Eli Ruhala’s ‘Queer Narcissus’ is on display through July 20

JAMES RUSSELL | Contributing Writer

james.journo@gmail.com

Eli Ruhala — It sounds like “E-lie Roo-ha-la.” Remember this incoming third-year MFA student at TCU, because he is one of the most talented emerging artists in the region.

That’s clear in his show Queer Narcissus currently on display through July 20 at Arts Fort Worth, formerly the Fort Worth Community Arts Center, at 1300 Gendy in the city’s Cultural District.

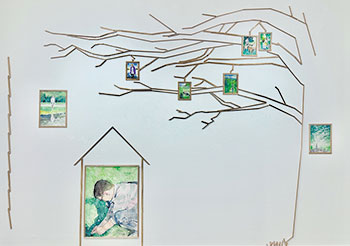

In the autobiographical show, Ruhala uses his core materials of wood and watercolor to create a site-specific work. That’s a catch-all term which arguably could be used to describe ancient engravings in palaces to the Meow Wolf mega experience. Here, Ruhala invites us into his house and reveals — with a bit of trepidation, he admitted — a love story about his current partner and his ex.

In the autobiographical show, Ruhala uses his core materials of wood and watercolor to create a site-specific work. That’s a catch-all term which arguably could be used to describe ancient engravings in palaces to the Meow Wolf mega experience. Here, Ruhala invites us into his house and reveals — with a bit of trepidation, he admitted — a love story about his current partner and his ex.

In previous shows, wood structures and watercolor overlapped throughout the exhibits, such as Momo’s House | Eli Ruhala earlier this year at TCU’s satellite gallery at Moncrief Cancer Institute and Significant Otherness at the Center for Contemporary Arts in Abilene in 2023. The magnificent watercolors are hung and docked along the walls, alongside outlines of midcentury credenzas, what we assume are couches and an awkward rolling office chair.

Queer Narcissus gets its name from Herman Hesse’s novel Narcissus and Goldmund. It’s about an unlikely friendship between Goldmund, a young man who moves into a monastery, and Narcissus, who is a teacher there. They go on different paths: Goldmund doesn’t think he’s fit to a monk; Narcissus is happy with his life. But they later reunite and talk about their lives.

It’s a story about love and journeys.

Ruhala then queers it up less by choice and more by coincidence. He’s been in relationships with men. The topic came to him one night while going through photographs of his ex.

“I felt a part of my life had closed,” he said. And with that closure came change. “They also looked different. I wasn’t directing anymore, but just looking,” he said.

In previous shows, he also toyed with theory in that sort of graduate student shtick where theory overpowers the narrative. Where those works were still commanding, none were as clean as they could have been.

He grew enormously here. It’s why it’s his most intimate, autobiographical and straightforward exhibit yet is also his best.

He speaks about the form and style with clarity, too. Watercolor is one of his favorite media. “You get to see it soak into the paper,” he said. “It’s photo-like.”

And of his approach, he said, “The watercolors show who is in charge. … I’m not composing it. They are,” he said, referring to his partners.

All art tells a story, and when looking at works about identity, we also grab onto our thoughts and choose our favorites. In his words, we’re directing what we see and want to see because we’re in his house.

All art tells a story, and when looking at works about identity, we also grab onto our thoughts and choose our favorites. In his words, we’re directing what we see and want to see because we’re in his house.

One thing Ruhala said he struggles with is growing beyond being a queer artist who makes queer work about queer life. That’s a common concern, though unfair. I mean, is it really “activist” when someone who is not a straight, white and cisgender man creates work that acknowledges, “Hey, I’m here too?”

Plus, we are in his home, with his partners and his sex life and his pop music and his dog. So his queer identity undoubtedly plays a role in how we see the show and where we go. Maybe like any guy with a libido and a thing for quiet scrawny guys, you dash to the nudes — Haring-like portraits of two naked guys, painted from behind, who are looking out the window. Maybe you’re a dog person who dashes to the big brown dogs in bed. Or maybe you have memories of playing in a yard, as seen in the watercolors dangling from tree limbs.

For me, the most jarring experience was something familiar: A tearful figure who is huddled up. If the piece had a name, it’d be “What happened in Las Vegas.”

According to the accompanying text, “Journal’s name: Eli’s call,” he doesn’t know what happened in Vegas.

“New Year’s morning you said it was so wonderful, and it was. I will never forget that morning. Sadly, it’s the last memory I have … the year here really messed with [my memory] really bad. I have many regrets, and you are not one of them. I have never loved so hard as I did with you and never will again.”

When I visited, Ruhala was still setting up the show. He points to a piece on the floor, showing him at Blind Alley Projects, an outdoor gallery in the Cultural District run by Terri Thornton, the former education director at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, and Cam Schoepp, a TCU art professor.

“I’m not sure it fits into the show,” he said.

But then he points to another abstract figure in the background.

“It’s Mitch!” he exclaimed, referring to his current partner. He is the most excited he’s been since we started our tour.

It was a cliché yet fitting conclusion to our tour. Because the show, with its brilliance and beauty, is ultimately a love story where our figure rebounds.

And the best part? He loves someone again.