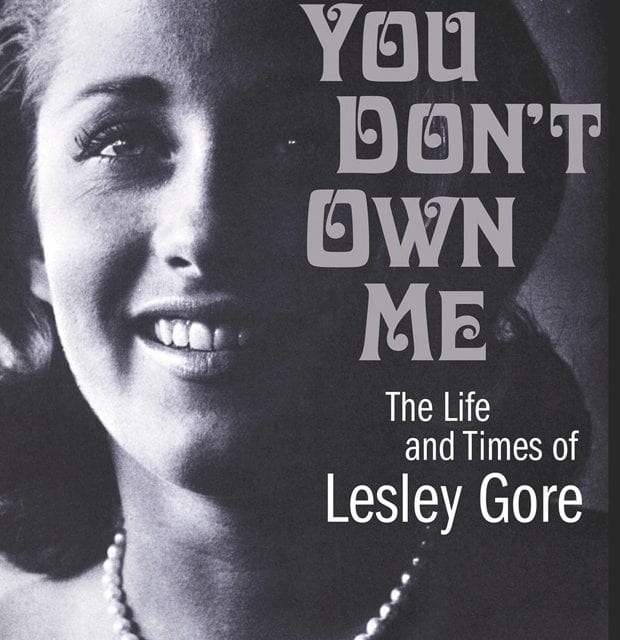

You Don’t Own Me: The Life and Times of Lesley Gore by Trevor Tolliver (Backbeat 2015) $25; 209 pp.

You Don’t Own Me: The Life and Times of Lesley Gore by Trevor Tolliver (Backbeat 2015) $25; 209 pp.

Born into an era of lush crooners and big band swing, Lesley Sue Goldstein was, according to her parents, a musical prodigy. At six months, she could “duplicate the melody of a song;” as a toddler, she loved performing for her parents’ friends.

After joining a girl group in middle school (one that fizzled quickly), Goldstein — who would soon be known the world over as Lesley Gore — entered an all-girl school and sang in a chorus. There, she realized that if she was going to sing professionally, she needed a vocal coach.

Her mother found one, who eventually led Gore to a tiny recording studio where she recorded a few discs for her family. A cousin passed one on to a bandleader, who invited Gore to perform at a gig where the president of Mercury Records was in attendance. In early 1963, he gave Gore’s demo to music producer Quincy Jones and, two months later, at age 16, Gore was a pop music sensation.

But as quickly as her star rose, it began to fall, perhaps because of the Beatles and the British Invasion. Gore’s music continued to hit the charts but, in the end, the new sound and the not-so-innocent times wore away at her popularity. By 1969, Trevor Tolliver writes, “Her career, for all outward appearances, was over.”

And yet, Gore continued to have some professional success until her death about a year ago, with a few minor hits but mostly as a songwriter and in Golden Oldies circles. As for her personal life, she enjoyed a decades-long relationship with another woman, which was something her teenaged self hadn’t dared to do.

When a book starts with a foreword entitled “A Gushing Fanboy,” that’s exactly the tone you’re going to get throughout the book. While it may seem chummy, I couldn’t stop thinking of a supermarket tabloid mixed with discography. The book is overly swooning, breathless and music-industry-driven, consisting largely of reconstructed conversations. I would’ve loved reading more about Gore’s personal life (Tolliver hints at some tumult with her paramour) but instead, we’re plunged back into more about her flagging career. Even that could have been more interesting, were it given a less-chatty spin. Overall, I think there’s an audience for You Don’t Own Me, probably one of ardent fans or behind-the-music folks. For the rest of us, well, you won’t want to own this book, either.

—Terri Schlichenmeyer

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition January 15, 2016.