When LGBT community members report domestic violence, the response is not always helpful

DAVID TAFFET | Senior Staff Writer

When Michael Petsch called the Irving Family Violence Center for help, he was told someone would call him back.

When no one did, he stopped by to ask for some help. He was told no one was available.

Petsch, who was a victim of domestic violence, did what many others don’t do. He sought help. What he found were agencies that deal with domestic violence but were unwilling to help. He found police who showed more respect for his husband’s veteran’s status than for that person’s victim. And he encountered a Dallas County prosecutor who began her case by telling him she never prosecuted “a case like this before.”

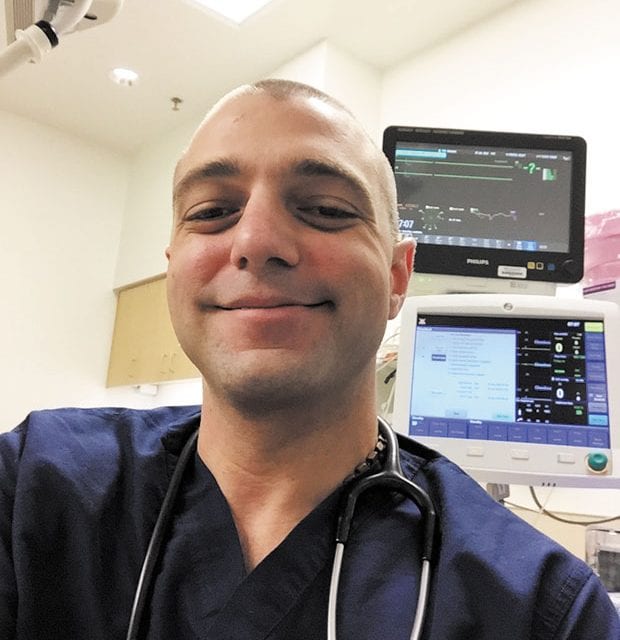

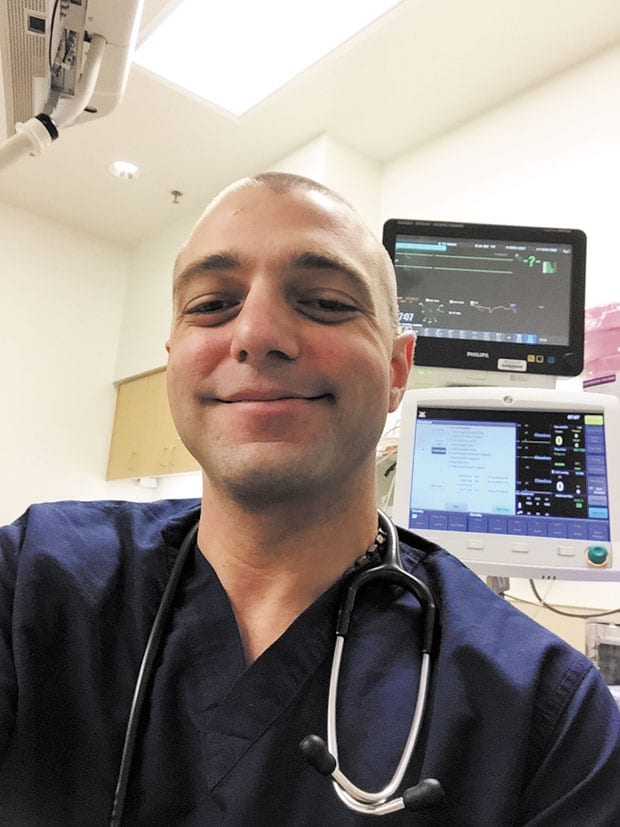

Michael Petsch was the only person able to get an IV started on an infant girl named Brianna when she had to be rushed to the emergency room to be resuscitated. Now, every year on her birthday, her mother brings her to the hospital to see and say thank you again to the nurse Brianna calls her “superhero.”

In 2009, Petsch met his future husband, John, at the hospital in upstate New York where they both worked as nurses. John was in the Army Reserves and had served two tours in Afghanistan: in 2007 as a medic and in 2008 as a nurse.

Petsch said he saw the first signs of PTSD in his husband when they took a trip to the Adirondacks and opened up to each other. As their relationship developed and they spent nights together, Petsch realized his husband was suffering from recurring nightmares.

“He would have night terrors about the Taliban standing over him,” Petsch said, adding that he’d console John, who wouldn’t remember the dream.

“He was hostile at times, but as a nurse I recognized it as a disease,” Petsch said. He said he encouraged John to get counseling, but when his counseling session got to sensitive issues, he’d stop going.

In 2013, Petsch told John he had gotten a great job in Texas and was moving here. John came, too. But since New York had just legalized same-sex marriage, they got married before the move.

Petsch described his husband as someone who would do things for him like warm his towel before a shower on a cold day.

Counselor Dennis Hartzog who works with a number of victims of domestic violence and sits on the Mayor’s Task Force on Domestic Violence said that’s not uncommon. Many people who become batterers are charming. After violence has occurred, they may use that to keep the victim from leaving.

Petsch described some of the counseling sessions he attended with his husband.

He expected violent issues from the war to surface. Instead, John talked about childhood issues — his father beating his mother, staying in a safe house, hiding in a ditch one night. Then he talked about how he hit his sisters when he thought he wasn’t getting the attention he deserved.

John also revealed stories about his Afghanistan experiences — sleeping with one eye open because he was always in fear of an ambush, riding in a convoy when one man in his car was shot and fell on him, dead. He said he was fearful throughout his tours of duty.

John’s motto when he came back was “drive fast and take chances,” Petsch said.

Petsch said John knew how to control him just by raising his voice. He added, “That made me uncomfortable because I didn’t like to fight.” So he would normally try to de-escalate the situation.

One night, Petsch said, he was resting because he was having back pain. Then, “John came into the bedroom, He looked at me weird and said, ‘I want you to know I love you.’”

The next night, Petsch was speaking to his mother on the phone and they got into an argument. John said something about his mother, and “I asked him to stop and he got furious.”

At that point, Petsch said, John jumped on top of him, hitting and choking him. Petsch said he passed out briefly, and when he came to, John was throwing things, hitting one of their dogs with a coffee mug.

Petsch said he tried to call 911, but John smashed the phone on the floor. “I thought he was going to kill me,” he said.

Petsch said he ran into the laundry room to get away from his husband and found his key ring that held a mace sprayer laying on the washing machine. “I told myself this was the end of my marriage,” he said, then he used the mace. John stormed out.

Hartzog said most victims of domestic violence don’t end their relationships after a first attack for a variety of reasons. Many LGBT people are afraid to approach mainstream service organizations for help or they’re afraid of being outed, he said, adding that those with a healthy support network are more likely to leave.

“They have to believe they can make it out there,” Hartzog said.

Petsch said after his husband left, he had some ongoing problems, like someone using a key to break into the house until he got the locks changed. After one break-in, the Irving police officer who responded noticed one of the dogs was acting as if he was injured. Petsch hadn’t noticed that before, but his ribs had been bruised.

The detective assigned to the case, however, wasn’t as sympathetic. Petsch described him as judgmental.

“He made it clear this was a joke to him,” Petsch said. “One day he said to me, ‘If you’re so concerned about it, why don’t you get a divorce, hahaha.’”

This was in 2014, more than a year before marriage equality in Texas. Divorce in the state was being held up by the Texas Supreme Court, which was refusing to rule on a same-sex divorce case.

Petsch said he went up the chain of command in the Irving Police Department with complaints, and the officer who derided him is no longer in the domestic violence division. A supervisor took over Petsch’s case.

While direct contact with his husband stopped, Petsch said he was still being stalked. On a number of occasions, he said, John followed him home at night.

One night, Petsch said John cornered him in his car in the Kroger parking lot on Maple Avenue. When he called 911 for help, the operator told him there were no officers available to respond. Four hours later, he said, police called to ask if he was alright.

Petsch said that was when he hired an investigator to help him.

The case against John went to a grand jury; Petsch said he testified before the grand jury, telling them what he really wanted was for his husband to be required to get the counseling he needed.

Instead, the grand jury recommended that John be charged with attempted murder.

When a month passed without an arrest, Petsch’s investigator went to the hospital where John worked. He explained that a nurse they employed had a felony indictment pending against him. So the hospital suspended John, prompting John to turn himself in to Irving police. But police sent him home, telling him to go home and get his affairs in order, then come back with an attorney. A day or two later, John went through what Petsch described as a “walk-through booking.” And without seeing a judge, John was released on $2,500 bond.

Petsch tried to get a protective order to keep his ex away from him. But while his case met all the criteria to qualify for such an order, Petsch was denied. When he asked the prosecutor why the protective order was denied, she refused to tell him, saying only that she had “never prosecuted one of these cases before.”

At the first hearing, Petsch said, he heard John’s attorney tell the prosecutor — whom he had never met in person — “We need to figure out how to end this quick.” Petsch said she agreed, but when he introduced himself to her a few minutes later, she was quite embarrassed to realize he had heard the conversation.

John’s attorney offered Petsch $1,000 to drop the case. Petsch refused, although, he said, he would have agreed to a deferred adjudication had his husband been required to get the medical help he needed. Such an offer was never made.

In the meantime, the Dallas County District Attorney’s Office subpoenaed Petsch’s medical records for his back condition. They received his entire medical record and uploaded the entire file to the county website — including his birth date, Social Security number and other private information.

Doing so was a clear violation of federal law guaranteeing data privacy and security provisions to safeguard medical information. The fine for willful neglect is $50,000. But the prosecutor’s response: “I’m sorry, that was my secretary’s mistake.”

While that was going on, Petsch began getting notifications that insurance had lapsed and car payments were no longer being made for a VW he and John jointly owned. John had taken the car the night he left, so Petsch had his investigator begin the process of repossessing the car.

When the investigator couldn’t find the car, Petsch told the insurance company he didn’t know where it was. That report got to the prosecutor, who decided that meant the car was stolen. Petsch later got a statement from his insurance company confirming that he never reported the car as stolen, but the prosecutor insisted that the situation make him an unreliable witness.

“You’re interfering with my case,” she told him. Then she dismissed the case.

In his divorce, which became final the past February, Petsch finally did get a protective order from the county, issued by the family court judge.

Better in Dallas

Petsch was fairly new in Texas when his husband attacked him. Despite having little support here, he knew he couldn’t live with violence and ended the relationship as soon as he could. Hartzog said he may have gotten more help if he lived in the city of Dallas, especially from the Dallas Police, whose Family Violence Unit is LGBT-friendly.

The Dallas Mayor’s Task Force on Domestic Violence recommended — and Mayor Mike Rawlings has signed — a resolution that says, “Freedom from domestic violence is a basic human right.”

Five agencies in Dallas offer help to members of the LGBT community caught in situations of domestic violence. (See side bar). Surprisingly, that list includes the Dallas branch of the Salvation Army, which set a national precedent for the organization by reaching out to extend help to same-sex couples and transgender people who need their services.

Less than a year after his divorce was finalized, Petsch is putting his life back together. In 2015, D Magazine named him nurse of the year. He’s still dealing with the financial ramifications of the attack and its aftermath, but he knows he did the right thing by ending the relationship when he did.

Petsch’s advice is to have a safety plan.

“Don’t wait until it’s too late,” he said.

……………………….

Resources for LGBT victims of domestic violence

Families to Freedom

provides transportation to safety

972-885-7020

Genesis Women’s Shelter & Supporters

For people who identify as women

214-946-4357

Hope’s Door

Help’s families, including LGBT, with counseling and shelter

972-422-7233

New Beginning Center

Counseling, case management, legal advocacy

972-274-0057

Salvation Army domestic violence program

Emergency shelter, LGBT welcoming

214-424-7208

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition November 4, 2016.