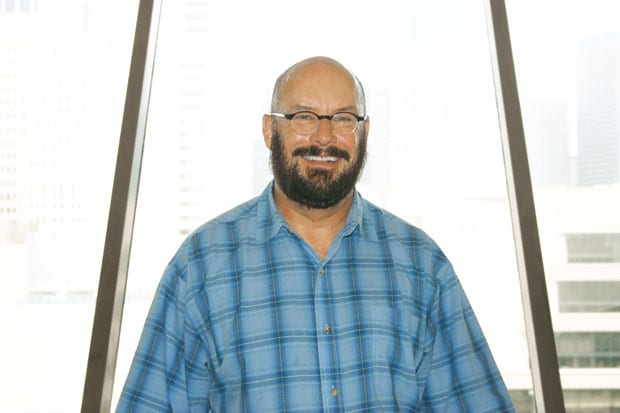

Gay lawyer shares how Dallas has evolved on LGBT issues in 26-year career

BACK TO THE FARM | John Rogers, shown in his office at City Hall, he’s been a Dallas assistant city attorney for 26 years . He will retire to spend time with his husband on their chicken farm in East Texas. (Photo courtesy Anna Waugh)

ANNA WAUGH | Contributing Writer

annamwaugh@gmail.com

John Rogers remembers a time when his sexuality hindered him from working at a Dallas law firm.

After working at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas for a time, he hired a headhunter to help him find another job in law.

He interviewed with a law firm and went through four interview levels with them. The final lunch interview brought all the partners together for one final approval. He was sure of himself going in, as his headhunter told him no one had made it to that point and not received an offer. But when a partner asked if he was married, and he said no, the next question was what neighborhood he lived in. He told them: Oak Lawn.

“And man, that lunch shut down so fast,” Rogers said, adding that they then knew he was gay and he never received an offer from them. “It was very, very obvious that they put two and two together. At the time, if you were an out gay man, you could not get a job at a law firm. It’s still that way in the big law firms.”

He was later told to apply for a position with the city of Dallas. And he was determined to be himself from day one. When Ron Kirk, who would later go on to be mayor, hired him in 1988, he told him he was openly gay and asked if that’d be a problem. It wasn’t.

“His promise has come true,” Rogers recalled. “I have never had any problem with the city being an out gay employee. The rest is history.

I’ve been here for 26 years now.”

But that time is coming to an end. Rogers will retire from the city attorney’s office on June 27.

During his time with the office, Rogers was the first person to successfully prosecute a water pollution case. He developed the investigation procedures to prove the custody of water, knowing that if the city couldn’t prove the reason behind its citations, there was no point writing people up.

He was later promoted to City Hall for litigation and general items, including zoning issues. That’s where he became passionate about the city’s weak, decades-old historical preservation ordinance, which allowed anyone to tear down an old building if the city couldn’t find a buyer within 90 days. His revision of the ordinance went into effect in 2001, when the council approved his changes. It now prevents the demolition of a historical building unless it falls into one of four categories (such as a court-ordered demolition or if it’s in poor, unlivable condition). That remains one of his favorites projects he’s led during his service.

Another is the recent local-option election that turned the whole city wet for restaurants, which he said helped develop South Dallas because grocery stores and restaurants were avoiding the area because it was dry.

Rogers now primarily handles zoning for the city, and he’s done everything in that department from working with the landmark commission and inspection board to the planning committee and City Council.

In the 26 years at the city, Rogers has also witnessed a lot of civil rights developments. He remembers the push to include sexual orientation in the city’s nondiscrimination policy in the 1990s. At the time, the move was controversial, and many employees, while out, were afraid to talk to the press. But not him.

“It was so controversial at the time,” he said. “At that time, there were people who really did not like me talking to the press and did not like me being a gay employee. But then that passed.”

The next step forward for LGBT employees and citizens came in 2002 when City Council passed its citywide nondiscrimination ordinance, preventing bias in housing, employment and public accommodations based on sexual orientation. Gender identity is included in the ordinance’s definition of sexual orientation.

Rogers said the ordinance was “a little bit controversial but not nearly anything like” the city’s policy change years before that. “You could kind of see the world changing a little bit,” he said.

Flash forward to last March, when the council passed its comprehensive equality resolution to study ways in which the city as an employer, advocate and place to live could be a more welcoming place to the LGBT community. Rogers was one of two out employees asked to make recommendations to the council, and he was pleased to see the amount of support for the measure.

“Everybody except for two council members were falling all over themselves to be the champion of that thing, and there was almost no comments from the public about that,” he said. “So it really shows how the world has changed from the 1980s to 2014.”

The level of support for the resolution mirrored the message the city sent out last year with an It Gets Better video featuring a dozen out employees, including Rogers, about their experiences growing up and working for the city, accompanied by comments from the city manger and mayor.

While Rogers will retire later this month, he said he plans to stay involved at some level with the city, including following the pension plan debate. Its Employee Retirement Fund is still debating how to make the municipal pension plans equitable, an issue he quietly mentioned in the past and brought up to ensure it was a focus of the resolution.

Currently, same-sex spouses cannot receive benefits for life if their spouse dies. Instead they are listed as a beneficiary with benefits for only 10 years. Rogers said his husband is still listed as a beneficiary since the plan hasn’t changed yet, and he expects the issue to arise during the debate on the plan’s changes to ensure that retirees can have their same-sex spouses fully recognized.

“They’re going to have to address their married gay employees who are already retired who didn’t get that option,” Rogers said.

Even though the city has offered domestic partner benefits since 2004, the pension system is its own entity with its own board.

But for now he plans to take six months off and spend some time with his husband on their chicken farm in Canton in East Texas, where his husband has lived and cared for the 400 chickens, 200 ducks and 20 geese since they bought the place three years ago.

After that, he’s not sure what he’ll do, saying he’ll reevaluate another job or some volunteer work. As a former board member of the Dallas Gay and Lesbian Alliance in the ‘80s, he said his heart is in the city of Dallas and with its LGBT community.

“I’m hoping I can continue to have some role with the city, not with the city government, but maybe some nonprofit,” Rogers said.

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition June 20, 2014.