After a rough start, ASD has provided housing for thousands

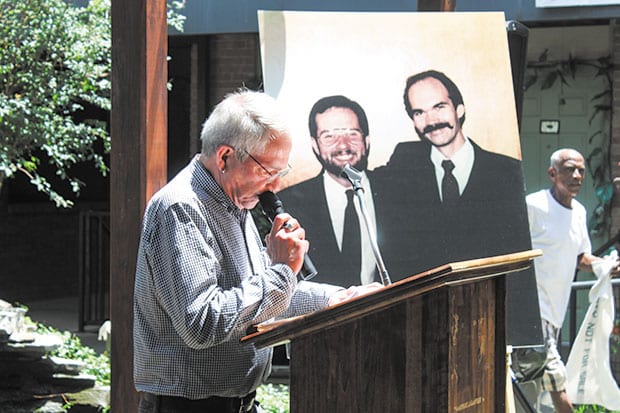

Don Maison, CEO of AIDS Services of Dallas, speaks during a Founders Day event at Revlon Apartments in 2015, as the agency’s founders — Daryl Moore and Michael Merdian — look on from a photo behind him. (David Taffet/Dallas Voice)

DAVID TAFFET | Senior Staff Writer

AIDS Services of Dallas marks its 30th anniversary with its Founders Day commemoration in the garden of Revlon Apartments today (Friday, May 12). CEO Don Maison sat down recently to talk about the agency’s rocky beginnings as ASD prepared to mark this milestone.

ASD started as an employment project. After Phil Gray was diagnosed with AIDS in 1985, he opened Oak Lawn Mail and Message Center — in a space now part of S4 on Cedar Springs Road — where he employed people who had lost their jobs because of health issues related to AIDS or because of discrimination. The project collapsed when Gray committed suicide as his own struggle with the disease became too great for him. But his work to create the PWA Coalition survived.

Under the lead of Mike Merdian, who was already involved in the PWA Coalition, and Daryl Moore, PWA Coalition then became a program of Oak Lawn Counseling Center. They knew housing was an issue for people living with AIDS, so they rented two houses on Nash Street, now known as the Inwood Road entrance to Cathedral of Hope. The houses were approximately where the new Resource Center stands. But after they rented the homes and fixed them up, the landlord evicted them.

Evelyn Petty, who had a real estate investment company in Oak Cliff, heard about what happened and approached Merdian and Moore, arranging to sell them a 22-unit rooming house and hold a lien on the property, Maison said. That property, now known as Ewing House, was the first of four properties now owned by the agency.

Merdian and Moore knew they needed to incorporate the organization, but then things went from bad to worse. The purchase of the property was mostly funded by an anonymous donation of $175,000; then Dallas Voice discovered that the money had been embezzled from First Texas Savings Association by a former branch manager, Patrick Debenport.

Fortunately, as the coalition’s resource director, Mark Rogers, explained to the Voice a few months later, they had reached an agreement and the embezzled money “is now considered a loan. We have a formal note and we’re paying the money back with interest.”

Reports at the time made it sound like the two sides just came together and agreed on amicable terms. In reality though, it took intervention from then-state Sen. Eddie Bernice Johnson to get it done. A nurse before entering politics, Johnson fully understood the need for the facility, and her staff found three attorneys, including Maison, to represent the agency.

PWA Coalition received a grant in 1988 to hire and executive director, and Merdian prompted Maison to apply and the coalition’s board, after considering about 100 applications, offered him the job. The original building, then called A Place for Us and now known as Ewing House, opened as protesters with signs declaring “Keep Oak Cliff Clean and Healthy” and “No gays/AIDS colonies” picketed outside.

One of the protester’s fears, they claimed, was that the coalition’s housing program for people with AIDS would damage their property values. The irony of their protests wasn’t fully apparent to Maison until years later when he was putting together property to build additional housing units: The first lot he acquired for $2,000, the second for $3,000. But getting the third piece of property was tougher.

When his offer was refused, Maison spoke to the property owner, who didn’t know who Maison was, and who pointed to Spencer Gardens, a facility built by ASD for families affected by HIV, to show how much the neighborhood has increased in value. ASD did acquire that last lot, but it cost four times as much as the second lot, and Maison realized he was penalized for his own success in upgrading the area.

ASD acquired the dilapidated Revlon Apartments in 1988, out of foreclosure. But three arson fires at Ewing within five months, causing $220,000 in damage, closed Ewing for 11 months until repairs were completed, delaying the remodeling work at Revlon.

During the darkest days of the AIDS crisis, 25 percent of the money used to operate AIDS agencies came one dollar at a time, often raised by drag shows and other events in the bars. At ASD, supper clubs fed the residents dinner some nights. Mark Shekter’s Meals on the Move, or MOM, delivered lunch. And Petty, the real estate investor who helped them acquire the Ewing property, was there daily, feeding the residents. Residents’ meals, Maison told the Voice at the time, were available at no charge, “as best we can provide them.”

During those dark days, Petty told Maison, “Stick it out. It’ll get better.” When he asked Petty why she was so dedicated to the ASD residents, she explained that her son had committed suicide, and she believed it was because he was gay. When she developed cancer in the early 1990s having no one to care for her, Maison and his staff moved Petty into Revlon for the last few months of her life.

In 1992, ASD applied for a U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development grant to develop Hillcrest House and moved forward with plans to build Spencer. Hillcrest House opened in 1996 and Spencer in 1998. About five years ago, ASD fully paid off its properties.

Residents pay a portion of their income in rent. They’re expected to work if they’re able and to share in community chores, decision-making and responsibilities.

When Ewing opened, residents who had resources paid between $150 and $275 per month. Those who had no other way to pay — which included most residents whose savings were quickly drained by medical bills — relied on what Dallas Voice at the time called “County Welfare,” which provided $200 a month.

When Maison was hired in 1989, ASD had a staff of five, including Mike Anderson, a straight man with nonprofit experience that Merdian hired to be Maison’s assistant director. Maison was annoyed he wasn’t given the opportunity to select his own assistant ,but Merdian convinced Maison to at least meet Anderson.

Maison said he and Anderson met on Cedar Springs Road, and Anderson asked Maison to introduce him to all of the merchants along the strip. That’s when Maison knew he couldn’t have chosen better himself. Anderson retired in 2012 after 23 years at ASD.

“In all that time, we never had a disagreement,” Maison said.

Neither Moore nor Merdian lived to see what became of their early efforts. Both died of complications from AIDS — Moore in 1988 at age 27 and Merdian in 1993 at age 36.

Maison is now CEO of ASD and is the longest-serving executive director of an AIDS agency in the U.S.

One challenge facing the agency today is something the founders never planned for — parking. Holding back tears while thinking of the thousands of residents who have lived at one of the four properties over the years, Maison said now people are living, going back to work — and they need cars. He compared that to his first few years when he struggled to feed everyone and pay the utility bills and lost residents every week to AIDS.

“Some weeks we would lose four or five people,” he said.

This week ASD marks its 30th anniversary with its Founders Day commemoration from 11 a.m.-1 p.m. on May 12 in the Revlon Apartments Courtyard at 720 N. Lancaster Ave.

……………………

Founders Day Awards

• Phil Morrow Memorial Award: Matejek Family Foundation

• Daryl Moore Memorial Award: Jim Apken

• Special Recognition for Outstanding Support: Wayne Thomas, Douglas Cheatham & Mark Hendon, Kansas State University, Rich Perry, Lee Daugherty, Helen Goldenberg, Lori Davidson, Grupo de Oracion, Liz Maverick.

Reporting by Dennis Vercher from 1988-1993 in Dallas Voice contributed to this article

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition May 12, 2017.